Earth as we know it offers majestic trees, meandering streams, and rolling hills. Yet below the Earth's surface, forces and elements like intense pressure and scalding magma simmer and stew—and make possible the idyllic planet, nestled in the safety net of the atmosphere, we call home.

In What's Hidden Inside Planets?, published last month by Johns Hopkins University Press as part of the Wavelengths book series, planetary geophysicist Sabine Stanley, with help from science journalist John Wenz, guides readers through the inner workings of planets in and beyond our solar system. Stanley is the ultimate tour guide, given her roles as a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and the Space Exploration Sector at the Applied Physics Lab, and as a scientist on NASA's InSight mission investigating Mars' ancient magnetic field. In her new book, she weaves in stories from her life with science from her field. The result is a story that readers both within and outside of planetary science can relate to and enjoy.

Image caption: Textile artist Dolores Miller (left) with planetary scientist Sabine Stanley (right)

With the release of Stanley's book comes the opening of a traveling art exhibition, Fierce Planets, that features textile art inspired by the scientist's work. The exhibition stems from a partnership among Hopkins Press, the Johns Hopkins Office of Research, and a global arts organization, Studio Art Quilt Associates (SAQA), based in Massachusetts. Nearly 200 works of fiber art submitted by artists from around the world showcase aspects of Stanley's research, and 42 of those pieces were selected to be part of the exhibit, which opened last week at the Exploratorium in San Francisco and will move to other locations across the country—and perhaps the world—over the next two years.

"These textile art pieces [are] a wonderful vehicle to communicate my work in science and inspire people to seek to understand the importance of the processes that happen inside Earth and the other planets," Stanley says. "For this, I am eternally grateful to the artists [who] created them."

Making science personal

"It was 2 a.m. on a summer night," Stanley writes in the book's opening pages. "I had just arrived home from a night out with friends when I stepped out of my car and my jaw dropped. The dark sky was lit up with vibrant green flashes, and I stared, mesmerized, at the elegant motions. This was my first time seeing the 'northern lights' of the aurora borealis in person."

From this first-person beginning, Stanley transitions seamlessly to science, explaining that the eerie green lights of the aurora are created by the "interplay between the Sun, 94 million miles away from us, and Earth's molten iron core, 1,800 miles beneath our feet. It's in the core that Earth's magnetic field is generated, and this is crucial to the creation of auroras, which hover anywhere from 60 to 600 miles above our surface in the ionosphere."

In this excerpt, and throughout the book, Stanley's writing style differs from the dozens of articles she's published in academic journals. The personal narrative-based approach is intentional—and core to Wavelengths, launched in 2021 to bring the discoveries of leading interdisciplinary scholars to readers interested in learning more about science.

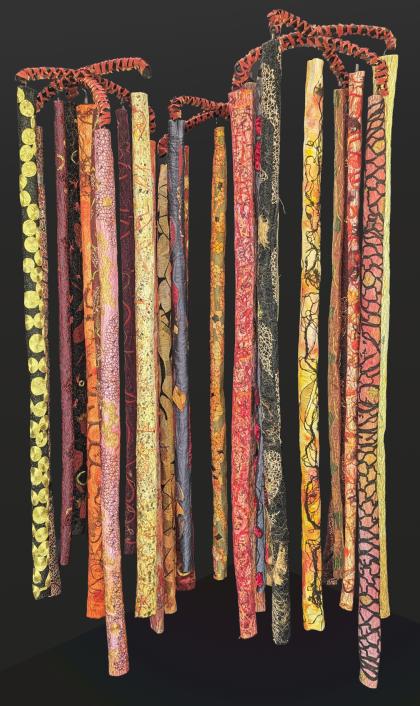

Image caption: A detail of Pale Blue Dot 2, a work of fiber art created by Dolores Miller for Fierce Planets

"There are so many educated professionals and individuals who are curious about the world and realize they know very little about, for example, the inside of planets," says Barbara Kline Pope, the executive director of Hopkins Press. "Wavelengths books, written in a style similar to articles in The Atlantic magazine, are created with this audience in mind." As paperbacks, the books are designed to be lightweight and portable, and those who prefer reading online can download an e-book version for free from Project MUSE, a massive online aggregation of journals and books created in 1995 by a partnership between Johns Hopkins University Press and the university's Milton S. Eisenhower Library. Since 2021, readers in more than 100 countries have accessed Wavelengths books this way.

What's Hidden Inside Planets? is the sixth book in the Wavelengths series. Other books in the series, each written by a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins, paired with a science writer, explore artificial intelligence, obesity, cancer, health disparities, and sustainability. A seventh book, What If Fungi Win?, is forthcoming this spring from Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist and immunologist with joint appointments in the Bloomberg School of Public Health and the School of Medicine.

"Engaging the public in science and communicating the evidence supporting it are important because, in many cases, science affects and informs how people live their lives," Pope says. "What makes science communication and engagement even more critical at this moment in time are the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation, and the severe polarization related to any number of science-related issues."

