Editor's note: This article will be published in the forthcoming March/April issue of the Gazette.

The answer to the world's biggest problems doesn't lie in any one discipline, be it biology or public health, sociology or medicine. Rather, big problems require big thinkers, people who bring the best insights from a wide spectrum of human knowledge.

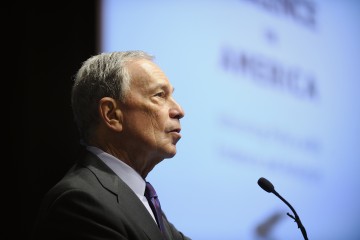

Bridging disciplines and training a new generation of cross-specialty collaborators are the goals of Johns Hopkins' new Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships, funded a year ago by alumnus Michael R. Bloomberg, class of 1964. Over the next five years, 50 world-class scholars will be appointed to the professorships; each will be a part of two or more schools and divisions, conduct interdisciplinary research aligned with the university's signature initiatives, and teach undergraduates as well as other students across the university.

As President Ronald J. Daniels and Provost Robert C. Lieberman wrote in a recent campuswide email announcing the first three BDP appointments, "This university is committed, as much or more than any other, to assembling experts from divergent disciplines to attack humanity's most important problems from every angle."

Appointing the first three scholars to these prestigious endowed chairs, says Barbara Landau, vice provost for faculty affairs, is the first step "to putting in place very, very distinguished faculty whose passion, their work, their teaching all revolve around problems that can be solved by bringing together a variety of disciplines."

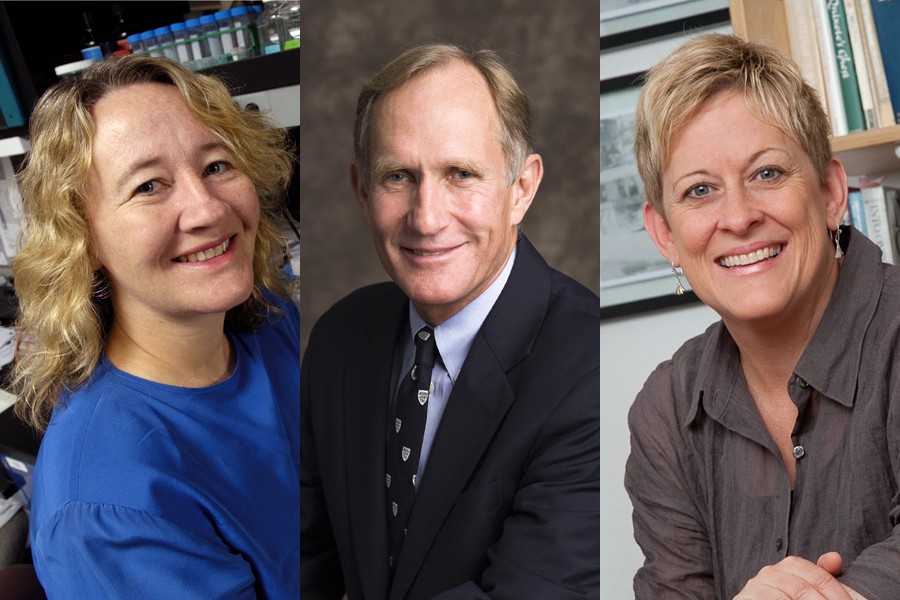

The first crop of BDPs includes two Nobel laureates at Johns Hopkins, Peter Agre and Carol Greider; and world-renowned sociologist Kathryn Edin, a former Harvard professor who joined the Johns Hopkins faculty in January and has an ongoing Baltimore-based program of research.

Kathryn Edin

Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, Department of Sociology

Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health

As one of the nation's leading poverty researchers, sociologist Kathryn Edin provides a glimpse into low-income America: How do single mothers survive on welfare, and why don't more of them work? Where are the fathers, and why do they disengage from their children's lives? Can their lives change as a result of welfare reform? Edin comes to Johns Hopkins from Harvard University—where she was a professor of public policy and chair of the Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy—for a Bloomberg Distinguished Professorship that spans the disciplines of sociology and public health.

The two disciplines may seem disparate, but according to Katherine Newman, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, "the field of public health always involved sociology because it's looking at antecedent conditions that lead to health issues: households, family structure, race inequalities … all of that contributes to inequality in health outcomes."

Edin, who moved to Baltimore in August and in February was named a fellow of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, has already made a splash in Washington, D.C., anti-poverty policy circles: Since assuming her position at Hopkins on Jan. 1, she's briefed the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, met with the President's Council of Economic Advisers, spoken to Rep. Nancy Pelosi's staff, and had dinner with Sen. Elizabeth Warren to talk about family policy. But despite the time she's spent in D.C., she's ready to make her new home in Baltimore and at Johns Hopkins.

She's already been conducting research here since the 1990s, collaborating with Stefanie DeLuca, an associate professor of sociology, on a major project to study intergenerational poverty among Baltimore's African-American young adults. They started two decades ago, following the families of 150 children under the age of 7 as they grew up in the inner city. Now these children are young adults. "Some now fit the stereotype of The Wire. The surprise is that most do not. Many are trying to make it in the way that we want them to make it: get jobs, support families, avoid welfare," she says. "A striking number strive to be conventional, just like kids in the suburbs. They have very much the same aspirations."

