When Louisa replays the pitch-black moments of the night her father fell from a granite breakwater and drowned, she relies mostly on her sense of sound. Or, rather, its absence. She remembers, amid the confusion and terror, his dropped flashlight landing "almost noiselessly in sand." No splash on the water, no metallic clatter on the stone. Only that the flashlight landed almost noiselessly.

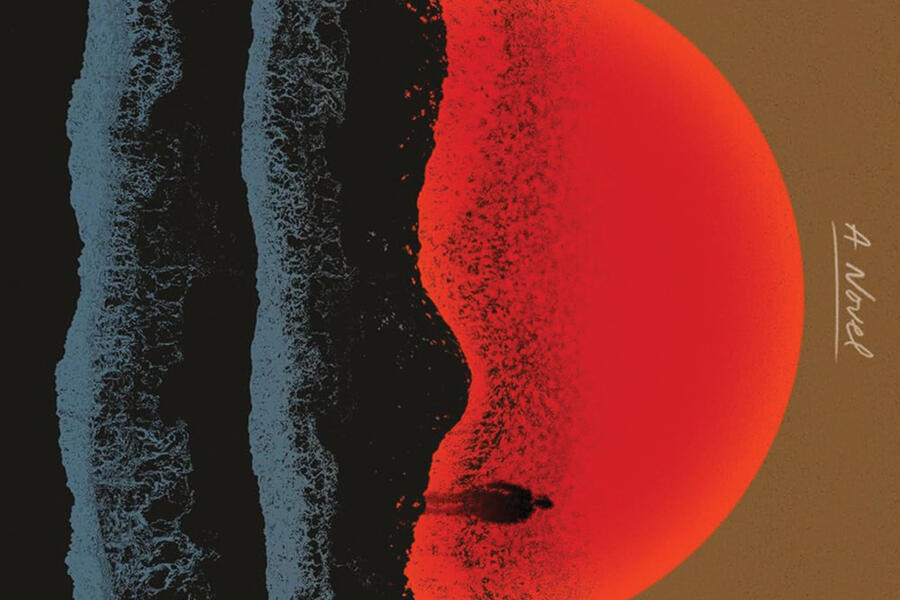

Early on in her latest novel, Susan Choi, a professor in the Writing Seminars, repeats the phrase five times, in quick succession. She's even named the book Flashlight (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, June 2025). But the curious incident of its muffled tumble serves merely as a jumping-off point for a bigger mystery—what actually happened to Louisa's father that evening?—and its tragic reverberations. "The flashlight is just a little signal that maybe something was amiss; it's that nagging thing that lurks in the background," Choi says in a phone interview. "Louisa has a deep intuition of there being something else, but she doesn't really know. And no one else was there. The flashlight started seeming like a good metaphor: It picks out what's hard to see."

Choi's sixth novel follows Trust Exercise (2019), which was awarded the National Book Award for fiction. Set in a performing arts high school, that book explored memory and shifting perspectives. Her American Woman (2003), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, drew on the Patty Hearst kidnapping. "The impulse to steal a human being and forcibly remove them from their environment is a form of violence that's compelling to investigate," Choi says. "I've also always been fascinated by captivity narratives, too—the idea of an abductee being irresistibly drawn on some level to the kidnapper." In her other novels, The Foreign Student (1998), A Person of Interest (2008), and My Education (2013), Choi, the child of a Korean immigrant father and American mother, sifts through notions of identity.

These themes also weave through Flashlight, whose pivotal events occur during the late 1970s, a time when Choi's father, a math professor at Indiana University, briefly relocated the family to Japan for a stint as a visiting professor. Choi, who says she always felt like an outsider in her predominantly white school, had previously never traveled out of the country or even much out of her home state. "We spent about half a year in Tenri, a small city not far from Osaka," Choi says. "I went to a local elementary school and it was a life-changing period. I both blended in and never blended in."

That potent experience, says Choi, was the kernel for the new book and the story of Louisa, a similarly disoriented tween whose professor father, a Japanese-born Korean, brings her and her American mother to Japan in 1978. As Choi began researching what was happening in that time and place, though, she came across a bizarre sliver of history. An unknown number of ordinary Japanese people had, one by one, suddenly vanished from their coastal hometowns, never to be heard from again. "These disappearances were taking place on a very local level; they were private catastrophes that affected individual families," Choi says. "We were in Japan then, but we never knew anything about them."

"The geopolitics of all of this interested me," Choi observes. "But I was uncertain about inflicting these tragedies on the family in the book because truth is stranger than fiction. I found this all irresistible as novel material, but were readers going to say, Oh, come on!?"

As Choi delved into the disappearances—reading "as many survivor accounts as I could bear," along with classics on the topic like the 2013 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Orphan Master's Son by Adam Johnson—the story (and its characters) started spinning in different directions. "I'd say, 'Oh, no, now I have to do more research. I didn't know I was going to end up here,'" Choi says.

While she did eventually travel back to the Japanese town where she lived as a child, she did so only after a first draft of the book was finished. "There's always the danger of letting the research impose itself too much and overwhelm the story, which has to evolve freely," Choi says. "It's necessary, but it has to recede. I need a lot of space for the story to figure itself out."

Posted in Arts+Culture