When the West Indian manatee first earned endangered species protection in the early 1970s, the gentle and sociable marine mammals were critically close to extinction, with only a few hundred of the Florida subspecies remaining on the East Coast. By 1991, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service first began aerial surveillance, they counted just 1,261 Florida manatees. The primary cause of death was boat strikes, which by the late 1990s were killing more than 100 manatees a year.

Image caption: Eric Glitzenstein

Image credit: Harvard Law School

That was when attorney Eric Glitzenstein entered the picture, winning a landmark 2001 case requiring the federal government to expand the species' protected habitat and adopt regulations restricting the construction of new docks and marinas, especially in shallower inland waterways. "There were photos of manatees that had nine or 10 scars on their backs from boats and propellers, and those are the ones that survived. So, we had some pretty visually compelling evidence," says Glitzenstein, A&S '78. Many lawsuits followed over the ensuing years, resulting in additional boat restrictions, expanded protected habitat, water quality protections, and more.

But fast-forward to today, and the species is once again under siege as climate change and human population growth wreak havoc on the manatees' very specialized habitat. More than 2,000 manatees died between 2020 and 2022 when the seagrass beds they depend on for food were destroyed as a result of red tide.

"It was a major massive starvation, and it came as a result of long-standing neglect," says aquatic biologist Patrick Rose, executive director of the Save the Manatee Club. Describing how failing septic systems, improperly treated wastewater, and fertilizer runoff contributed to the harmful algae growth, he says: "The algae blooms were so severe and substantial that they literally shaded out the sea grass and denied it the ability to photosynthesize. And the sad part is that it was all preventable because had they been dealing with the human-caused pollutant problems, we would never have reached that kind of crisis."

The starvation was such that in some areas advocates resorted to artificial feeding, dropping cabbage from riverbanks and boats. While the die-off abated in the past two years, the long-term effects of starvation can be seen in the deaths of 148 manatee calves in 2024, which scientists attribute to the health impacts of prolonged starvation on their mothers.

And so the battle continues, with numerous lawsuits making their way through the courts, including one challenging the Fish and Wildlife Service's controversial 2017 decision to downlist the manatee from endangered to threatened.

A bright spot occurred in September 2024 when the Center for Biological Diversity and allies announced an agreement with the Fish and Wildlife Service to expand the area designated as critical manatee habitat to 1.9 million acres, nearly doubling it in size.

Decades-long conservation battles like the one to save the manatees take exhaustive legal advocacy and persistence in the face of defeat, and Glitzenstein's 40-year career has seen plenty of both. First as co-founder of Meyer & Glitzenstein, one of the country's first and most prominent public interest law practices specializing in environmental conservation, and more recently as director of litigation at the Center for Biological Diversity, he's played a pivotal role in establishing federal protection for hundreds of threatened species. In the process, his trailblazing strategies and tactics have strengthened laws and extended the reach of environmental legislation, expanding protections for biological diversity in all its forms and influencing a generation of environmental lawyers.

