By the time James West retired from Lucent Technologies in 2001 at the age of 70, his research had won a parcel of awards and a spot in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Most notably, he co-invented the foil electret microphone, which now serves as the model for microphones found in mobile and standard telephones, hearing aids, and video cameras. In 2002, he joined the faculty of Johns Hopkins University as a research professor in the Whiting School of Engineering and was named the school's first chair of the Divisional Diversity Council.

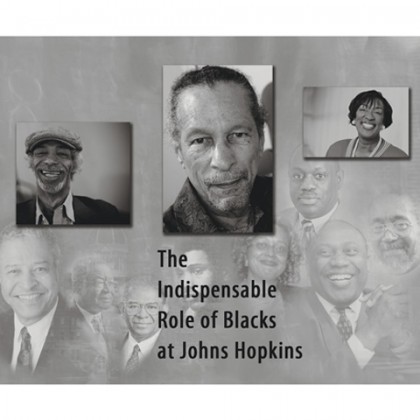

Image caption:The Indispensable Role of Blacks at Johns Hopkins, a traveling exhibition and accompanying website, takes an institution-wide look at black experiences at the university.

West is one of the 37 accomplished individuals included in The Indispensable Role of Blacks at Johns Hopkins exhibition (with accompanying website and booklet) that is traveling around the university's Baltimore campuses. Co-sponsored by university President Ron Daniels, External Affairs and Development, and the Black Faculty and Staff Association (BFSA), Indispensable takes a deep, institution-wide look at black experiences at the university.

The exhibition was inspired in part by a lack of visual acknowledgment of that experience. While touring campus, prospective students and their parents see plenty of portraits of esteemed white alumni and faculty. "One of the parents was with her daughter, who was black, and asked, 'Where are the blacks? You don't have pictures of black people on the wall,'" says Deborah Savage, the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences' IT manager for student technology services. A BFSA member, she served on the Indispensable committee alongside Sharon Morris, a library services manager in the Sheridan Libraries, and Lisette Johnson-Hill, a senior research associate at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. "We never really thought about it like that. So we shared that with the president, and he said we could do something about it."

In 2003, Morris put together an undergraduate independent study project that produced an online exhibition titled The History of African Americans @ Johns Hopkins University. It included a timeline of black history at Johns Hopkins and profiles of significant figures, such as Kelly Miller, the first black student to enroll in 1887. Indispensable builds on that work, not only noting the 1969 establishment of the Black Student Union by Bruce Baker, A&S '71, SAIS '74; John Guess, A&S '71, SAIS Bol '76 (Dipl); and Douglas Miles, A&S '70, but also recognizing, among others, author Wes Moore, A&S '01, epidemiologist Lisa Cooper, and Emmanuel Chambers, a waiter at the Baltimore and Maryland clubs who invested his tips to create a foundation that benefited institutions including Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Peabody Institute.

Johns Hopkins is an institution that is proud of its history, but that history can be diffuse; people can work hard at the same place without knowing what's going on across the hall. "When I first came here there were not very many blacks—as a matter of fact, the only black people I saw were people who cleaned and served food," Savage says. "It was an eye-opener. I'd walk through this campus and never see anybody who looked like me, but they were here."

The ultimate goal is for black achievement to become a more permanent part of the university's visual history. "We are hoping to see pictures on the walls," Savage says. "When students walk through Mason Hall, we want them to see somebody who looks like James West or Ben Carson on the walls. Give them something to aspire to."

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News