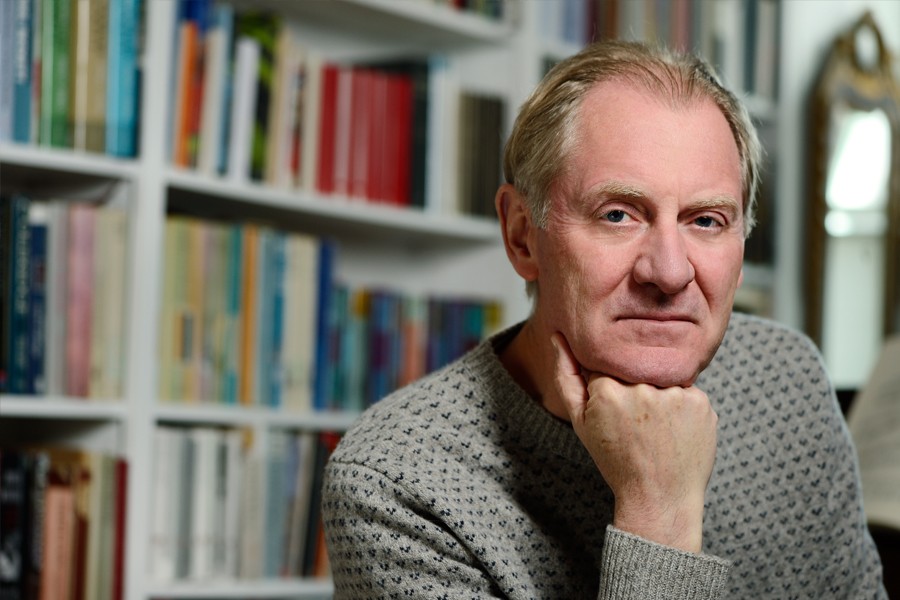

English poet Andrew Motion has been living in a modest state of flux the past few months since moving to Baltimore from London. He joined the Writing Seminars as a Homewood Professor of the Arts in the fall semester, and over the summer, he; his wife, Kyeong-Soo Kim, a translator; and their cat settled into their Baltimore home, which needed a bit of work to fix it up. So they've had contractors around the house for three months, a situation that can be stressful. He's maintained his sanity, he says, by writing. "I can put up with more or less anything provided I have a little place and time to write," Motion says during an interview in his Gilman Hall office. "I can steady myself with that."

He looks forward to discovering what that writing might look and sound like after exposing his ear and mind to American culture and speech. He's already proved himself one of the more versatile authors and critics of English poetry. Motion began publishing his works in the early 1970s, wrote a few collections of critical essays in the 1980s, and by the 1990s was writing duly celebrated biographies of poets, including Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life, published in 1993, and Keats, published in 1997.

Motion was named the poet laureate of the United Kingdom in 1999 after the death of Ted Hughes; Motion occupied the post for a decade, and during that time he partnered with sound engineer Richard Carrington to create The Poetry Archive, an impressive online library of poetry, English-language authors reading their works, and educational tools for the teaching and studying of poetry. Motion can be heard reading his own poetry at his Poetry Archive's author page.

After retiring from the poet laureate position in 2009—he was knighted that year for his services to literature at the Queen's Birthday Honors—Motion took his writing into new territories. In 2012 he published both The Customs House, a reflective, impressionistic collection of war poetry; and Silver, a swashbuckling sequel of sorts to Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, picking up about three decades after the adventure of that late-19th-century novel. This year has seen the release of The New World, a page-turning follow-up to Silver involving its two main characters, and Peace Talks, an arresting new poetry collection. The Hub caught up with Motion to talk about his coming to Johns Hopkins, writing about time's arrow, and how war poetry has changed over the course of the 20th century.

Could you tell me a bit about wanting to come to the U.S. and a university at this point in your career?

I wanted to come here because I was offered a fantastic job with very good students and very nice colleagues, one of whom I knew, [Writing Seminars Co-Chair] Mary Jo Salter, who made me feel like this was going to be a happy home. I thought, too, that if I understood the job right, it might leave me more time to do my own work than I've ever had before. And at 63, that's the sort of thing that you start to mind about. If I die at the same age as my father, I've got 23 years to live. How many books is that? Five? I want to think properly about them.

So there was the job, there was the time, and there was thirdly something to do with that great [T.S.] Eliot phrase about old men needing to be explorers. I'm not quite an old man yet, but I'm not a young man anymore either, and I've seen too many people freeze and diminish in the last third of their lives. I thought to give myself new challenges, new opportunities, new faces, new ways of thinking about things, and to open myself up to the great, strange Niagara roar of American poetry, would be a pretty interesting thing to do.

I know you've been here for just a few months—and I say this only after reading the new book and then going back to read The Customs House—but as you mentioned all the things that come with a new country, that includes new speech patterns and rhythms. How do you think those might impact the way you write? I ask only because the way you write, I wouldn't call it colloquial, but it's very direct. I can hear speech in it.

