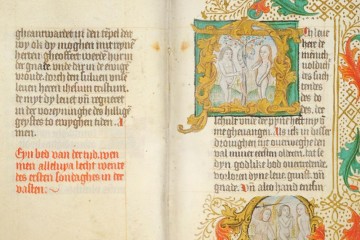

The medieval prayer book looks modern from the outside, with its sleek white leather cover added by a conservator for safekeeping. Open the pages, however, and peer into a bygone era. There, images of richly hued flora and fauna intertwine with saints, dragons, birds, and beasts. Gold-leafed borders and backgrounds glimmer, bringing to life biblical scenes rendered in bold burgundies, greens, blues, and yellows. "It's a tiny but incredibly beautiful 'book of hours,'" historian Earle Havens says about the pocket-sized devotional book commissioned in 1492 by Hans Luneborch, a wealthy merchant from the trading city of Lübeck in northern Germany.

Donated to Johns Hopkins University in 1909 by Baltimore railroad and banking magnate Michael Jenkins, the book up and disappeared from George Peabody Library around the mid-20th century, only to return roughly 50 years later in a box mailed without a return address. "What happened remains a mystery," says Havens, a curator of rare books and manuscripts at Johns Hopkins' Sheridan Libraries, and the inaugural director of its Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance. Today, the returned piece is a treasured opus—and one of more than 100 books and fragments in Sheridan Libraries' collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, which Havens and his team of curatorial fellows are cataloging and digitizing to make accessible to people everywhere.

"Our pre-1600 collection is full of unique, stunning pieces, and now, they'll be part of one of the largest digital libraries of medieval and Renaissance books in the world," Havens says about Digital Scriptorium, a free online database of pre-modern works owned by North American libraries and museums. Professors, scholars, and the wider public will be able to view, analyze, write about, and teach classes with "these time machines that transport us back and let us interrogate the past in new ways," he says.

Already, two of the Stern Center's world-renowned collections of early books have largely been digitized, thanks to support from the Arcadia Fund, a family-based philanthropy in the United Kingdom. One of these, Women of the Book, features 2,000-plus books and manuscripts about women dedicated to the life of the mind: nuns, female saints, healers, and miracle workers living between 1450 and 1800. Another, the Bibliotheca Fictiva Collection of Literary and Historical Forgery, consists of more than 3,000 faked and forged manuscripts and books by and about forgeries from the ancient world to the 21st century. Among them are a made-up "eyewitness" account of the fall of Troy; a forged book from Shakespeare's library, with annotations suggesting the bard's interest in a plot to kill the king of England; and a first edition of the infamous "miscegenation pamphlet," devised by political enemies to tarnish Abraham Lincoln's second presidential campaign.

Now, Havens and his colleagues are starting to comprehensively describe and digitize Johns Hopkins' collection of early manuscripts, each crafted by hand in a monastic or secular scriptorium across Western Europe, before the printing press (invented by Gutenberg around 1450) became a mainstay of bookmaking. The collection offers a window into the rise and dominance of Catholicism across Europe during the Middle Ages, followed by the Renaissance, the Protestant and Catholic reformations, and the growth of learned societies and universities.

Image caption: With Earle Havens, curator of rare books and manuscripts, and J.J. Haddad, a doctoral candidate in the history department

Video credit: Presented by Hopkins at Home, Sheridan Libraries and Friends of the Johns Hopkins University Libraries

"A single book could take as much as a year to copy and involved a complex division of labor," Havens says about the toilsome tasks undertaken by scribes and other bookmakers, who fashioned pages from vellum (or calfskin) and parchment (sheep, goat, or calfskin). The process entailed soaking and softening the hide, scraping off the animal's hair, and stretching and cutting the skin into an appropriate page size. Rows of straight lines were drawn or etched onto each leaf, upon which scribes wielded quills and ink to copy by hand word after word from an existing text. On the finest books, illuminators rendered intricate scenes in vibrant pigments and thin sheets of gold and silver, creating an art form that many consider exquisite to this day.

Collection highlights include the massive Sententiae by theologian Peter Lombard, a 12th-century book that shaped church doctrine and served for centuries as the standard textbook for Christian theology. "Lombard took bits and pieces from biblical scripture, ancient philosophers, and other theologians and compiled them for the first time into a single book that attempted to identify and rationalize a uniform orthodoxy within the Roman Catholic Church," Havens says.

Made of thick vellum, the book's pages show imperfections in the animal's skin—a cut or scar, for instance—which scribes tended to write around or stitch with thread. They abbreviated as many words as possible to save space and make the production more efficient and less costly. Even still, "a book of this length was expensive and likely took an entire herd of animals to make," Havens says.

The oldest medieval manuscript harkens back to 10th-century Germany. A fragment from a liturgical book, it features 14 lines from the New Testament gospels of Luke and John about John the Baptist. "Worth noting are the markings in the margins and above some of the words—they're the earliest form of Western musical notation, a primitive, largely gestural style we now call adiastematic neumes," Havens says. "Priests and monks likely knew the melody by heart but used these freehand notations as an aid to memory when practicing the liturgy."

Marginalia, the notes and marks scribbled along the edges and between lines of text, are another core research focus for Havens, who is trained in paleography (the study of early handwriting) and can delineate, say, the more rounded, legible letters of Carolingian script from the narrow, spiky letters of German Gothic script. "What's written or doodled in the margins enables us to peer over the shoulders of readers from hundreds of years ago to see how they engaged with texts at specific moments in history," he says. "The passages they underlined or marked, the thoughts and [critiques] they jotted down—all of this is fascinating to study," capturing fleeting notions and ideas from those who lived long ago.

Posted in Arts+Culture