Footprints of a live rooster strewn across sand. Fried chicken wrapped in gold chains. A bloody Band-Aid in a jar.

This odd mix of accoutrements was part of Art as a Verb: The Evolving Continuum, a groundbreaking 1988 exhibition co-curated by the art historian, curator, and artist Leslie King Hammond, A&S '73 (MA), '75 (PhD).

"The show set out to deliberately rattle the art world," she says. "It was a huge risk."

At the time, King Hammond was dean of the graduate school at the Maryland Institute College of Art, a position she started in 1976, "when MICA's president announced my appointment at a faculty meeting, and my colleagues let out an all-too-audible gasp and one loud expletive," King Hammond says. But more than a decade had passed since her unsettling start as one of the few Black women in the United States to hold a leadership position at a college or university—and the only one to run a graduate art program. King Hammond, though initially jarred, had moved on.

She was on a mission to make things right for Black and women artists, who had been overlooked and excluded by the art world for centuries. "At that time and still today in some cases, Black artists especially weren't part of college art history courses and the intellectual landscape of our society," King Hammond says. The world was missing out on seeing "the creations of all humans as worthy of investigation, examination, recognition, enjoyment, and representation."

King Hammond approached art and artists in a way that differed from her more formal graduate training. "I learned to listen," she says. "I learned not to force or impose the art history canon but to inspire artists to connect with the canon in authentic ways and ultimately create from within."

Her methods worked. Art as a Verb was a huge success, opening at MICA and moving on to show in New York City. New York Times art critic Michael Brenson described it in 1989 as a show so poignant "that it [was] at times overwhelming." And King Hammond would go on to build a long list of accomplishments, including an array of grants, fellowships, and awards such as a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Video credit: Craft in America, PBS

Although King Hammond retired in 2008 and is now dean emeritus of MICA's graduate school, she continues to make things happen for artists—and to play an active role as an artist herself in Baltimore's maker spaces and art communities. In 2009, she founded MICA's Center for Race and Culture to investigate the interplay of art, race, culture, and identity. Then, in 2010, she co-curated a major exhibition, The Global Africa Project, at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, followed by a traveling show in 2013, Ashe to Amen: African Americans and Biblical Imagery.

Now, on the brink of her 80th birthday, King Hammond exudes a glow and energy suggestive of a life lived fully and exuberantly, not without obstacles but with a mindset that has propelled her to overcome hardships and find a way forward. She looks back on her roughly 50-year career and considers Art as a Verb—revived on the second floor of the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of a recent exhibition—emblematic of her life's work to elevate Black artists, largely through her use of unconventional tactics that skirted common pathways in the art world.

"I had no choice," King Hammond says. "I didn't have a guidebook, and I've never been a follower."

King Hammond recalls when MICA's president, Fred Lazarus, approached her in the late '80s with a question: "Why are you always curating shows in other cities, in other galleries and spaces, but not here at MICA?" She told him simply, "I've never been invited."

With Lazarus' invitation extended, King Hammond reached out to her longtime friend and colleague Lowery Stokes Sims, A&S '72 (MA), then a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

King Hammond and Stokes Sims made a formidable pair, having met as preteens in Girl Scouts in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens, New York. Growing up against the backdrop of the civil rights and feminist movements of the 1960s, King Hammond remembers being unable to find many books on women artists at her local library—and practically none on Black artists. "As I looked for my sense of place, history, identity, and agency, I couldn't find anything that specifically dealt with me," she says.

Undeterred, King Hammond and Stokes Sims would go on to study art together as undergraduates in the 1960s at Queens College, City University of New York. From there, they entered graduate school in art history at Johns Hopkins University, learning the formalities of a discipline that required reading and writing in French or German and focused largely on the Western canon.

Video credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art history at that time was "a very staid discipline dependent upon [using] the voices of [scholars] to validate what you would eventually convey to your students, whether as a curator or a professor," she says. This wasn't the approach she wanted, though she knew the program could help in the long run.

After earning her master's degree in 1972, Stokes Sims returned to her hometown, New York, to start what became a 27-year career at the Met. But King Hammond stayed on at Johns Hopkins, writing a dissertation on the American artist William Henry Johnson and graduating in 1975 with a PhD in art history.