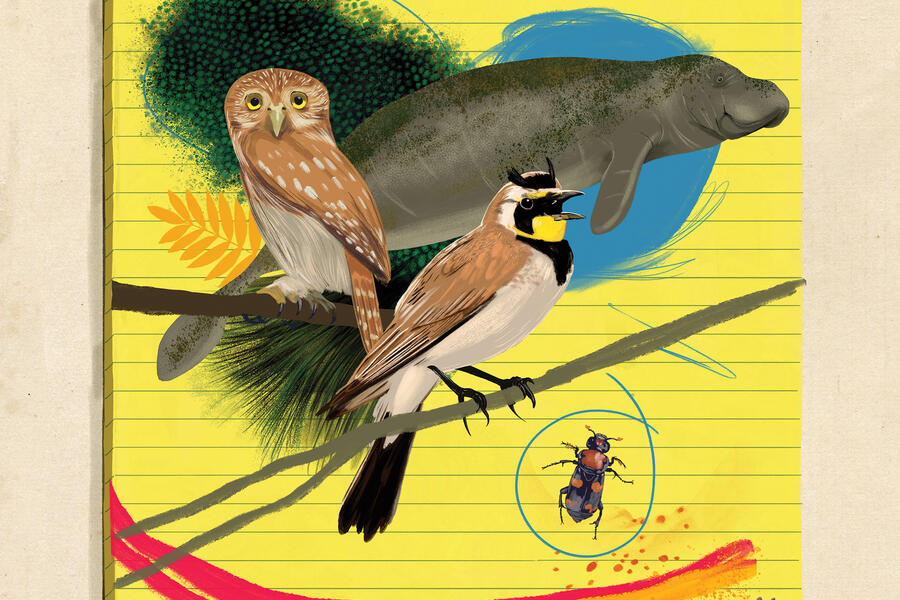

A listing of Glitzenstein's legal victories reads like an animal alphabet, with entries ranging from "charismatic megafauna" like bison, Canada lynx, eagles, whales, and grizzly bears to creatures as common as snails, bugs, and bats.

"One of the things that's happened in my work is I've come to appreciate the more obscure species that nobody else will necessarily love," says Glitzenstein, speaking from his home office in northwest Washington, D.C., where he keeps watch for cardinals, nuthatches, and the occasional migrant songbird, the family terrier-?chihuahua mix, Parker, under his feet. "I'm working on a case right now involving the American burying beetle, which happens to be a rather attractive beetle but not a creature most people are going to pay much attention to."

He's fought to protect the streaked horned larks of Oregon's Willamette Valley from agricultural practices that destroy their nests, the northern long-eared bat from mining threats in Minnesota, and the minuscule and feisty cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl from habitat loss in Texas and Arizona. "Part of what you do when you do this work is realize you can't just look at the wolves and the grizzly bears without understanding all the other creatures that are part and parcel of that ecosystem," he says.

In hundreds of influential federal cases, including several before the Supreme Court, Glitzenstein pioneered creative legal strategies that expanded the reach of the Endangered Species Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, and other legislation.

"One real evolution that we've seen in wildlife law is moving from just this project-by-?project set of challenges or controversies to thinking more holistically about how the way we do things systemically affects species and their habitat, and Eric's work is an example of that," says Daniel J. Rohlf, founder of the Earthrise Law Center at Lewis & Clark Law School.

Growing up in New York City, Glitzenstein from an early age found ways to bond with the natural world. "One of my earliest memories is going to the Bronx Zoo with my grandfather and watching him sneak in pieces of food to the wild dingo dogs, right in front of huge signs that said 'Please don't feed the animals,'" he says, laughing. "I'm going, 'I don't think that's such a great idea,' but he'd say, 'See, they like this,' and these wild dogs would come up to the cage and wag their tails. So from an early age I got the sense that we have to care about our fellow travelers on the planet."

One incident stands out. While on a canoe trip in Texas with his father and two brothers, they spotted a red-tailed hawk tangled in fishing wire high in a tree. "I got out of the canoe and shimmied up the tree, and suddenly I was face-to-face with this amazing animal," he says. Managing to capture the hawk and lower it into the canoe, they transported it to a wildlife rehabilitation center, where it survived to live out the rest of its life, having lost the use of its left wing.

His career path, in a sense, had begun to take shape.

Starting at Johns Hopkins as a science major, Glitzenstein soon switched to political science. He also joined the debate team, which he eventually captained and which proved to be the perfect incubator for his future courtroom skills. He enrolled at Georgetown Law with the intent to do public interest work, and while there Glitzenstein wrote for the Environmental Law Review and spent his first summer working for the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, now called Earthjustice. Upon graduation, he spent a year clerking for Judge Thomas Flannery of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, then joined Ralph Nader's Public Citizen Litigation Group, where he soon began broadening the organization's focus to include environment- and wildlife-oriented cases.

It was also at Public Citizen that Glitzenstein met fellow attorney Katherine Meyer, who became his wife as well as his legal partner. In 1993, the two founded their groundbreaking public interest law firm, Meyer & Glitzenstein.

"They accomplished something that is extremely hard to do, which is to create a premier public interest litigation law firm known for, among other things, its advocacy for animals and wildlife. And they were one of the first to do anything like this, while the field was still in its infancy," says Andrew Mergen, faculty director at Harvard Law School's Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic. Noting that few other law firms have been able to achieve anything close to Meyer & Glitzenstein's success, he adds, "It's a testament to how hard it is to do what they were doing that there aren't very many imitators."