Often, science papers in academic journals use discipline-specific language and jargon that outside audiences may struggle to decipher. The goal of the Wavelengths book series, Pope says, is to use personal narrative to create an interesting, thought-provoking story. "The science of science communication demonstrates that people process and remember information more readily when it's part of a narrative," Pope explains. "A narrative-based approach, then, is more effective than throwing out statistics and expecting that information to stick."

When science inspires art

From the astronomy depicted in ancient Egyptian art to the anatomy infused in Renaissance paintings, scientists have long influenced artists. Today's scientists are no exception. When Stanley delivered a virtual presentation to hundreds of textile artists this past summer, the artists used what they learned to create new works as part of a call for entries by SAQA and the Johns Hopkins University Press and Office of Research.

The response exceeded expectations, resulting in the traveling art exhibit, Fierce Planets, featuring 42 (or just under one-fifth) of the submissions. The exhibit opened last week, with limited art on display, in San Francisco. In the spring, it will open at the Louisiana State University Museum of Art in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, before moving to the Dunedin Fine Art Center in Dunedin, Florida, in the summer of 2025.

Planning for exhibitions at other venues is underway, says Anna Marlis Burgard, who serves as the director of strategic engagement (and director of the Wavelengths science communication program) at Johns Hopkins, where she develops books, media campaigns, and partnerships to connect public audiences with the university's science and research. "Many people in the world want to know about planets and space, but Stanley's book takes this perennial topic and offers a refreshing look inside the planets, in a way that differs from the deep space-related topics often covered in the news," Burgard says. "From the frozen sea on Jupiter's moon Europa to 1,200-mile-per-hour winds on Neptune and diamond rain on Uranus, the forces and phenomena described in What's Hidden… may seem like the stuff of science fiction," but they're the findings of research labs at Johns Hopkins and around the world—that happen to be ideal for conjuring artistic responses.

In Coriolis, for instance, fiber artist Betty Busby represents a physics concept in an abstract work of silk and cotton. "In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame," writes Busby, a resident of New Mexico, in a description. "I've imagined several clashing storms here."

For Busby and other artists, "partnering with scientists on the cutting edge of their fields is exciting and inspirational," says Martha Sielman, the executive director of SAQA who co-founded and now runs the organization with more than 4,400 global members. "This is anecdotal, but I have a strong sense that many of our members work or previously worked in a science-related field. My theory is that they're drawn to things having to do with fabric because weaving is based on a grid system, and fabric lends itself to geometry. Even if their art later becomes more curvilinear, they're really drawn to that sense of geometry."

Image caption: Claire Passmore created this work of textile art, Hot Stuff, for Fierce Planets.

One of SAQA's artist-scientists, Dolores Miller, lives in San Jose, California. "Dolores is a retired chemist who spent her career doing chemical research for a corporation," Sielman says. "Like many of our members, she started devoting more time to art after she retired." Miller listened to Stanley's talk with enthusiasm before creating Pale Blue Dot 2, one of the pieces in Fierce Planets. In her creation, Earth appears as a tiny dot, dwarfed by the massive rings and many moons of Saturn. "On July 19, 2013, Earth was imaged from the outer solar system (for the third time) by the Cassini spacecraft's camera," Miller says of her piece, referring to the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem, a spacecraft that orbited Saturn for more than a decade before NASA disposed of it in 2017, fearing collision with one of Saturn's moons.

"At this distance, the dynamism of Saturn's rings and moons is evident, while one can barely see the 'pale blue dot' of our home planet," Miller adds.

Artist Claire Passmore picked up on a different aspect of Stanley's research, homing in on parts she relates to in her life on the island nation of Mauritius, off the southeastern coast of Africa. "Living on an island that is geologically new, where the oldest rocks are only 10 million [as opposed to a billion] years old, gives me opportunities to explore the lava fields, caves, and lava tubes that I find fascinating," Passmore says. "Our neighboring island, Reunion, also has an active volcano that offers a spectacular glimpse into what lies beneath Earth's crust, and I get a thrill walking over the still hot (but not too hot) black lava fields."

Passmore's creation Hot Stuff is a large work of fabric art representing volcanic activity and lava tubes in and around Mauritius—and other parts of the solar system, too. "Earth and Jupiter's moons still have active volcanoes, and so may Venus and Mars," Passmore says. "Their volcanic activity acts as a window to the ancient interiors of these celestial bodies."

For Passmore, just as scientists can inspire artists, artists can help scientists break down ideas and reach broader audiences. "Complex data, abstract concepts, microscopic objects, equations, and theories can be difficult to understand," she says. "Yet when combined with visual interpretations or representations, [they] can become much more understandable or 'real' to those who are not experts in a particular field."

Likewise, "conversations between scientists and artists who share common interests can spark new ideas and curiosity in those who may not otherwise … [take] interest," she continues. "These collaborations [provide] an excellent way for us to grow."

Stanley agrees. "Art is critical to the advancement of science; it's arguable that either would perish without the other," she writes in the Fierce Planets exhibition catalog. "No matter how important [the] observations and discoveries [of scientists] may turn out to be, they would mean nothing without the ability to express them to the rest of the world." In that endeavor, Stanley argues, artists play a critical role.

Image caption: Planetary scientist Sabine Stanley gives a presentation at the Exploratorium