War and revolution often spur in artists visions of radical change.

That's what happened in early 20th-century Europe when the Great War and Russian Revolution uprooted life for millions. From the flesh-rotting diseases of trench warfare to the toppling of the Russian, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and German empires, world events propelled artists to conceive of something better and new—something more just and egalitarian, where peasants didn't face famines and workers didn't sleep crammed together on factory floors.

Offering a glimpse at the social change envisioned by artists of that era is Art and Graphic Design of the European Avant-Gardes, the inaugural exhibition of the Irene and Richard Frary Gallery at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center in Washington, D.C. The recently opened show runs through Feb. 21, offering a look at rare art, photography, books, periodicals, and ephemera by artists and intellectuals, largely from Central and Eastern Europe, working between 1910 and 1941 to come to terms with their upturned worlds and build anew.

Named after Richard Frary, A&S '69, and his wife Irene, the 1,000-square-foot gallery features 75 works from the extensive collection of avant-garde art donated to Johns Hopkins by the Frarys. The exhibit "puts the spotlight on the diversity, depth, and international interconnectedness of avant-garde publishing from Central and Eastern Europe in ways that are only starting to be studied and recognized," says Philipp Penka, the show's curator and a rare books dealer in Berlin.

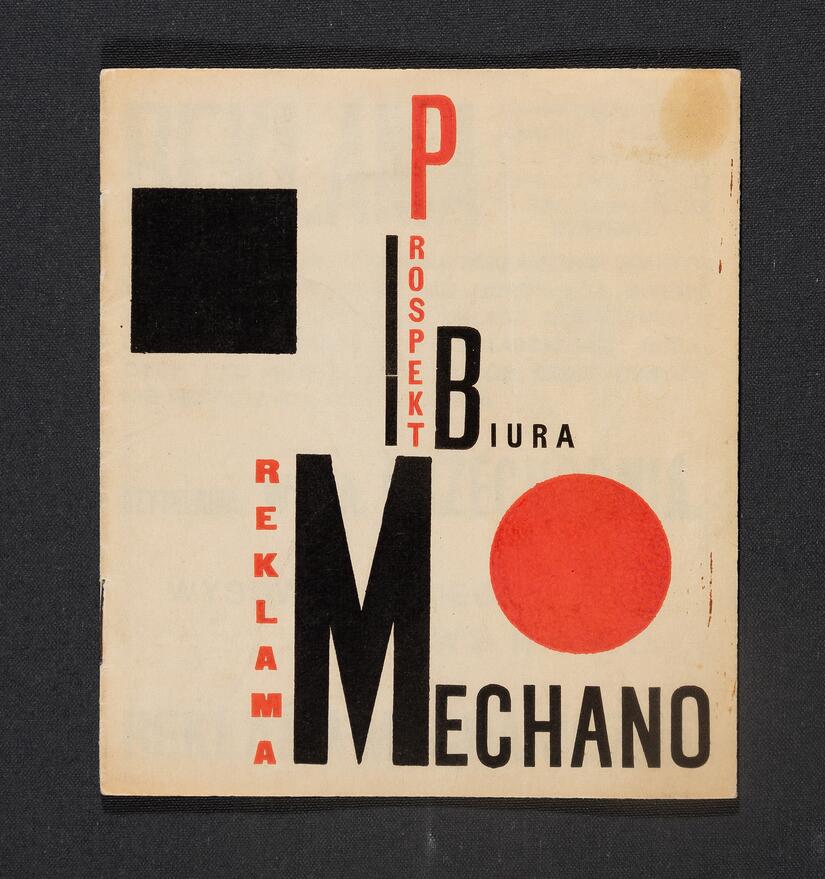

Image caption:Promotional leaflet for the Mechano advertising agency, Henryk Berlewi, Warsaw, 1924

Image credit: Photographed by Bruce Schwarz

The exhibit, then, offers insight into the nuanced social and historical milieu surrounding art from this period—and into the turmoil still stewing in Central and Eastern Europe.