Glitzenstein credits his and Meyer's roots at Public Citizen for honing the unusual and groundbreaking tactics that have resulted in so many landmark achievements.

In particular, the partners learned inventive ways to use administrative law, which governs the nuts and bolts of how federal agencies are required to operate. For example, he says, "we had learned how to pursue what are referred to as unreasonable delay cases, which basically just means, what do you do when an agency is dragging its feet and not doing what it's supposed to do to carry out its statutory mission?"

The newly minted firm employed just that tactic in one of its first big cases, challenging the Fish and Wildlife Service to address a mammoth backlog of species awaiting review for potential listing under the Endangered Species Act. Thanks to the resulting settlement, some 400 species were listed as endangered over the next four or five years, far faster than at any time since the act was passed. "Rather than deal with this on a single species level, we brought an entire case challenging their failure to have a process in place that expeditiously protected species, the way the law clearly contemplated they should be protected," Glitzenstein says.

In a similar approach, Glitzenstein has played a major role in protecting North Atlantic right whales, a critically endangered species on the verge of extinction, from being struck by boats. "Eric represented us in litigation essentially trying to hold the National Marine Fisheries Service responsible for implementing a regulation that it had identified for more than nine years as necessary to protect North Atlantic right whales," says Jane Davenport, a senior attorney at Defenders of Wildlife.

While this type of incremental rulemaking "isn't super sexy," Davenport says, it's often the best way to effect change by holding agencies accountable.

The firm took full advantage of a cluster of what are called open government laws, including the Freedom of Information Act, the Government in the Sunshine Act, and the Federal Advisory Committee Act. They offered transparency to the inner workings of agencies, making it much easier to challenge rules and reveal lack of enforcement. "If you don't know what the government's up to, or if you don't know what's going on out there, there's not much you could do about it from a legal standpoint," Glitzenstein says.

Such tactics have made Glitzenstein "a sophisticated advocate," says Mergen, who fought cases both with and against Glitzenstein during a long career in the Department of Justice's Environment and Natural Resources Division. "People in the Department of Justice did not like litigating against Eric. You underestimate him at your peril," Mergen adds.

His defeats still haunt him, however. "One loss that stays with me is an Endangered Species Act case that I argued in the U.S. Supreme Court and lost on a 5-4 vote," Glitzenstein says. The case, decided in 2007, sought to protect a number of species, including the Arizona population of the tiny but fierce cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl, which nests in saguaro cacti. Today its range has shrunk to the 45-mile-long Altar Valley just north of the Mexican border, and only a few hundred of the birds remain. "In this line of work disappointments are inevitable because so many cards are stacked against us—as well as against the wildlife we're trying to save," he says.

The declines can be painful to witness. One species he's fought to save, the Mount Graham red squirrel, is barely holding on, with fewer than 100 left. "Much of their habitat in Arizona was destroyed as a result of two congressional riders eliminating Endangered Species Act protections for the species," he says. "If they go extinct in the near future, it will be a result of very deliberate action by our government to allow that entirely preventable calamity to occur. And to me, that's incredibly tragic."

Even victories can take years and years of litigation, and often real results don't become apparent for far longer. Take the 10,000-acre Blackwater Canyon in West Virginia, a prime stretch of whitewater cradled in a deeply forested canyon that's been fought over by timber companies and environmentalists for 25 years. It was back in 2007 that Glitzenstein won protection for a relatively small section to protect the habitat of two listed species, the threatened flat-spired three-toothed snail and the endangered Indiana bat. It took almost two decades more, but in 2024 the rest of the canyon became part of the Monongahela National Forest.

That long view is a big part of what keeps him going, he says, along with the support of his wife and longtime law partner. "Being able to share victories and losses—as well as a healthy sense of outrage—with Kathy has been crucial for me." Now a grandfather, he's motivated by a commitment to the next generation as well. "At this point, I want to be able to tell my granddaughter that I've tried to do what I could to help animals so that she wouldn't just have to read about them in a book or see them in a zoo."

"Strategic" is a word that comes up over and over in descriptions of Glitzenstein's achievements, so it's no surprise that in his five years at the Center for Biological Diversity, he's focused on high-level strategy and coordination. Helming a staff of more than 50 lawyers spread across the country, Glitzenstein oversees teams litigating dozens of prominent cases, many of them with far-reaching implications.

