Nearly two years deep into his research, Professor Stuart "Bill" Leslie has uncovered a number of "what if?" moments along the lifespan of Johns Hopkins University.

What if the university had developed at Johns Hopkins' summer estate at Clifton Mansion instead of at Homewood? What if the football team had accepted an offer to play in the Tangerine Bowl in 1948? What if the university had followed through with creating a law school?

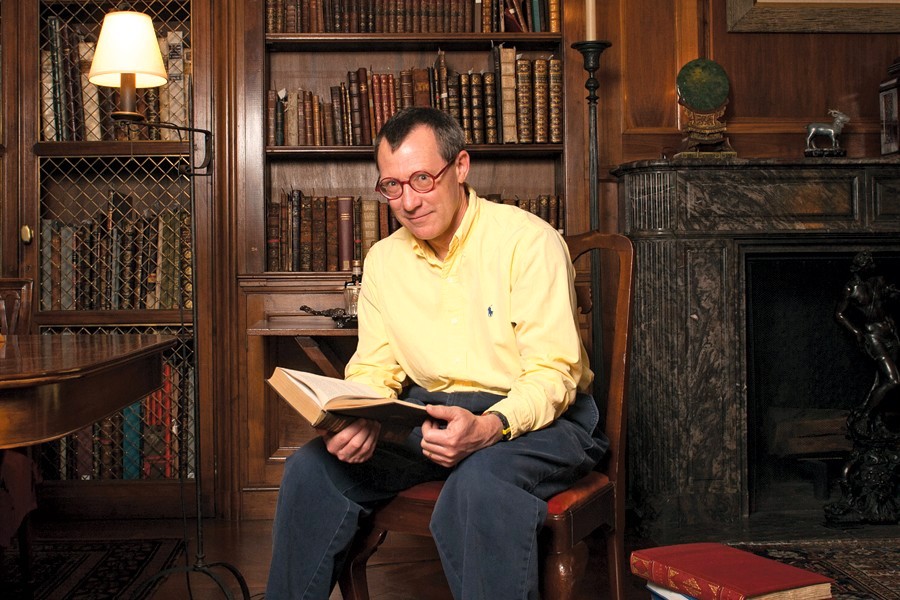

Leslie, a longtime professor in the Krieger School's History of Science and Technology Department, has been digging through archives since summer 2013, after he was commissioned to write the definitive history of Johns Hopkins University. His book, projected for completion in 2018, will cover all divisions of the university, from its founding in 1876 to its present administration. In 2013, the Office of the President also launched Hopkins Retrospective, a project—with Leslie's book as its centerpiece—exploring new ways to share the university's history within the school community and in Greater Baltimore.

On Friday, as part of Alumni Weekend, Leslie will pause from his research to give a lecture on "The Hopkins That Might Have Been." The talk is scheduled to begin at 4 p.m. in Hodson Hall.

The alternate narratives that could have shaped Hopkins—both missed opportunities and avoided mistakes—have been spinning constantly through Leslie's head during his research.

Recently, he's been looking at the Chesapeake Bay Institute, a research center the U.S. Navy launched with Hopkins in 1947. Eventually Johns Hopkins used the institute for oceanography and estuarine science.

But "it got caught up in internal politics and ran out of money," Leslie says, so the university administration abandoned the institute in the early 1990s. With that, he sees a lost opportunity. "We gave up an opportunity to be an authoritative voice on environmental issues in the bay"—an East Coast rival to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Likewise, Leslie believes "something was lost" in Hopkins' failed plans to develop a pioneering undergraduate program exclusively for juniors and seniors. The idea was for upperclassmen to transfer to Hopkins from other universities, gearing themselves toward graduate studies.

"We tried it in the '20s, tried it in the '50s … but we never were able to pull off that idea of a unique undergraduate experience, something distinctively Hopkins," Leslie says.

Strong personalities have also demanded Leslie's attention, like Broadus Mitchell, a rabble-rouser on the faculty in the 1920s and '30s. The outspoken socialist ultimately resigned over the university's refusal to admit an African-American student into the graduate school.

"We don't have enough radicals like that," says Leslie.

Among the materials he's unearthed on Mitchell is a blue book the professor deliberately saved to defend himself to the administration. After a student's parent complained about Mitchell's controversial statements in class (such as calling the Supreme Court justices "nine old bastards"), the professor held onto that student's final exam to prove he wasn't giving an F out of mere spite. He wrote on the blue book: "This is the worst final exam I ever saw."

Leslie's research has involved combing through the archives not only of the medical campus and Homewood but also places like the Rockefeller Foundation, or the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia to sort through the papers of archaeologist and biblical scholar William F. Albright.

Part of his process —which he says is "part serendipity, part intentional"—involves pursuing stray items of interest down the rabbit hole until they tell a full story. "You find a lead, something you didn't know about, and you follow that as far as you can," he says.

Leslie, who joined JHU in 1981 as a postdoctoral fellow, hasn't yet started writing his tome, but he's come up with an organizational structure. He's arranging the book based on seven major "places" —such as the Clinic, the Laboratory, Community Spaces, and the Field.

Within that framework, he'll follow major events and figures chronologically, aiming to focus on significant personalities. "The challenge of all the chapters is to bring the personalities to life in the space," he says.

Leslie's lecture on "The Hopkins That Might Have Been" takes place Friday, April 17, from 4 to 6:30 p.m., Hodson Hall, Room 310. To register to attend this lecture, please visit http://bit.ly/hopkinsretrospective. The event also will be shown live on the Johns Hopkins Ustream channel. Following the lecture, Hopkins Retrospective will host a reception.

Posted in University News

Tagged university history, hopkins retrospective, bill leslie