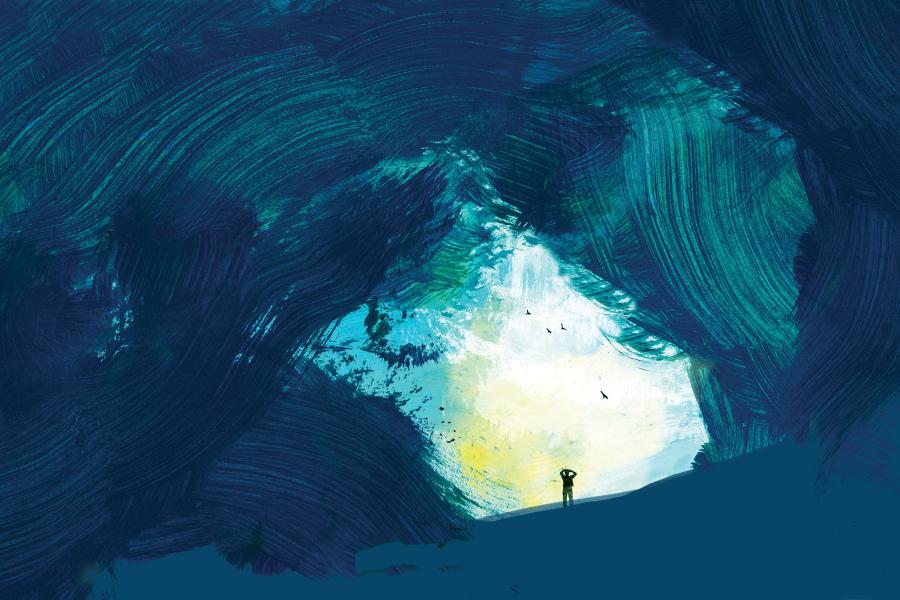

I'm staring at a stunning, rainbow-sherbet sunset. In a nearby stand of evergreens, a choir of crickets chirps in unison. Fireflies flicker above the rocks I'm sitting on, a promontory in the middle of a gently flowing river. From my vantage point, I can't see David Yaden, a Johns Hopkins professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, but I can hear him. He has a few questions about how this tranquil scene is making me feel.

Would I say that time has slowed? (A little.) Did my sense of self seem diminished? (Kind of.) Could I feel a connection with all living things? (Not really.) Had my jaw dropped? (It sure had!)

Yaden finishes his questions, and the sunset disappears. Now, instead of the dusky landscape I see a teal green backdrop and the words "connect to Wi-Fi."

I remove the virtual reality headset and I'm back in a room at the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, on a couch where patients take part in studies that investigate the use of psilocybin—the compound found in so-called magic mushrooms—in the treatment of everything from Alzheimer's disease to depression. Sitting across from me in a leather recliner, Yaden explains that for a few years now, he and Albert Garcia-Romeu, a fellow professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who studies psilocybin as an aid in the treatment of addiction, have been asking patients at the tail end of their psychedelic experience to explore a handful of virtual reality settings and describe the feelings each one evokes. The survey Yaden gave me while I admired that technicolor sunset had been driving toward one central question: Was I experiencing awe?

Image credit: Stewart Watson / Getty

That's because awe—the hair-raising, goose- bumps-inducing sensation you get staring at the ocean or sitting center row at the orchestra, the one that knocks you momentarily loose from the ordinary and forces you to reconsider your understanding of the world and your place in it—is a big part of what makes a psychedelic experience so powerful. Previous research has suggested that, by provoking profound, mind-expanding awe, psychedelics can reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and addiction.

For now, Yaden and Garcia-Romeu are simply trying to suss out whether mixing psychedelics and VR is safe. But they also wonder if by doubling up on awe, or "by giving people a drug and then putting them in an awe-inducing environment," says Garcia-Romeu, "we could potentially turn the gain up."

The tricky thing about emotions is they're difficult to measure; no one feels 87% happy or 15 kilograms of sadness. A decade ago, scientists measured awe by asking people, simply, if they felt it. The problem with that, according to Yaden, is that "different people have different definitions of the emotion."

So, Yaden assembled a team of researchers to develop a robust way to measure awe.

First, the team scoured previous scientific studies to come up with six core characteristics of the emotion: self-diminishment, time alteration, physical sensations like chills, and a feeling of connectedness, as well as the perception of vastness and the struggle to comprehend it.