It features work by influential artists like Kazimir Malevich, who painted the iconic Black Square in 1915, attempting to erase notions of art aligned with the bourgeois tradition—namely, that art should represent reality and be aesthetically pleasing—and start over with a single geometric shape. To the Ukrainian-born artist, his square represented the dawning of a new age, "the face of the new art … [and] first step of pure creation in art," he wrote in 1919.

Although Malevich's original painting resides in Moscow, the show includes dozens of references to his square and other abstract work by him. The square plays a star role, for instance, in the Yiddish children's book About Two Squares (1922) by Russian artist Lazar Markovich Lissitzky, known as El Lissitzky. Using the abstract language of black and red squares, the book relays the rise of a new Soviet order in Russia, while instructing young readers to cut out shapes and construct new possibilities, metaphorically, for Russia's future.

This idea of construction shows up time and again in Eastern and Central European art from this era—hence the art movement being dubbed Russian constructivism, one of several -isms represented in the show, which traces the evolution from futurism and Dada to suprematism, constructivism, and surrealism.

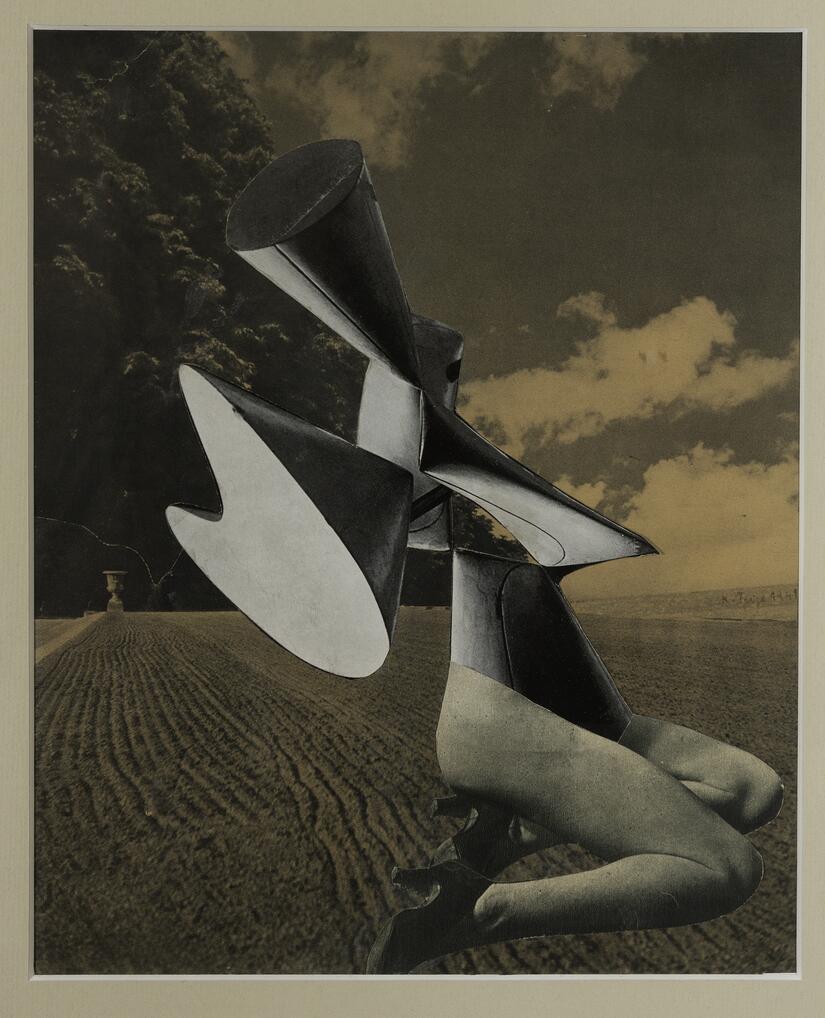

Image caption:Untitled photo collage, Karel Teige, Prague, 1941

Image credit: Photographed by Bruce Schwarz

Art historians like to categorize objects by movements, but visitors can see in the exhibit how much these groupings overlap, says Penka, who holds a PhD in Slavic languages and literatures from Harvard. "A Dada artwork may be just as futuristic as a futurist or constructivist work, and vice versa," he explains. "There is a playfulness and similarity of color, typography, and other elements shared throughout these avant-garde art movements, despite differences in geography and politics."

