There are 200-ish citizens of Curdle Creek, a remote village in 1960s America. But what it takes from its residents—and what they must give to stay there—explains why those population numbers fluctuate.

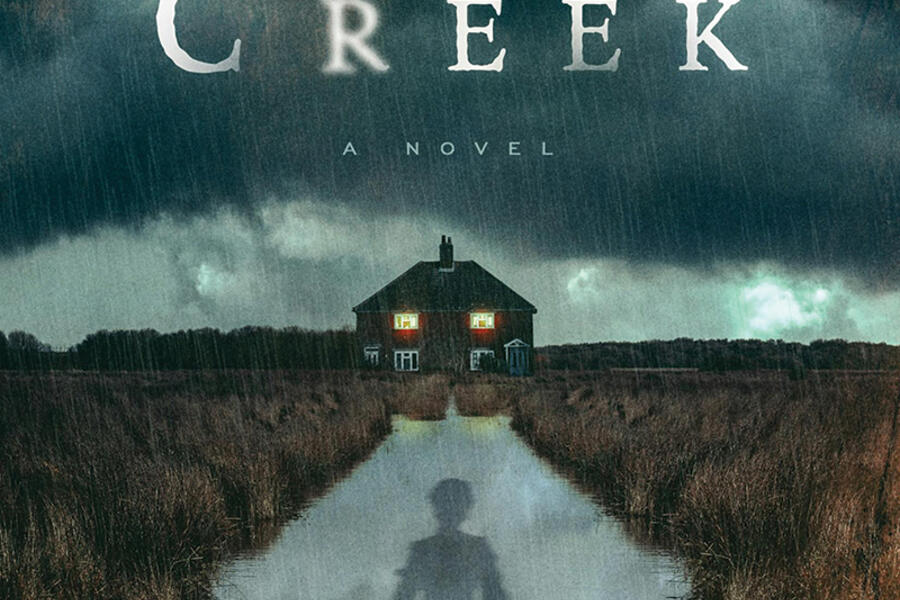

The secrets of the village create the cozy, creepy world of Yvonne Battle-Felton's Curdle Creek (Henry Holt). The novel, the author's second, is a richly detailed and eerie tale of what happens when protection against a cruel world begets its own evil. In sinister shades of Shirley Jackson, the author creates both a singular society and a sometimes wryly humorous heroine whose dissatisfaction becomes her own strength.

Osira Turner is a 45-year-old widow beset by a complicated mixture of grief and a growing sense of dread about the town she's lived in her whole life. Curdle Creek, created as a sanctuary for free Black people against racial violence in the 1800s, has a particular set of rituals to maintain its numbers and its way of life.

And what fun and clever names these rituals have. There's the Running of the Widows, which sounds like a merry relay race, except it's actually how the town assigns new spouses to those whose previous mates have been the subject of another ritual, the Moving On. (Hint: It involves sticks and rocks, not trucks. And it's involuntary.)

Already the subject of scorn because her children left town to escape this ominous reality, Osira badly loses the Running of the Widows. Then her father, who's been chosen to be, well, moved on, flees. Meanwhile, her controlling mother inherits new status as Town Mother because of the sudden and mysterious vacancy left by the death of the previous title holder. Battle-Felton, A&S '09 (MA), does a masterful job weaving the banality of these evils, described so matter-of-factly. It's all for the good of the town, you see.

Curdle Creek is reminiscent of M. Night Shyamalan's The Village, about another insular community created allegedly as a shield against the outside world but becoming a weapon of fear and control. Battle-Felton skillfully weaves an allegory about the intersection of racism, paranoia, and cultlike authority masquerading as tradition and safety. It's stunningly disturbing, but a journey worth taking.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged book review