Years later, as the two talked through possibilities for the MICA exhibition, they found themselves returning to a question debated rigorously in the art world at the time: What does "Black art" even mean?

For much of the country, Black art meant portraits and images of Black people suffering the atrocities of slavery, picketing in protest lines, or rising above these challenges—"what I call corrective portraiture," King Hammond explains. "We didn't want our show to do that."

Instead, the duo tapped into an idea fermenting at the time—essentially, that art could be more than a static object. Art could fuel or represent action. It could change preconceived notions and lead to new understandings. Art, by its very nature, could be not just a noun but also a verb.

The idea appealed to King Hammond, who had transitioned her own art practice from large color field paintings to mixed-media creations inspired by her family's roots in Barbados and changes happening in society. Now, as dean of MICA's graduate school, she could create a show with contemporary artists who were also working to activate change. And her students would be right there in the thick of it, on MICA's campus, to learn firsthand from the experience.

King Hammond and Stokes Sims wanted artists who made art not to sit in galleries and look pretty but to stir new thoughts and possibilities in audiences. Moreover, they wanted artists to kick-start the process of reversing negative perceptions of a whole swath of humanity left out of world culture and history.

"Some artists around that time were intentionally turning the conventions of the art world on their head, because the art world as it existed hadn't worked for them," King Hammond says. And the elitism of high society art circles was unappealing. Artist David Hammons, for example, stated in a 1986 interview: "The art audience is the worst audience in the world. It's overly educated. It's conservative. It's out to criticize, not to understand. And it never has any fun. Why should I spend my time playing to that audience?"

Instead of working within the confines of a single medium, Hammons created site-specific art made using found objects from Black urban life—hair from a barber shop, bottle caps, baby oil, basketball hoops, hair gel, liquor bottles. He confronted racism head-on and saw himself as a cultural outsider, with King Hammond perceiving him as a "paramount provocateur … one you could count on to cause trouble," she says, laughing.

Hammons made the cut, becoming one of 13 artists selected for the opening exhibition at MICA. Eleven of the 13 artists were female, largely because "the feminist movement that started in the 1960s and had run through the '70s ignored Black female artists," King Hammond says. These artists needed opportunities. "Many were trying to break down, shake up, and throw back possibilities about what art could be or not be, as though … tossing a can of dice on the ground and waiting to see what kinds of options [exist] for consideration," she says.

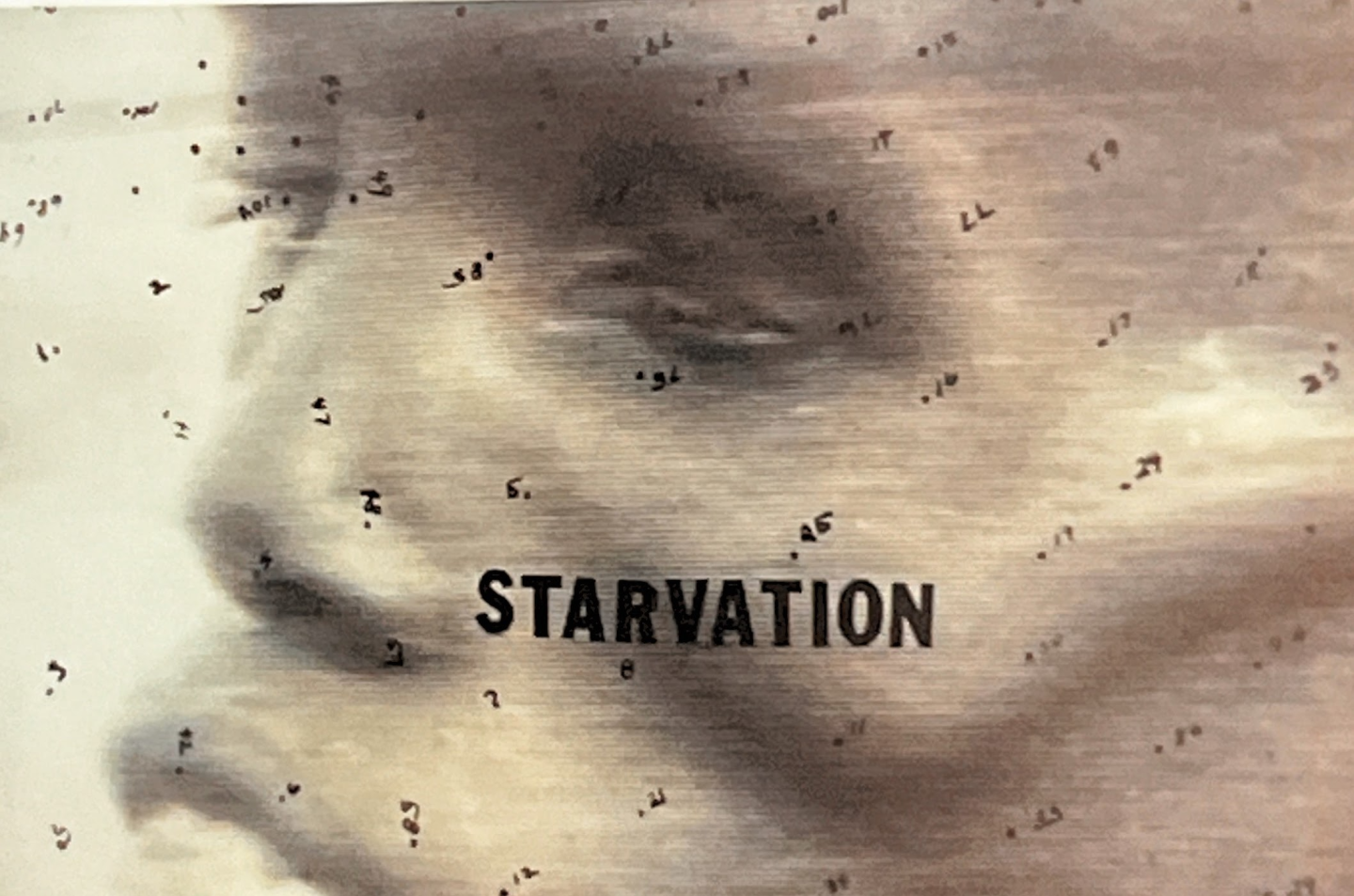

Image caption: Howardena Pindell. War_Starvation (Sudan #1), Video Drawing series, 1988. Art as a Verb: The Evolving Continuum. Courtesy of Leslie King Hammond.

As co-curators, King Hammond and Stokes Sims spent countless hours running possibilities by each other. "We were both in a very difficult terrain for African American women, and we held on to each other as cohorts and sounding boards," King Hammond says.

Stokes Sims agrees. "If you think of that line from A Tale of Two Cities, we came up in the worst of times and the best of times," she says. "It was a time of turbulence and upheaval, but we saw possibilities and were ready and willing to use our imagination, grit, and smarts to go for it."

Together, they selected artists of burgeoning international acclaim. Some, such as Hammons, Howardena Pindell, and Adrian Piper, confronted social issues head-on, while others like Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, Senga Nengudi, and Maren Hassinger worked more metaphorically in the realm of the abstract.

Piper, for instance, who earned a doctoral degree in philosophy from Harvard University in 1981, used art to rouse audiences into seeing their own racist ideologies and belief systems. As a Black woman, Piper had experienced plenty of racism herself, whether in academia or as an artist attempting to make it in a closed-off art market.

For Art as a Verb, Piper's Vanilla Nightmares series mined the implications of her experiences. The series' pieces juxtapose stereotypical etchings of Black people with clippings from race-related stories published in The New York Times. One piece in the series, Vanilla Nightmares #2, features a reclining, nude Black woman sprawled across stories from the June 20, 1986, issue of the Times. The figure's body suggests heightened sexuality, but her facial expression—especially her eyes—conveys distraction and disinterest. Beneath and alongside her, articles loom about Black unrest in U.S. communities and South Africa's apartheid.

The Birthing Chair, an intricate piece of mixed-media beadwork by Baltimore artist Joyce Scott, delved into issues about women's bodies. Here, Scott tapped into the often forgotten form of childbearing equipment that helped women deliver babies for centuries—but fell out of practice in industrialized nations for much of the 20th century, when male physicians advocated for women to give birth lying supine on a bed with their legs in stirrups, often with the aid of forceps.

Made of tiny, crystalized beads, Scott's birthing chair looks innocent from afar, as though it would fit in among the porcelains of a Victorian display cabinet. But upon closer look, it startles and stirs, with its fair-skinned figurine turned upside down on the chair, giving birth to a dark-skinned child. "When the show moved to the Metropolitan Gallery in New York in 1989, the trustees excluded it from the exhibit," King Hammond says. "They didn't want to see and really couldn't fathom a white woman giving birth to a Black child."

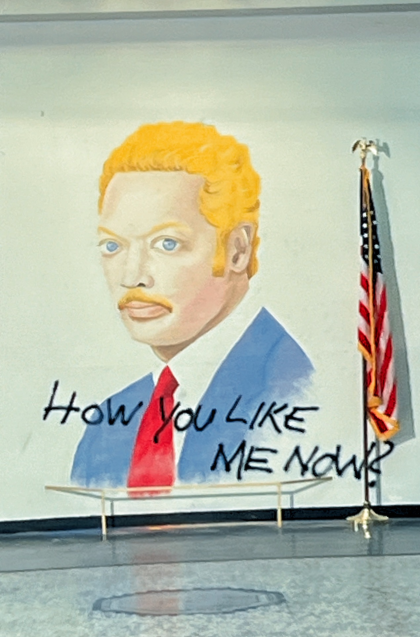

As expected, Hammons jolted audiences with a larger-than-life chalk drawing, How You Like Me Now? of civil rights activist and politician Jesse Jackson, displayed beside an American flag. Only instead of depicting the activist as he was in reality—a Black man—Hammons portrayed him as a white man with blonde hair and blue eyes. When King Hammond first saw the piece, "it was a total shocker but exactly what was needed to get people out of their mental rut of stereotypical assumptions."

Image caption: David Hammons. How You Like Me Know? 1988. Art as a Verb: The Evolving Continuum. Courtesy of Leslie King Hammond.

Both the Metropolitan Gallery and the Studio Museum in Harlem rejected Hammons' piece, fearing it would shock and disturb the public.

"But that's all right—he got them back," King Hammond says, chuckling as she continues the story.

"He went to the Pathmark supermarket, got a package of drumsticks, fried them up, tied them with gold chains, and then came down to the museum to present [his creation] as his new sculpture, while the chicken was still warm. When the museum called asking me what to do, tears rolled down my face I laughed so hard. But I pulled myself together and said, 'Give him a nail and a hammer, show him what spot, and let him hang it on the wall.'"

Early in the exhibition planning, King Hammond and Stokes Sims made a bold decision. They gave artists carte blanche to create what they wanted, going against the grain of curators to orchestrate exhibitions from the top down. This bottom-up approach stemmed from King Hammond's experience in the classroom, where she "discovered that interesting art arises when students, no matter their race, pull from deep inside their own experiences and belief systems about the world and their surroundings," she says.

Yet in the late 1980s, as Art as a Verb came to fruition, King Hammond and Stokes Sims worried their approach might upset the art world too much—especially donors and funders. "When we applied for funding, we weren't sure how [potential sponsors] would react to our complete lack of specifics about what each artist would create," King Hammond says. "But as it turned out, we received funding from every single agency we reached out to."

With funding intact, King Hammond could rest more at ease with the show's deliberate shake-up of prevailing attitudes and conventions. She could do things her way, which meant playing a new sort of curatorial role, more as facilitator than visionary or boss. But this approach came with a downside: She was becoming the errand girl. "As opening day [neared], I was saddled with all of these artists asking me to run out for things like cornmeal, newspapers, you name it," King Hammond says. "I had just arranged for four truckloads of branches. What would be next?"

Also see

Then it hit her: the rooster.

One of the artists, Charles Abramson, had suddenly died, and another artist had come in— Abramson's colleague Jorge Luis Rodríguez—to complete the installation, King Hammond says. Days earlier, Rodríguez had told her: To do this right, I need a live white rooster. The request had slipped her mind in the frantic lead-up to the show.

Realizing her mistake, King Hammond felt a wave of panic, she says, knowing she had forgotten something important. Both Rodríguez and Abramson had been practitioners of Santería, an Afro-Caribbean religion that developed during Cuba's slave trade in the late 19th century. In keeping with the religion's rituals and practices, Rodríguez wanted the rooster to represent Abramson's spirit, while serving as a protective force and warding off ill will. King Hammond needed to find one—fast.