While the exhibit features work by other known artists—among them, the Russian constructivist Aleksandr Rodchenko and Italian futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti—it focuses on those less known, such as Lajos Kassák, a working-class artist and writer from Hungary. Kassák experienced firsthand the grueling nature of factory work during this period—and took up publishing to promote change.

Designs on display from a progressive journal he founded, MA, depict the geometric shapes and experimental typography that came to symbolize left-leaning ideologies and avant-garde movements during and after World War I. For Kassák, the minimalist imagery represented a departure from bourgeois decadence, a stripping away of ornamentation to get to the core purpose of art to transform society, "not to die on the wall," he wrote in a 1922 issue of MA.

Like much of the avant-garde, Kassák embraced socialist ideologies and better conditions for the working class. But as Penka warns, "we can't ascribe leftist leanings to every avant-garde artist in the show—their belief systems varied, changed over time, and were more nuanced." For one, the founder of the futurist movement, Marinetti, was a fascist who supported the brutal Italian dictator Benito Mussolini despite creating work that influenced leftist artists for decades to come. Marinetti's Zang Tumb Tumb, an extended poem from 1913, stands out with its atypical font, onomatopoeia, and nonsensical words capturing the horrors of modern warfare.

Video credit: Marinetti reading Zang Tumb Tumb, 1914, Museo Civico Modeno

"Zang-tumb-tumb-zang-zang-tuuumb tatatatatatatata," the poem reads, echoing the machine guns he encountered as a war reporter.

Marinetti's influence, like Malevich's, was wide-ranging. It shows up across the entire exhibition, appearing, for example, in the work of Georgian artist Il'ia Zdanevich (also known as Iliazd), Polish designer Henryk Berlewi, and Ukrainian artist and poet Mykhailo Semenko. A futurist who took up the plight of the proletariat, Semenko supported Ukrainian independence and published in his native Ukrainian language—acts that led to his arrest and execution as part of the Great Purge of 1937, when Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin orchestrated efforts to punish and kill an estimated 1 million people suspected of harboring anti-Soviet sentiments.

Image caption: Art on view in the Frary Gallery, including (in orange) Marinetti's Zang Tumb Tumb

Image credit: Will Kirk for Johns Hopkins University

Stalin had banned abstract art years earlier, in 1932, making it hard for avant-garde artists to continue unless they transitioned to the only permitted art form: propaganda paintings in the style of social realism. Many like Semenko went into hiding or changed their ways—but were still hunted down and killed for their contrarian viewpoints.

The show's inclusion of artists like Semenko helps round out the story of Europe's shifting boundaries and power struggles between the two world wars, while shedding light on lingering controversies like the recent ban on speaking Russian in Ukraine—an effort of the Ukrainian government to preserve their native language and stop what it refers to as "centuries of linguicide."

"The pieces on view contextualize the stories and history we've heard for years or maybe learned as kids in school," says Caitlin Berry, the Frary Gallery's new director, who comes to Johns Hopkins from the Rubell Museum DC (a mecca for contemporary art fans). "They add complexity and humanity to events that happened 100 years ago but still affect our world and the lives of millions."

Penka agrees—and adds that the idea of a single Russian avant-garde movement, as sometimes described in art history, is not quite accurate. "Many different voices and nationalities make up what has historically been categorized as Russian or Soviet," he says. "The reality is more complicated."

The exhibit is free and open to the public. Visit washingtondc.jhu.edu to plan a visit or view part of the show virtually.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged visual art