Then they recruited more than 1,100 people to write about a recent experience of "intense awe." Some wrote about the outdoors, recalling the first time they saw the Rocky Mountains, or the sight of a lake in deep winter, glistening with ice. Others wrote about watching their children play a musical instrument, or public figures deliver inspirational speeches, like Elon Musk detailing plans to send humans to Mars.

Afterward, participants answered questions that the researchers had created based on the six facets of awe, indicating how much they agreed with statements like, "I felt my sense of time change" and "I felt I was in the presence of something grand."

In the end, Yaden and his collaborators developed a 30-item questionnaire that doesn't just statistically and reliably measure how much awe a person feels but also "captures the full depth and breadth of the awe experience," they wrote in their 2018 paper, published in The Journal of Positive Psychology. As awe increasingly becomes a target for academic studies worldwide, the Awe Experience Scale could play a pivotal role. Researchers have already begun putting it to use, translating it into other languages and incorporating it into studies on awe in nature, meditation, museums, and, of course, VR. That research is revealing the physical and emotional benefits of awe, no psychedelics required.

Awe has gone by a number of names. Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant both wrote about the sublime, while Charles Darwin expounded on wonder. Abraham Maslow introduced the idea of "peak experiences," which he described as "exciting, oceanic, deeply moving, exhilarating, elevating," which is to say: awesome.

Yet, in the early 1990s, when influential psychologist Paul Ekman identified the six basic human emotions (joy, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, and surprise), awe was not on the list. It was one of Ekman's students, Dacher Keltner, who brought awe into the scientific conversation.

Keltner, a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life (Penguin Press, January 2023), says he was immersed in awe from a young age, at art museums and on camping trips with his parents. "My dad is a visual artist. My mom taught Romanticism and poetry. I grew up at a really wild time, in Laurel Canyon in the 1960s. So I was always walking around just kind of awe-struck."

During his postdoc years, which he spent at the University of California, San Francisco, studying under Ekman, Keltner had a realization: "Almost everything that humans care about—religion, art, music, big ideas, taking care of young children—awe is close to it. Awe is always close to really important stuff," he says. "I thought, let's study this emotion and figure it out."

In a seminal 2003 paper, Keltner partnered with University of Virginia psychology Professor Jonathan Haidt to nail down a prototypical definition of awe. The pair studied depictions of awe as it was represented in literature and scholarly thought, from the Bible and Bhagavad-Gita to the writings of sociologists Émile Durkheim and Max Weber. In doing so, they identified the two key features of awe: a sense of vastness and a momentary inability to process it. Importantly, they noted that vastness could be physical, such as looking up at a cascading waterfall, or cognitive, like the vertigo you get when you think about something intricate or incomprehensibly large—photosynthesis, say, or the size of the solar system.

Keltner and Haidt also took a guess as to how awe evolved, theorizing that the reverence we feel in the presence of a powerful leader played a role in maintaining social hierarchy and cohesion in early human societies. Later, Yaden and Italian researcher Alice Chirico suggested that awe developed as a way for humans to identify safe refuges. High vantage points with large vistas, for example, would have allowed them to see predators approaching.

In the conclusion of their 2003 paper, Keltner and Haidt laid out a research agenda to guide future awe scientists. "There is a clear need to map the markers of awe," they wrote. Fifteen years later, Keltner was on the research team that helped develop the Awe Experience Scale.

In the meantime, the science of awe has proliferated. Research has shown that people who feel awe more often report higher rates of satisfaction with life and greater feelings of well-being. Awe can help us be less stressed, less materialistic, and less isolated. There's evidence that awe is good for our physical health, too; one study reported that people who experienced the emotion more often had lower levels of cytokines, the proteins that cause inflammation. Awe might also contribute to a more harmonious society. When researchers exposed one group of study participants to an awe-inspiring view of towering eucalyptus trees, and another group to a neutral scene of a building, those who admired the pretty view were more likely to help a stranger pick up something they had dropped afterward. Another study found that awe made people less aggressive.

While science has gotten good at identifying the external manifestations of awe, researchers are still working to untangle what's happening inside the body.

"That's the big holy grail, the big mystery," Keltner says. "When people feel awe, it's almost an oceanic sense of, 'I'm a part of something really big.' How does the brain represent that? We don't know."

