A flurry of recent news stories paints a picture of a widespread cheating problem among college and college-bound students nationwide.

- In June, the U.S. Air Force Academy revealed that 78 cadets were suspected of cheating on an online calculus test by using an unauthorized online math program during the exam.

- Harvard College said this summer that more than 100 students in a spring 2012 government lecture class were being investigated for allegedly plagiarizing answers and collaborating inappropriately on the final take-home exam.

- In September, New York's prestigious Stuyvesant High School announced that some 60 students were suspended or facing suspension for using text messaging to cheat on a citywide language exam.

Academic dishonesty is arguably as old as school itself. But what particularly concerns the authors of a new book about college cheating is that many of today's students don't think that behaviors such as plagiarism and collaborating on tests even qualify as cheating at all.

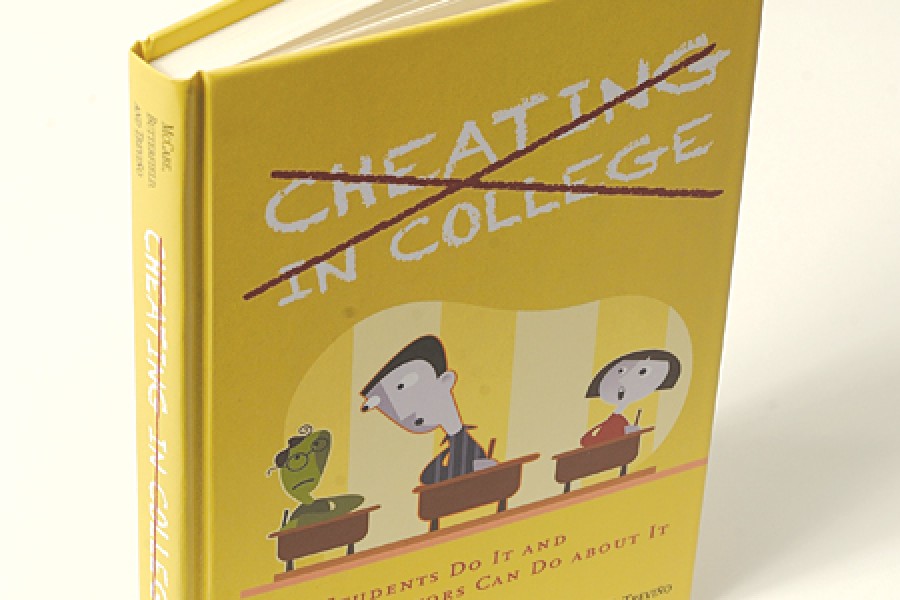

"As long as they think others are cheating, students feel they have no choice but to cheat as well," says Donald L. McCabe, a co-author of Cheating in College: Why Students Do It and What Educators Can Do About It, published in the fall by the Johns Hopkins University Press.

The book, co-authored by Kenneth D. Butterfield and Linda K. Treviño, reflects some 20 years of research led by McCabe, a professor of management and global business at Rutgers Business School. He used a survey he created to gather data about cheating from a quarter of a million high school and college students from some 250 public and private schools across the country.

McCabe became interested in academic integrity as a secondary area of research when he was starting his academic career at Rutgers. He had graduated from Princeton University, which has a strong honor code, and wanted to study how students viewed cheating and other forms of academic dishonesty. Some of his findings include:

- Fewer college students are admitting to engaging in such forms of cheating as copying material in a paper without footnoting it and plagiarizing public materials. The rate of self-reported cheating among college students has decreased over the last decade from 74 percent of students in 1990 to 65 percent in 2010.

- Cheating behaviors are well-established in high school, where student cheating is fueled by pressure to earn good grades, get into college, and please parents. A high school senior commented on the survey, "If you don't get caught, you did the job right."

- Even though the number of students reporting cheating is down from 40 percent in the early 1990s to 15 percent today, McCabe suspects that cheating is still a problem. "Each year I get lower and lower indications of cheating going on, but at the same time I'm getting fewer and fewer students responding to my surveys," he says. "I believe cheating is as much of a problem as it has always been. Students just don't want to talk about it."

To counter cheating, the authors say that educators need to work together with students to build academic integrity on campus by designing a system that supports academic honesty, trust, and accountability.

Many of the tenets of a classic academic honor code, such as student judiciary and reporting, unproctored exams, and having students sign a pledge of honest work, can be a successful part of this system, they say. But it's not enough to simply say you have an honor code if no one practices or enforces it, says co-author Linda K. Treviño, a professor of organizational behavior and ethics at Pennsylvania State University. "What we are trying to do is create a context that supports doing the right thing," she says.

Treviño talks about setting high aspirations for students regarding academic honesty and having shared values and standards. Then if students do cheat, it's important that the accountability system in place is one they've helped create. "Faculty and staff need to be willing to provide guidance and resources but also share power with students," she says. "This is a community effort."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged education