In a sense, our story begins more than 500 million years ago in the late Proterozoic Era. That's when rifting continental plates spawned cataclysmic, lava-spewing volcanic eruptions as the ancient Iapetus Ocean was formed. Some 100 million years later, the tectonic plates collided in massive terrestrial upheavals that birthed the Blue Ridge Mountains, including a section called South Mountain straddling Maryland and Pennsylvania.

But let's start slightly less far back in time: 1891. That's when, within the hodgepodge of midtown Victorian buildings constituting Johns Hopkins University's initial home, the bewhiskered academes gathered—perhaps in a smoke-filled room—to review the latest applications for graduate study and advanced degrees. One candidate was particularly promising, possessing no fewer than three bachelor's degrees and a master's degree in geology from the University of Wisconsin. While pursuing a master's, the applicant had been introduced to microscopic petrography, then an emerging field of geological study, where thin slivers of rock are examined under a microscope. Accessing Hopkins' advanced facilities for such research is what drove this person to apply. And, if academic bona fides weren't enough, there were letters of support from multiple professors at Wisconsin as well as from Edward Griffin, a Hopkins dean and professor.

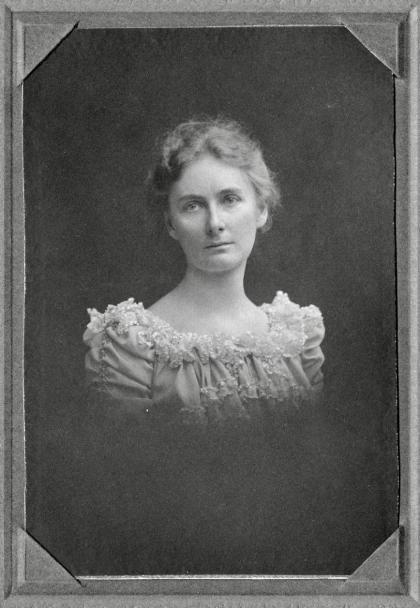

It should have been more than enough to slide this candidate's paperwork into the Accepted for Admission pile, save for one thing. Her name was Florence Bascom, and she was a woman. Johns Hopkins was in many ways the apotheosis of academic thought for the age, the best of German and British academic traditions fused together to create the nation's first research university—all largely the work of visionary founding President Daniel Coit Gilman. It was bold, modern, and focused on productive research. But it wasn't coeducational. The doors were shut to half the population.

Spoiler alert to events that transpired more than a century ago, Bascom successfully crashed the boy's club. In 1893, she became the first woman to receive a PhD (or any degree, for that matter) from Johns Hopkins University. It propelled her on to a brilliant geological career marked with other firsts: first woman to work for the U.S. Geological Survey, first woman officer with the Geological Society of America, first woman editor of The American Geologist. Bascom founded Bryn Mawr College's Geology Department in 1895 and taught there for more than 30 years, mentoring a generation of women geologists while engaging in annual Geological Survey fieldwork and publishing some 40-odd papers.

Along the way, Bascom picked up a nickname: the Stone Lady. This moniker was perhaps bestowed on her by the bewildered country folk she encountered while doing fieldwork in rural Pennsylvania and Maryland. (A woman tromping through the backcountry wielding geological hammers and other tools might have been a strange sight.) It's tempting, not to mention apt, to say the Stone Lady shattered the glass ceiling for her sex at Hopkins, but the full story is more curious, complicated, and frustrating than that. After all, women undergraduates weren't admitted to Hopkins until 1970—more than three-quarters of a century after Bascom collected her sheepskin.

Why all the fuss over women studying alongside men? In Gilman's inaugural address at the university's founding, he explained that his opposition to coeducation was to shield women from "the rougher influences, which I am sorry to confess are still to be found in colleges and universities where young men resort." In other words: Boys will be boys, and the "delicate sex" should stay clear.

"Hopkins was a leader in the way they approached graduate education, with fellowships and an emphasis on primary research," says Michael Benson, author of Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University. "And they could have been a leader as it relates to the admission of women students, but they missed the mark. When you go back and read a lot of the minutes from the trustee meetings, it's clear that there was an ardent strain among the board in opposition to the admission of female students."

Bascom's receiving her PhD represents Hopkins at its best. The superlative education she received here empowered her to be a pioneer. How the Hopkins administration treated her and the handful of her brave 19th-century peers who dared to invade the sacred scholastic domain in dresses and high-button shoes was, on the other hand, not the university's finest hour.

Bascom grew up in a family that emphasized education and placed no limits on female aspiration. She was born in 1862 in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where her father, John Bascom, was a professor of rhetoric and English literature at Williams College. Her mother, Emma Bascom (née Curtis), had attended multiple schools including the Patapsco Female Institute in Ellicott City, Maryland. Both parents were progressive thinkers and suffragists. In 1874, when she was 12, her father accepted the position of president of the University of Wisconsin. The 25-year-old land grant school had a growing campus in Madison, and the family moved west. One of the first things President Bascom did was to eliminate the separate female college operating within the university, allowing women to join the larger academic community. Coeducation was increasingly becoming the norm as the 19th century wore on, especially among the new schools of the burgeoning West. Ohio's Oberlin College went coed in 1837, four years after its founding. The University of Iowa became the first state school to accept women, in 1855, and most other public university systems followed suit over the next 20 years.

Bascom started at the University of Wisconsin at age 15. She didn't set out to be a scientist, and her first degrees were in the humanities. So, how did she discover geology? One story suggests it was during a visit to Mammoth Cave with her father. Another tale has her riding in a carriage with her father and a geology professor colleague of his who began explaining certain attributes of the passing landscape, and her curiosity was piqued. In any event, she would later proclaim geology as "the most important of the sciences … and really the culmination of all sciences."

After completing her master's degree, she spent two years teaching at Illinois' Rockford College (today, Rockford University), but the facilities were lackluster and the teaching load wearying—she led classes in everything from algebra to zoology to Bible studies. Bascom yearned to plunge back into geology and set her sights on Hopkins. She knew it was a long shot, going so far as to write a letter to Gilman acknowledging that admitting women "is not usual" at his school but that she had no choice. "It is because I have found the opportunity for petrographical work so limited in accessible institutions that I turn to Johns Hopkins," she explained.

The question—whether to admit women—had been on Gilman's mind. Indeed, before the school opened, he consulted with several influential academic leaders, including Charles William Eliot, president of Harvard, who was "foursquare opposed to the idea of admitting women into American universities," Benson says.

In the 1890s, as schools like Yale, Brown, and Columbia opened their graduate programs to women, Hopkins continued to hold no official policy toward women seeking advanced degrees. Notes from a coeducation-focused gathering of Hopkins trustees back in 1876 state that the university "was not prepared to commit itself definitely to any course but would leave the whole subject … in the hands of the President." In essence, the admission of women would be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, with Gilman getting the final say. "Failure to confront the issue of coeducation head-on was characteristic of the Trustees and President for years to come," writes Julia Morgan in Women at the Johns Hopkins University: A History. The murky, shifting rules basically said women could consult with professors and sit for exams but were barred from taking most classes and lectures. And while it might seem a sweet deal that they wouldn't be charged tuition, this meant women weren't eligible for fellowships or stipends and were effectively kept off the official registry.

The situation was far different over in East Baltimore, where the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine was coeducational at the time of its 1893 ribbon cutting. All the paternalistic handwringing about women being too delicate for the rough-and-tumble world of manly academics dissipated when cash entered the equation. The B&O Railroad stock that businessman-cum-philanthropist Johns Hopkins had left in his will to fund the medical school plummeted in value in 1888, threatening to substantially delay the school's completion. Four daughters of Hopkins trustees—M. Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Elizabeth King, and Mary Gwinn—formed a fundraising women's committee pledging to raise $500,000 for the school if, and only if, women were admitted on an equal basis with men. The deal was accepted, and when this undertaking stalled with less than half the money raised, Elizabeth Garrett stepped up to personally pledge the more than $300,000 needed to meet the goal.