We do have a few hints. There's evidence that awe deactivates what's called the default mode network—the part of the brain associated with self-perception—allowing us to step outside our insular thoughts and ruminations and be wholly present in the moment. Awe also activates the vagus nerves, a braid of nerves running from the brain to the large intestines that is associated with feelings of compassion and altruism. In short, the emotion turns our focus away from ourselves, "providing connectedness and perspective," Yaden says. "Suddenly, our problems no longer feel as big and daunting."

In order for scientists to develop a more nuanced understanding of the chemical and physiological changes that happen inside an awestruck person, Yaden hopes to see researchers step outside the laboratory. To date, many studies about awe have involved showing participants videos—nature documentaries or footage of tall trees swaying in a forest—a method Yaden fears may not be all that effective in inspiring pure, unadulterated awe.

"If we're studying awe, I think we need to make sure that we are eliciting sufficiently intense experiences to have an effect," Yaden says. In other words, watching a video montage of the Grand Canyon might provoke a sense of wonder, for example, but actually standing on the rim, looking down into the expanse, is more likely to trigger true chills-up-the-spine awe. However, when it comes to studying the interface of awe and psychedelics, as Yaden and Garcia-Romeu are interested in doing, getting patients out of a clinical setting can be a challenge. "The lawyers won't let us take people outside when they're under the influence," Garcia-Romeu says, "so we kind of see VR as a backdoor to doing that."

The scientists plan to spend another year or so slipping the VR headset on patients dosed with psilocybin to learn what settings might dial up the awe of a psychedelic experience. It's just the first step toward using awe as a therapeutic intervention, but Yaden sees potential. "It's an area really rich for research," he says.

While they were working to produce the Awe Experience Scale, Yaden and the research team asked participants to identify the specific trigger of their awe experience. Natural beauty was far and away the top response; more than a third of participants said it was the source of their awe. Notably, the second most popular trigger was a write-in category, and a significant number of responses named childbirth as a source of profound awe.

Two months ago, Yaden watched his wife give birth, calling it the most awe-inspiring moment of his life. Lately, he's enjoyed watching his newborn son experience amazement.

"Right now it's the sky. We take him to the window and his eyes just pop."

Yaden says he seeks out "little doses" of awe for himself every day—morning walks by the Inner Harbor, for example. "Part of what's enjoyable about that is the vastness, just looking out across the water."

In a study to determine what causes people to feel awe, Keltner and a research team gathered narratives about the emotion from 26 countries around the world. "Write about a time your mind was blown," he and his collaborators instructed. Using these accounts, Keltner developed what he calls the eight wonders of life: moral beauty, nature, collective movement, music, art, spirituality, big ideas, and mortality. Incorporating these wonders into your life to experience awe is "strikingly easy," Keltner says. In fact, you're probably already doing it.

Image credit: Klikk / Getty

"Most people experience awe pretty regularly," echoes Yaden. "Most vacations include awe excursions. People climb to the top of mountains, they go to museums, they visit monuments."

Keltner says there's a misconception that awe is rare, but research shows "it's actually kind of common. Most people feel it two to three times a week."

Another misconception about awe is that you can't orchestrate it. "It's like, dude, have you ever bought concert tickets?" Keltner says jokingly. "Did planning that event ruin your experience of awe? No. You can find it, and you can plan for it."

Want more awe in your life? Listen to a piece of music that gives you the chills. Think of someone who inspires you. Drive, hike, or bike to the prettiest view in your neighborhood. Go sing with other people; go move in unison with other people. As you do, Keltner says, "Pause. Clear your mind. Be open."

Encouragingly, research has also indicated that finding awe might not even require leaving your home. In a recent study, Yaden and Marianna Graziosi, a doctoral candidate at Hofstra University, asked participants to recall a time they were in awe of a loved one. One person wrote about his wife receiving a terminal diagnosis with startling grace; another recounted hearing their mother describe a painful childhood.

By using the Awe Experience Scale, Yaden and Graziosi were able to determine that the feelings evoked by those closest to us meet the widely accepted definition of awe.

They concluded: "Perhaps awe, while an ordinary response to the extraordinary, is also an extraordinary response to the ordinary."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged psychology, psychiatry, behavioral sciences