In the spring of 2022, just four weeks after the Russian invasion, Peter Pomerantsev returned to his birthplace of Kyiv, Ukraine. An expert on disinformation and propaganda, the SNF Agora Institute senior fellow sought to record Russian atrocities in the region, lest the truth be forgotten or manipulated. Pomerantsev was already working on his third book at the time, a biography about World War II–era propagandist Sefton Delmer. As his historical research mixed with modern concerns, the author wove what he was seeing into Delmer's story.

How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler provides a surprisingly timely message for a book so deeply rooted in history. During World War II, both Nazi and British forces invented new forms of propaganda and disinformation, caught in an arms race that paralleled the one on the battlefield. Delmer, a German-born British journalist who had gotten to know Hitler up close, was a key figure in this "information war." He found that the population of Nazi Germany was steadfast in its ways, unswayed by appeals to peace or human welfare, unwilling to consider facts that their leaders denied. As a result, Delmer was forced to get creative. The Germans would only hear what they wanted to hear. So why not give it to them?

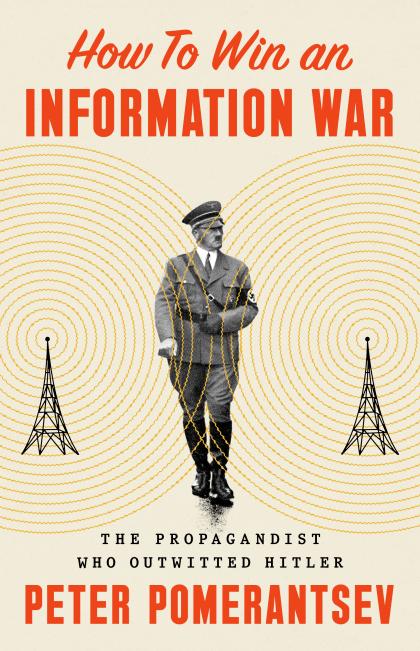

Image credit: Hachette Book Group

Under Delmer's guidance, British intelligence broadcast years of influential radio programs across the channel and into enemy homes. Der Chef was one such initiative. Sometimes raunchy, always vulgar, the program was hosted by a German man known only by the show's name. At first listen, his rants seemed in line with Nazi ideology, praising the German people before devolving into racial slurs and antisemetic rhetoric. But the host's anger did not stop there. According to der Chef (who was really a Jewish actor in Aspley Guise, England), the Nazi Party was full of secret Bolsheviks who stuffed their own pockets while the German people suffered. Every bit of fear and disgust felt toward foreigners and Jewish people could be turned back around to target the Nazis' own leadership. And while the broadcasts told plenty of exaggerations and lies, many of its most powerful moments came from telling the truth. Corrupt officials were called out by name. Massacred soldiers were mourned as martyrs. For every made-up story about gross incompetence and sexual perversion, real faults with the party were exposed, giving the program reputability.

German listeners were fascinated by the show and intrigued by its mysterious host. Who could know all these things, they wondered, except for some high-ranking military insider? After all, would the British really air something so explicitly pro-German?

As World War II carried on, Delmer's methods expanded. His men and women dropped newspapers from the sky, sent fake letters to the families of dead German soldiers, and, of course, launched several more radio programs. Propaganda was evolving, and Delmer was leading the charge.

Details of Delmer's story may feel familiar to the modern reader. On another trip to Ukraine in April 2022, Pomerantsev found himself among a group of American journalists interviewing President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. The Ukrainian leader shared his belief that everyday Russians were in an "informational bunker," unwilling to accept the realities of the war. This concern would become one of the central questions of Pomerantsev's book: How do you influence someone who doesn't want to listen?

In this excerpt from How to Win an Information War, Pomerantsev describes how Delmer helped deflate the German spirit in the lead-up to D-Day. The effort required collaboration from all corners of Britain's propaganda arm, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE), which brought repurposed artists like the German-born René Halkett and Isabel Rawsthorne (Delmer's wife) together with seasoned propagandists like Delmer himself. Mentioned here are stations used by Delmer and the PWE, including Christ the King, which was targeted at German Catholics, and the Sender (short for Sender der europäischen Revolution), which was co-run by exiled German Socialists. All groups and efforts came together to help the Allies deal their most important blow yet.

If these "dead letters" made Delmer feel ashamed, Nachrichten für die Truppen, his largest D-Day project, was "of all the enterprises I launched during the war . . . the one of which I am the proudest." Bruce Lockhart called it the PWE's "most ambitious achievement in the war."