It's a neat tie-in to her work at Hopkins, which includes taking a lead role in the university's Institute for the American City, a new cross-disciplinary initiative designed to tackle the world's most pressing urban problems. "There's so much happening at Hopkins," she says. "The Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships can bring vital new talent to an already world-class university. And Baltimore is a wonderful city for researchers like me, who are committed to finding solutions to some of the most morally urgent social problems of our time. For all these years, I've been doing research and getting ideas about what might work to make the lives of the poor better. Baltimore is a great place to put wheels on those ideas and see how they work.

Carol Greider

School of Medicine, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics

Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology

Johns Hopkins Professor Carol Greider is famous for her discovery of telomerase, an enzyme that protects the end of a chromosome and thereby safeguards the genetic data that make us who we are. For this finding she was named co-recipient of the 2009 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Her success stemmed from a young biochemist's curiosity—she was still a grad student at the University of California, Berkeley, at the time—and her discovery has gone on to form the basis for studying clinical applications to combat diseases such as cancer and dyskeratosis congenita.

It's this connection between basic science and clinical application that most excites Greider, currently the Daniel Nathans Professor and Director of the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics in the School of Medicine, about the Bloomberg Distinguished Professorship. In bridging the disciplines of biology and medicine, she hopes to help her students see how "a primary, basic understanding of cells really does drive innovation in terms of human disease. They'll be able to participate in the research that's involved, to do in a lab as opposed to in a book," says Greider, who will participate in the university's Individualized Health Initiative.

The learn-by-doing technique—recently brought to the Homewood campus in the form of a "flipped classroom" where students learn from recorded lectures on their own time and instructor-led problem-solving during class time—has Greider looking forward to teaching undergraduate students in the Biology Department. "This gives me the opportunity to participate more firsthand in those changes happening at the undergraduate level on the Homewood campus," she says, and she's already planning to take what she learns and apply it to her graduate-level courses at the medical school.

"I'm excited, especially since I already have ties to the Biology Department," says Greider, who has been an adviser to that department for more than two years. "I'll be able to bring more of that basic science to undergrads, have more interaction with them. And I'll be able to expand the circle of people I interact with. It's an exciting time to be in education."

Peter Agre

Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

School of Medicine, Departments of Biological Chemistry and Medicine

For Peter Agre, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology in the Bloomberg School of Public Health, cross-disciplinary research is inherent to the Johns Hopkins experience. Ever since he arrived in 1970 for his first year in medical school and earned his research chops in the Cholera Research Laboratory on the Bayview campus and in the Department of Pharmacology on the basic science campus in East Baltimore, "I felt from the start that I was sort of free to go to whatever part of Johns Hopkins things would take me to in terms of research."

His early career led him to follow Johns Hopkins professors to Case Western Reserve University (for his medical residency) and to the University of North Carolina (for a hematology fellowship), but he returned to Hopkins in 1981 as a research associate in the School of Medicine's Department of Cell Biology; by 1984, he was recruited as an assistant professor of hematology in the Department of Medicine. When you listen to the story of his early-career department hopping, "you might think Agre has attention deficit disorder," he jokes, but his cross-disciplinary curiosity has reaped big rewards, including being co-recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in chemistry for discovering aquaporins, the membrane proteins that transport water into and out of cells. The Nobel came while Agre was a professor in the departments of Biological Chemistry and Medicine and worked with William Guggino, a professor of physiology.

Since 2008, he's continued bridging disciplines as the director of the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute. Though the institute's center is located in the Bloomberg School of Public Health, "we have malaria scientists throughout Johns Hopkins University, including the Homewood campus, the School of Medicine, and even in Africa," says Agre, citing examples from Chemistry, Biology, Medicine, and Public Health. "Our research ranges from mosquito biology to drug and vaccine development to epidemiology to field studies in Zimbabwe and Zambia."

As a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, he will play a key role in the university's Global Health Initiative.

How does he feel about being named to his new position? Referring to his recent 65th birthday and the birth of his first grandchild, Agre reacts, "Slowing down? I prefer to think that I am refocusing. I'm enthusiastic about cross-boundary research activities and try to do the best I can. Moreover, mentoring bright young scholars from throughout Johns Hopkins University is a joy and a privilege. Advocating for Johns Hopkins researchers at national and international levels is something in which I take great pride. I'm definitely a happy camper."

Future Academic Fusion

The appointments are the first of 50 Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships to be established throughout the university within the next five years.

The implications are enormous, both in terms of the collaborative research synergy and the cadre of future students who will be trained in a variety of approaches, from a wide array of disciplines, to solve some of the world's most complex problems in areas such as individualized medicine, the science of learning, and global health.

Finding these solutions requires expertise that doesn't just come from a single discipline, says Landau. "You can't just be an educator. You can't just be a brain scientist. You can't just be a policy person. You have to have expertise in multiple fields," she says.

Provost Lieberman agrees, and thinks that the university is well on its way: "There is already a tremendous spirit of collaboration at Hopkins. That is one of our hallmarks," he says. "I think this program institutionalizes it all in a way that nothing else could."