I hope so. That's certainly always been my ambition. I've said this before I'm afraid, but I've always wanted to write poems that look like a glass of water but turn out to be gin. I want them to look completely simple. I want nothing high art about the poems. I want the plainness that I find, for instance, in Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas, and Philip Larkin. They all create a limpid surface through which you look down into the interesting, complicated world of a life of feeling. That's my ambition.

At the same time, as I say, I also want to get American influences into my head. England never had Whitman. So it never had that big, torrential—when I was speaking about the Niagara roar, I was thinking of Whitman—that open-it-all-up, be brave, risk-a-certain-flatness kind of expansiveness. That's what I want to get in. The size of the country, the size of the American imagination, feels like a license to me. We'll see where it takes me.

I wanted to ask two questions about being poet laureate. I imagine it as being the ambassador for poetry.

Well, it's an honor, and I was pleased to be asked to do it for that reason, but I also wanted to do it for poetry. I wanted to strike a balance between taking poetry very seriously, thinking poetry has a very important role to play in the role of humanity, and at the same time not making it seem that it only existed in ivory towers. To spread the word, but to spread the word without any dumbing down.

The Internet was invented more or less exactly as I took over, and I was also very keen to do something which made use of that for poetry. So that's where the idea of the Poetry Archive came from.

That's the second question I wanted to ask—the Poetry Archive is a very smart use of the Web. And for me, I'm 45, a product of American public education in the 1970s and '80s, and growing up, poetry to me felt stand-off-ish and, well, posh. It wasn't until I got older that I realized how incorrect my understanding was. So providing that kind of access to the wide range of poetry to anybody with Internet access feels smart.

I'm proud of it. My friend Richard Carrington, whom I set it up with, and I both thought that it would be valuable and useful when we launched it about 10 years ago. But even we had no idea how popular it would prove to be. We now have 300,000 people a month using it, and every month they listen to nearly 2 million pages of poetry. Extraordinary. All those articles one sees in the newspaper about how nobody reads poetry anymore—well, they don't buy books in very large quantities; that is true. But the Internet has been a very good friend to poetry. In fact, you can accurately say there are more people reading poetry now than ever before in the history of the human race.

And I think that for a lot of people, having the opportunity to hear the poet read is profound—it opens a door that you might not have thought about before.

Absolutely. Earlier you were talking about tone of voice in my poems. The thing I didn't say then, but might have done, is that I pay particular attention to how poems convey their meaning as much by the noise they make as they do by what the words mean when we see them written down on the page. Poetry has as much to do with acoustics as it does with definitions. Sound itself is an emotionally charged thing, even if it doesn't "mean" anything. Think about the word "nonsense," which in ordinary discourse means rubbish, to put it politely. But if you put it next to the word "poetry," it doesn't. Nonsense poetry is not rubbish; it's Lewis Carroll. It's transmission by sound effects, which can be rather nebulous but nevertheless has meaning. None of this would be new, of course, to a person sitting in a mead hall in the year 900. They would get it completely. But since the invention of the book, much as I love books, the printed page has tended to sideline the acoustic existence of poems. And we've helped re-establish that.

Let's talk a bit about Peace Talks. I have to confess that I'm not the most well-read poetry reader, and what first came to mind when I saw the title was, well, the Dayton Accords, a discussion that happens after a conflict of some sort. But after reading it, I get the sense that it's talking about a different kind of peace in some ways, that relationship between a human life and its own environment in place and time. What really placed that idea in my mind is an early poem in the book, "An Echidna for Chris Wallace-Crabbe," and the line, "He had no idea/ anyone is waiting for him at the end of history." Are there any loose thematic ideas running through the collection itself?

I think so. As you have gathered, the poems in the second part of the book are poems about men fighting in 20th-century Western wars. Why did I get interested in writing those? I don't entirely know. My dad, as you may have gathered from one or two of the poems, was a soldier for a large part of his life. He fought in the Second World War and then stayed on in the army afterward. So all of my early memories of him are him in uniform. I didn't start writing these poems until he died, and with retrospect, I think I may be elegizing him even when not writing about him directly.

Which brings us to the earlier part of the book, which contains poems that in one way or another are about living in time. They're about being a member of the only species that knows that its days are numbered. I look at my cat, who came from England with us, and she knows about time in the sense that she knows that she gets hungry. But she doesn't know that she's going to die, as you and I do.

You explore mortality in different ways. For instance, in "The Realms of Gold," about a writer working on a biography of another poet, D.J. Enright, and the line, "who am I to let it vanish completely/ without returning an echo," which touches on the fact that after you pass, there's a good chance nobody hears.

I'm glad you pulled out that poem. D.J. Enright was somebody that I didn't actually know terribly well. I worked with him for a bit. He's a good example of a good minor poet, an immensely learned man, who did all that work on Proust to an incredibly high standard, who traveled a lot, who led a really interesting life. And then he died, and who reads him anymore? Who cares? So, yes, it's an elegy for minor poets, which is all of us. I mean, how many great poets are there? About six—there's Milton, there's Wordsworth, there's John Keats. Everybody else is just doing the best they can.