She asked friends and co-workers. She called local veterinarians. No one had a rooster. Then she remembered: MICA's media relations director had scheduled her to do an interview about the exhibit that afternoon with a local TV station. "Why couldn't I use it as a chance to find the live chicken needed for the exhibition?" she reasoned.

After King Hammond gave her spiel about the exhibit, the anchor turned to her and asked, "Dr. Hammond, do you have anything else you want to say?" The curator then made her plea: "I need to get a live white rooster to honor one of the artists who passed away. I'm not going to kill the rooster. I'm not going to hurt it. I'm not going to cook the rooster. I will rent the rooster and give it back. Please call me if you have one to loan."

Almost immediately, a MICA staff member who lived on a farm and had watched the news segment reached out to King Hammond, and that's how Rudy the white rooster became part of the show. "He [arrived] in a cage, and he danced around and made a fabulous sand pattern on the floor," she says.

With Art as a Verb nearly 40 years in her rearview, King Hammond considers it a standout moment in her career—one that lives on through various iterations of exhibitions hosted at other places, from Spelman College in Atlanta, and Reed College in Portland, Oregon, to the second floor of MoMA.

Looking back, she says she can see more clearly the many connections among her work as an administrator, professor, artist, and curator, with each area feeding into and inspiring the others. "I sometimes called myself a 'way maker,'" she says of her unique ability to help artists of all levels find a way forward, whether college students in classrooms or those exhibiting nationally and globally. "I gave artists a license to create."

Image caption: Lowery Stokes Sims (left), just after receiving an honorary doctorate from MICA in 1990 following Art as a Verb. Here, Stokes Sims is pictured with her mother, Bernice Sims (middle), and King Hammond (right). Note that Stokes Sims also earned a PhD in art history from the Graduate School of the City University of New York in 1995.

King Hammond illuminated the path for hundreds of artists during her time at MICA. Among them are painter Amy Sherald, sculptor and performance artist Nick Cave, photographer Dawoud Bey, mixed-media fiber artist Sonya Clark, and "Afro-Deco" furniture artist and muralist Tom Miller.

"Folks [like King Hammond] were clearing the way," says award-winning artist and MICA faculty member Ernest Shaw Jr., who credits King Hammond's mentorship with his focus on teaching. "[She was] clearing the brush for those to come after and do their work without having to do the heavy lifting, because some of the heavy lifting was already done."

With her devotion to nurturing artists, King Hammond never lost sight of the challenges of making a living in a creative field. More than 200 student artists enrolled in art programs at MICA and other colleges and universities through the Ford Foundation's Philip Morris Fellowships for Artists of Color, a program King Hammond directed for 13 years. "I always knew the biggest obstacle was money," she says.

Recently, the art historian convinced Stokes Sims to move to Baltimore so the two could spend more time, say, enjoying King Hammond's legendary potato salad—and continuing what has been a lifelong conversation about art. "I would not be here with any modicum of sanity or perspective were it not for Leslie as the chief member of my art historical posse," Stokes Sims says. "We've spent our lives working together on what I call 'crimes of opportunities' that we seized upon and navigated, sometimes in a split second—and always with a hypersensitivity to the ever-shifting political winds as we rolled from one project to another."

Both agree that plenty of work remains to make up for the long stretch of time Black artists were left out or never permitted to succeed. "The job is far from finished," King Hammond says.

In today's world, still ripe with inequities, she continues to juggle one project after another, having wrapped up her role as a historical consultant for a TV series, Kindred, based on Octavia Butler's 1979 novel about a time traveler to the antebellum South. Currently, she's working on a writing project about the Black figurative painter and printmaker John Wilson.

King Hammond also devotes time to her own art-making practice, largely made up of quilting and mixed-media art installations. "The process of making isn't about feeling helpless or hopeless—it's an outlet for [working through] stress, tension, and fear," she says. Whether it disrupts a whole country's consciousness or gets tucked away on a family member's shelf, "art is a product of positivity."

Emily Gaines Buchler is a senior writer at Johns Hopkins University.

Alanah Nichole Davis contributed to the reporting of this story.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged art history