Nachrichten was a daily newspaper. A team of twenty-five American and British editors and journalists worked on it in a barrack rapidly constructed by Milton Bryant (MB). Production started at 11:00 p.m., when the editors took the latest Sender broadcasts, adapted them for text, added photos and maps, and included specially written columns. Halkett was in charge of the German copy. Isabel worked on the layout, photos, and illustrations. At 3:00 a.m. a female dispatch rider would motorcycle the proofs to Delmer's rooms and wake him. The telephone in the editing suite would soon ring with Delmer shouting changes, which were then fixed before the copy was sent to be printed, guillotined, and packed into laminated-wax, sixty-inch packages. At 6:00 p.m., US Army trucks picked up the copies and drove the newspapers to Cheddington, home to the US Leaflet Bombers. At a height of a thousand feet a fuse burned the container, and the printed materials fluttered down, nine thousand leaflets to a bomb, over an area of just one square mile, so by nighttime hundreds of thousands of copies of Nachrichten were over enemy lines, ready to be read by German soldiers in the morning, often earlier than the Nazi newspapers. This was one of the most dangerous news runs in history.

Image credit: Getty Images

In French fields and roadsides, German soldiers picked up the newspaper that had just dropped from the sky. They knew perfectly well it wasn't German. Unlike the Sender, it used neutral language: German troops were not "ours" but were defined by their army and squadron number. The Nachrichten took no sides, just matter-of-factly reinforced how the German army was losing, implying that the leadership had lost its way and it was time to think about self-preservation, not self-sacrifice. It calmly informed the reader that the Americans were supplying the Russians with new armor-piercing bombs, that the police in occupied France were so impotent they were unable to locate murderers on the loose, that the number of German soldiers deserting to neutral territories was growing, and that some were even sending food parcels back home.

With D-Day nearing, the tenor of the radio shows rose. On Christ the King, Father Elmar railed against the arrest of Catholic Austrian cardinals by the Vienna SS, urging his listeners to tear out of their hearts "the poison of National-Socialism which makes blind and insensible against injustice and misery." He no longer disguised his desire for Austrian independence: "We Austrians long for the day when we can live again as free citizens in a free land."

On Short Wave 30.7, there was something new. The program opened with "SSKGY, the SS Battle Group York." And then came the presenter: an SS man who was sick of Himmler and of the party, and was leading a rebel SS cell in Poland. The presenter was Hans Zech-Nenntwich, who had served in the SS in Poland, where he had supplied arms to the Polish resistance, which in turn helped him escape to England. That part of the story was corroborated. The rest was uncertain: ZechNenntwich claimed he was part of an internal SS resistance cell. Delmer had no idea if it was true. Halkett thought the story nonsense. But Zech-Nenntwich was useful for all the latest SS gossip and the latest SS slang.

Over on the Sender, Vicki's concerts were becoming ever more elaborate: "We began to manufacture whole troop concerts. Pretending that our songs and sketches were performed by soldiers and nurses at the front, we acted and sang them ourselves in the most endearing and amateurish way. One of our soldiers even managed to fall into the drum with a resounding crash on his way up onto the stage."

In the weeks leading up to D-Day, the news on the Sender was giving ever more details about petrol and supply shortages for the army, about how all the best kit was being given to the Eastern Front, and about how General Rommel was coming up with a clearly absurd and desperate plan to attack England with gliders. The news was rife with examples of almost casual desertion, sabotage, and insubordination.

In Dresden, Victor Klemperer heard more rumors about demoralization in the army, along with grumblings of revolt:

_Over Whitsun the Windes visited their navy twins in Swinemünde. Frau Winde said: "It" would start in the navy, as in 1918. Unpopular officers had been thrashed. Emergency slaughtering of livestock was now being carried out on a large scale, food for the winter was no longer assured, the government was staking everything it had.

Rising in the morning of June 6, Halkett came out on the lawn behind the house and heard an enormous noise. Looking up, as far as he could see, covering the whole horizon, were airplanes flying in one direction. One of 58 | the planes let forth a burst of gunfire, and a lot of tracer bullets came down. It was a gunner trying out his machine gun. The invasion had started.

For listeners across Europe, the Sender was the first radio to break the story of the landings, reporting on them at 4:50 a.m. while Goebbels's radio still slumbered: "The enemy is landing with force from the air and from the sea. The Atlantic Wall is penetrated in several places."

The leaflet bombers were already delivering the latest Nachrichten. A million copies had been printed specially for D-Day. "Armour penetrates deep into the interior," went the headline; "there are reports of bitter fighting with parachute commandoes in Normandy and the Mouth of the Seine."'