I appreciate how that poem touches on how we remember things as humans and as societies in collected papers and archives, which you also explore in the poem "In the Stacks," in the section that begins "This report is a continuation of one numbered 303A," and throughout you include the bracketed "[words missing here]" when a part of the report was redacted. Could you talk a bit about working with pre-existing sources to write contemporary poems that are about the past?

I've done a lot of that, and I'm very interested in the ways a text that I make can incorporate things that other people have done—using it, as that poem does, as the platform for jumping off, for reshaping. I think of these things really as collaborations. All poetry is a collaboration to a greater or lesser extent. There has to be a presiding intelligence and imagination which makes it my thing or your thing or whatever. But the text itself is much more of a team effort than people are generally prepared to admit. And I want to make a virtue of that.

Tell me a bit about the title poem, "Peace Talks." I gathered from the acknowledgments that it was a piece originally made for BBC Radio 4, so given that acoustics are part of the poem, did it change at all when it came time to set it on the page?

It did. But first let me say this. The last British troops were about to come home from Afghanistan, and I wrote to the BBC and said that I wanted to go and interview them, and use these interviews as the basis for poems. The BBC were interested in this, so they assigned me a producer, and we flew to Hanover, to a camp about 40K north of Hanover, at a place called Bad Fallingbostel. The arrangements all had to be done through the Ministry of Defence, and they decided that I should go there. So we flew to Hanover, got into an army car, and drove up the autobahn. About halfway along this road, I realized I was going exactly the way my father had been during the war. My father landed in Normandy, fought through France, and then swerved northeast toward Poland. The reason I knew was because we went past Belsen, the concentration camp. My father never talked about the war, but I remember him telling me about that. He didn't actually liberate it, but he went past it. How did you know, Dad? I asked him. Because I smelt it, he said. I never forgot that. So my whole time in Germany was weirdly charged by memories of him. He was tremendously with me.

Anyway, we got there, I talked to the guys, they were completely fascinating. They were big, burly, nothing-hurts-me, water-off-a-duck's-back sort of people. The plan was to record our conversations, bring back the tapes, then somebody at the BBC would type them out and I would go through the transcripts with a Geiger counter, looking for poems, and write them out. I realized within five minutes that it wasn't going to be like that because the people I spoke to were pretty inarticulate. Most of them had left school very early. They were sparsely educated. Furthermore, the army doesn't want soldiers to be super articulate about what they're doing. They want guys who get up and do the job. The army drills out of its men the stuff that I was looking for.

In the end, therefore, I found myself looking not for episodes of extraordinary poetic articulacy but for the opposite—for very deep, complicated things being expressed in language that was not up to it. That little poem called "One Tourniquet," where the boy gets his legs blown off—the woman who told that story, she was wonderful and clearly extremely good at her job, but she'd seen something that had evidently traumatized her and she didn't want to, or wasn't able to, admit how traumatized she was. I tried to write a poem that made a virtue of that. A poem that was supersimple.

It's interesting to hear you talk about this process and think about what you said earlier about writing poems that look like a glass of water but are actually gin because in these groups of poems the most devastating lines are the ones that are the most seemingly innocuous. In "The Program," where the young guy in military intelligence says, "I'm 20," an age when you don't know anything and he's already having to deal with so much. Or in "Critical Care," where the medic announces "his foot still has a pulse"—it's a simple statement of fact, but in the context of what's going on, it's world-ending.

That was certainly my intention. It was an extraordinarily powerful week for me, one of the most intense of my life. Because it did well on the radio and won a big prize[ the 2015 Ted Hughes award], the BBC were keen for me to do something else in the same sort of way. So I'm about to go out with the same person to try and write something about environmental matters. It won't have quite the same explosive kick as the war poems, but I'd like to talk to people who are at the front lines of environmental work, bird men and people who are seeing species' numbers plummet. We're doing that next spring.

I wanted to ask you one last thing, and it just occurred to me while we've been talking: War poetry is a genre, for lack of a better term, that we know, and, as you mentioned, men for no small part of the 20th century didn't go to university, they went to war. Over the 20th century, there's a different level of education seen in the men who went to World War I and the ones we send into battle today. How have the wars of the 20th century changed the nature of this poetry?

That's a very interesting question. One of the courses I've been teaching is a course on the elegy. We had several sessions in the middle of the term talking about war poetry, particularly about the First World War, Wilfred Owen, and so on. First World War poetry has a peculiar intimacy about it. Men's bodies, hand-to-hand fighting, the enemy is not very far away. "I am the enemy you killed, my friend," says that spook in Owen's poem "Strange Meeting." "I parried; but my hands were loath and cold."

By the time you get to the Second World War, the nature of conflict has changed in ways that often mean that men are encountering each other in comparatively remote settings. So Keith Douglas, the great British poet of the Second World War, who was killed at Normandy in 1944 but had previously fought in North Africa, at [El] Alamein, says in one of his poems, "Now in my dial of glass appears the soldier who is going to die." In other words, he's looking at him through a rifle scope. This, in a shorthand way, manifests the differences.

Tagged writing seminars, poetry, faculty