The medical school's 1893 inaugural class of 18 included three women. Writer Gertrude Stein was admitted in 1897 (though she didn't take a degree), and Florence Sabin graduated in 1900, later becoming the school's first woman professor and a leader in the study of tuberculosis.

While Bascom was the first woman to receive a Hopkins PhD, she wasn't the first to complete the requirements to earn one. That distinction belongs to [Christine Ladd]9https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-devastating-logic-of-christine-ladd-franklin1/), who endeavored to get a doctorate in mathematics in 1878. She was, over time, permitted to attend the necessary classes and eventually wrote a dissertation described as "brilliant" by her professors. But she was not awarded the doctorate her work had earned her. Well, not until 1926. During the school's 50th anniversary celebrations, a 79-year-old Ladd was finally handed her degree.

Bascom started at Hopkins under the same cloud of uncertainty previous women had endured. Her pseudo-admission (she was not officially in the books) was provisional and subject to periodic reevaluation. While she was allowed to take the necessary classes and labs, there was no guarantee that a degree was waiting for her at the end of it all. Given all she had to deal with, it's a small mercy, then, that the one gross indignity Bascom was said to have endured while at Hopkins might not have occurred. On websites and in articles and books discussing her, it is often stated that she was required to sit behind a screen or curtain during classes to segregate her from the men. "I am about 95% certain it did not happen," retired Sheridan Libraries senior reference archivist Jim Stimpert wrote in an email. Part of Stimpert's job had been checking the accuracy of Hopkins-related Wikipedia pages, and when he saw the screen story on Bascom's entry (without a citation), he began an exhaustive search for corroborating documentation, not only in Hopkins' records but also in the archives at Smith College, home of the bulk of Bascom's papers. Nothing was ever found to substantiate the story. Stimpert feels some of the men who witnessed such a screen would have written about it at some point, to say nothing of Bascom herself.

"Bascom was a very outspoken person with strong opinions, especially in her later years, and she did not suffer fools gladly," Stimpert concludes. "As a major figure in geology in the early 20th century, she would have had the perfect platform to comment on and criticize Hopkins for its alleged actions."

While the administration fretted about its petticoated student, geology professor and noted petrologist George Huntington Williams became Bascom's trusted mentor, treating her like any other budding geologist. Well, except on at least one occasion when he wanted to do fieldwork with her. Realizing the mores of the day would frown upon the pair of them being alone out in the boonies, he asked his wife to come along as chaperone. Bascom's dissertation, The Ancient Rocks of South Mountain, Pennsylvania (still viewable on the USGS website), used a combination of fieldwork and petrography to reclassify certain rocks long thought to be sedimentary as volcanic in origin.

"She was an astute and careful scientist and her geological descriptions have stood the test of time—relevant and useful to this day," says geologist Bruce Marsh, professor emeritus in the Johns Hopkins Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. "As a thorough geologist, she also understood soils and erosion, how rivers form, and how landscapes are shaped in what we call geological morphology. She was a real scholar and a first-class scientist." Marsh adds that the rocks she worked on "were very difficult in those days to understand." Indeed, Bascom would not have known about the ancient volcanic forces that created the rocks she examined and reclassified—the Proterozoic cataclysms described in this story's opening. The scientific field of plate tectonics wouldn't come into its own until the 1960s. But Bascom's foundational work in petrology moved the science along from the naked-eye observations geologists had relied on.

It must have been sweet relief in January 1893 when Gilman called Bascom into his office to tell her she would be granted a PhD at the end of her studies. During Commencement ceremonies that June on the stage of Baltimore's long-demolished Academy of Music, a roar of applause erupted when Bascom's name was called. But she wasn't on hand to hear it, having elected to skip Commencement and head off to a teaching job at Ohio State.

While Hopkins didn't go out of its way to publicize its newly minted lady PhD, the national press jumped on the story. The Milwaukee Journal's coverage of Bascom's singular accomplishment ran under the headline "She's a Wisconsin Girl." The otherwise laudatory story includes this passage: "In appearance, Miss Bascom is of medium height, rather inclined to stoop. She is a pronounced blonde and while she cannot be classed as a beauty her features are attractive and pleasing." It's hard to imagine this sort of wordage appearing beneath a "He's a Wisconsin Boy" headline.

Bascom might have cracked open the graduate-study door, but there was no steady stream of applicants behind her. Hopkins wouldn't hand another woman a PhD until 1911, when four women received doctorates. Ira Remsen, who followed Gilman into the university president's chair in 1901, had officially opened Hopkins' advanced degree programs to women four years earlier, saying it was a matter of "justice and common sense."

Bascom taught at Ohio State for two years before moving to Bryn Mawr (where M. Carey Thomas was president) and creating its Geology Department. She amassed an impressive collection of rocks and mineral specimens that students still handle and learn from today. By 1937, the U.S. Geological Survey employed 11 women geologists, eight of whom had been taught by Bascom at Bryn Mawr. But beyond being a geology professor, Bascom had always wanted to be a working geologist, and so in 1896 she began a long and fruitful relationship with the USGS, a scientific branch of the Department of the Interior billing itself as "the nation's largest water, earth, and biological science and civilian mapping agency." Whereas other professors might have enjoyed summers off, she spent hers slogging through sections of rural Pennsylvania and Delaware, exploring railroad cuts, outcroppings, stream banks, and other areas of exposed rock. She would then analyze samples and complete her maps over the winter.

In honor of her decades of work, the regional branch of the USGS based in Reston, Virginia, became the Florence Bascom Geoscience Center in 2018. "We didn't just pick Bascom's name because she was a famous first woman at USGS but because she was intrinsically tied to our science center in terms of its mission and the products and the science that we still do today," says Peter Chirico, the center's associate director. "We do geologic mapping of the Mid-Atlantic Piedmont region, just like she did. We employ new geophysical techniques, and she was a pioneer in adapting and using new methods of classifying rocks such as petrography."

Indeed, Bascom never stopped keeping abreast of the latest scientific approaches to identifying and classifying rocks. In 1906, she spent a sabbatical year at Heidelberg University in Germany learning the latest in crystallography, the examination and measurement of mineral crystals, from the pioneer of the science, Victor Mordechai Goldschmidt. Chirico wonders if "being a woman in a field that was literally all men" might have spurred her on to always stay on the cutting edge. "She was probably questioned more than her contemporaries as to her interpretations, and I think her pioneering use of technology was a way of quantifying her observations—she had to come up with evidence, scientific evidence for what she thought," he says.

Away from the lecture hall, lab, or field, Bascom's paper trail doesn't include a whole lot about her personal life. Her love of geology was perhaps only matched by her love of animals. She was an accomplished equestrian who sometimes took to the saddle to perform her fieldwork. Bascom never married or had children, and though a firm taskmaster with her students, she was apparently an indulgent companion to a series of beloved dogs. A failing memory forced her into retirement in 1940; she died five years later and is buried in the family plot in the Williams College Cemetery.

Her name lives on in some out-of-this-world places: Both an asteroid and a crater on Venus are named after her. Closer to home, the Johns Hopkins Homewood building for undergraduate research became the Florence Bascom Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories last fall. "Florence Bascom's legacy as an educator and a researcher will continue to live on, through countless students who use these labs and the faculty and postdocs who teach in them," President Ron Daniels said at the renaming.

Bascom's photo hangs in Olin Hall, home to the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. It shows her with one of her dogs and includes a bit of her colorful mapping work showing delineated rock layers. Bruce Marsh says there is another Bascom artifact that he used to put on display—a letter from Charles William Eliot, Harvard's coeducation critic. While Marsh says he can't bring himself to put it out anymore because it's "embarrassing," the missive speaks volumes about the shortsightedness of those who wanted to keep women out of the classroom.

"Eliot wrote a letter to our department," Marsh says. "He said in giving [Florence Bascom] a PhD, you have forever defaced the PhD in the eyes of the world."

Today, our eyes roll in response.

Posted in Science+Technology