The mention of the "Mouth of the Seine" was a piece of deception, helping the Allies distract from the Normandy focus of the invasion. The other article on the front page of the Nachrichten was about an impending Soviet offensive, which casually mentioned that the head of the German general staff was currently visiting the Eastern Front: the soldier on the Western Front was meant to infer that the East was Berlin's priority and he was being abandoned to the Allied onslaught.

The mood at Woburn, Delmer felt, was a little subdued. As the German POWs and émigré newsreaders gathered for programs the week of D-Day, Delmer thought he could detect that despite their desire for Hitler's Germany to perish, despite the risks of Nazi retribution against them and their families, there was also among them a secret, often subconscious sympathy and sadness with which these men now watched their countrymen across the channel being bludgeoned into extinction. … Not for nothing had we immersed ourselves so completely in the life and surroundings of our Wehrmacht listeners. We were able to feel those cannonades as though they were coming down on our own heads, and the talks which my speakers now put out reflected this. They had in them an undertone of personal tragedy which made these ephemeral pieces of psychological warfare as moving for me to listen to as if they had been the greatest literature.

The first D-Day broadcasts spoke of how: the will to sacrifice on the part of our men and our navy was extraordinary. One torpedo flotilla against large destroyer groups. Of course one can't expect success from such proportions. You get the feeling that if our men shoot down one enemy bomber, there are many more coming right behind. In the area between Le Havre and Cherbourg the enemy has landed, they were able to land tanks and armed cars, it will be pretty difficult for our infantry to cope with all this.

To Delmer's ears, Halkett's speech was the best of the lot. He delivered it in the staccato rhythm of a Prussian officer, as 1.5 million leaflets fluttered down onto German troops urging surrender:

This is a report, an epitaph, a warning. It is a warning to all of those who may be lying in an outpost somewhere on the beaches, or are stationed somewhere up on a hill, or on the coast. And as they lie there they may get the order, "Hold on, the reinforcements are on their way to you."

The reinforcements will not come. They cannot come because nothing is being done about sending reinforcements, because all these men have been written off—written off as dead and lost.

Here is the warning story which the few survivors of the 716th Infantry Division have brought back with them. On Tuesday came the first attack on the coast. The division got the order "hold on, reinforcements are on the way." By Thursday for all practical purposes the division was surrounded and overrun. In its rear were the enemy parachutists. In front lay the enemy battlecruisers firing at them, hacking their concrete dugouts to shreds. Overhead in the sky, a thick curtain of enemy aircraft. They drop a never-ending barrage of bombs and explode what is left of the minefields. Far and wide not so much as a single German fighter. But an order did get through at last from the Command: "Hold Out. Hold out to the last round of ammunition."

Halkett paused for a moment for the senselessness of the order to sink in. Then he went on:

There they lay in their smashed and slit up dugouts, naked, without cover. Grenadiers with pistols and machine guns and anti-tank guns. Guns which they were never to get a chance to fire.

After another pause,

That was literally all that was done for the 716th Infantry Division. Left behind to be overrun and rubbed out were 4,000 men, 4,000 comrades left in the trap, defenseless, deserted, without cover or help. In front of them on the water lay the enemy battleships.

Those enemy battleships had fun with a little target practice against our fortification and our boys. That was the end of a division. The end of comrades who held out and waited for reinforcements or relief. Who did not know they had been written off—written off from the very beginning.

Delmer thought that it was a "brilliant performance" and that behind it was genuine "misery and bitterness" in Halkett's voice. Part of it, Delmer judged, may have been conscious acting. But most of it he thought was genuinely felt—the resentment and sorrow of an officer seeing his fellow countrymen laying down their lives for a regime of criminals and cranks.

In the interviews about his life recorded decades later, Halkett never quite confirmed or denied whether he had any genuine feelings during his speech or whether he had been purely "putting it on," as with the earlier talk that his co-host Sepp had fallen for. But he resented how Delmer had reduced him to something of a caricature: a Prussian officer with German sympathies, "an actor owned by the character he performed." One can understand Halkett's frustration at being made a mere character in someone else's story. He was an artist. He'd acted on the stage professionally. He was one of the creative forces at Woburn: co-author of the malingerers' handbook, co-editor and lead writer of Nachrichten, always innovating on the radio shows. He was an author, not someone else's sketch. And who was Delmer to define when he was genuine and when he was acting? Who was Delmer to define what reality was, what the truth was, in the first place?

Excerpted from How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler (Hachette Book Group, 2024)

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged world war ii, snf agora institute