"When you're talking about trying to make some of these much more systemic changes, like removing major dams, altering farming and pesticide practices, managing entire national forests in a different way to either protect species or to try to store carbon or minimize fire risk, that takes a lot of time and a lot of really good lawyers, people like Eric," says Daniel Rohlf, a wildlife law professor at the Lewis & Clark Law School.

A series of recent victories by the Center for Biological Diversity exemplifies the big-picture approach to environmental regulation that Glitzenstein has promoted from the earliest days of his career. In one settlement, reached in 2023 after more than 20 years of litigation, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency agreed to a slate of reforms designed to take threats to protected species into greater account when approving more than 300 pesticide active ingredients. Two other lawsuits filed in February 2022 and December 2024 challenge the Fish and Wildlife Service to stop the use of six widely used pesticides that the Center for Biological Diversity argues affect up to 97% of all endangered and threatened species. "There's been a huge problem with pesticides being registered and re-registered without looking at some of the serious impacts on endangered and threatened species, especially bees and other pollinators," Glitzenstein says.

While his new role undoubtedly removes him further from the courtroom, Glitzenstein remains deeply involved in many issues, among them the establishment of new permitting regulations that would allow renewable energy projects such as wind farms to bring themselves into compliance with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in exchange for adopting important protective measures. "Bird populations have plummeted by 3 billion birds over the last 40 years or so in North America, so it's a huge heartbreaking situation," he says. "And without those regulations, migratory birds will continue to be killed in extremely large numbers."

Creative tactics are going to be even more important in the coming years, with climate change now the primary driver of many threats to wildlife. "One of the big challenges going forward is that our statutes were drafted before climate change was on anybody's mind, so statutes like the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Air Act are poor tools to deal with climate issues," Mergen says.

Glitzenstein agrees: "Climate change certainly forms a critical context for all of this, so part of that analysis is, if you're not going to solve climate change overnight, what can you actually do to deal with some of these problems?" In the case of the manatee, for example, it will take addressing agricultural runoff and sewage discharge to prevent recurrence of the red tide responsible for the recent massive die-off.

Central to Glitzenstein's approach is understanding the pressures at work on the other side, often fueled by the industries, natural resources, and economic interests likely to be affected by species protection. "I've dealt with a lot of employees and biologists from federal and state agencies who are remarkably dedicated, and they're working under really, really difficult circumstances," he says. "They're trying to do one of the hardest things you could possibly do, which is to basically arrest and reverse a species' decline toward extinction when that has been happening over the course of decades. And when they try to do the things that would be necessary for that reversal, they're under this incredible pressure from economic and political interests."

Image credit: Getty Images

The current legal climate certainly calls for new approaches. "Much of my work today entails strategizing on how to expand protections for wildlife and the environment in an era when the Supreme Court is not sympathetic to a robust application of the federal wildlife laws," he says, noting that among other things the court has "decimated the EPA's authority under the Clean Water Act to protect wetlands—habitats that are of course vital for migratory birds and other wildlife."

Even so, he sees possibilities for compromise and collaboration. "Even in an anti-regulatory environment, there are actually very common-sense measures you can take that would be both good for the species and also good for the regulated industry or any actor who might be impacting a species. If people of good faith want to take a hard look at them, they can come up with those kinds of win-win solutions. So I think it's a mistake to think about this as a zero-sum game, that it's going to be all good or all bad."

Ultimately, it seems clear that saving the planet isn't going to come down to headline-grabbing victories but instead to the dogged, detail-oriented persistence of litigators like Glitzenstein, who see every creature as worthy of protection. "Climate change isn't just about the polar bear, swimming around with no ice floes. It imperils things big and small," says Mergen. "By bringing cases on behalf of overlooked creatures like the burying beetle that are very much suffering the consequences, I think Eric is really driving home how big an issue this is."

Or, as Glitzenstein himself puts it: "Manatees are these wonderful creatures that just sort of bop around and eat vegetation and have these wonderful families and aren't threatening to anybody. So if we can't protect a species like the manatee and help them survive, then is there no hope for anybody?"

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged animals