The "A" is questionable.

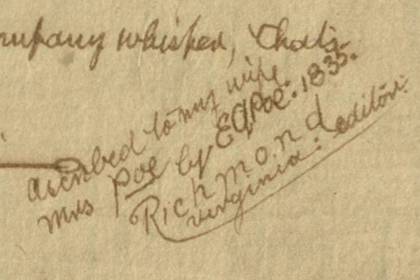

Edgar Allan Poe usually wrote his A's as sharp triangles, but in a manuscript a Johns Hopkins curator recently discovered—a page of sheet music signed by an "E.A. Poe" in 1835—the A is a cursive loop.

Image credit: JHU Sheridan Libraries

If it is found not to be a forgery, it would be the only example of music notes written by the famously macabre writer, and it could support rumors of a secret elopement.

Sam Bessen, curator of sheet music at the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries, was preparing an exhibition a few months ago when he chanced upon the yellowed page. When he shared it with colleagues, one of them "jumped out of her chair," he says.

"It's one of the most excitingly confusing papers I've ever held," Bessen says.

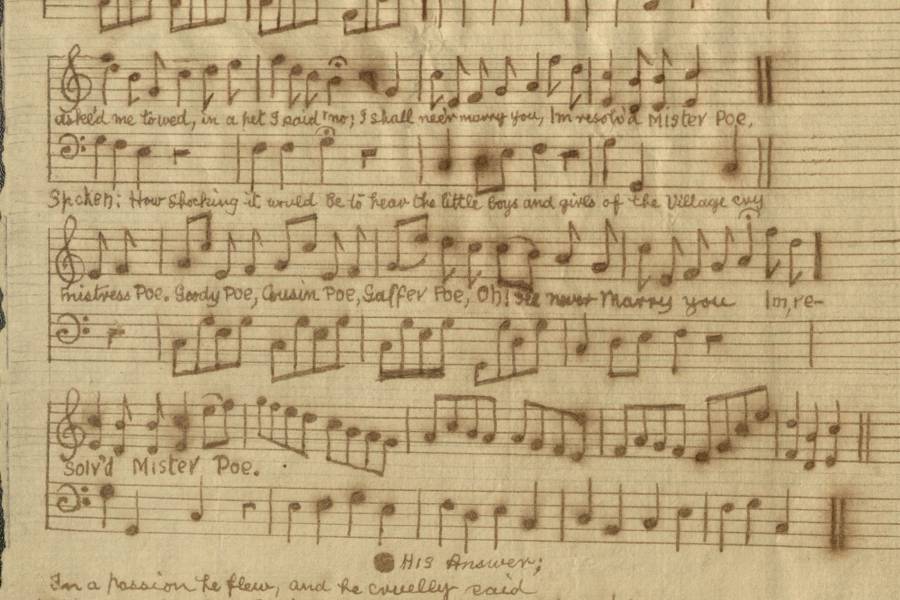

The page features, in ornate handwritten cursive, musical notations and lyrics to Mr. Po, a popular song from the early 1800s. At the bottom right is an inscription, which reads, in part: Ascribed to my wife, Mrs. Poe, by E.A. Poe, 1835 Richmond, Virginia."

The facts more or less line up. Edgar Allan Poe did live in Richmond at that time, when he was named assistant editor of The Southern Literary Messenger at age 26. His writing career was starting to flourish, though his most famous works would come the following decade. In an uneasy part of Poe's biography, 1835 was also the year he became engaged to the object of his devotion: Virginia Eliza Clemm, his 13-year-old first cousin. Though marrying first cousins wasn't necessarily scandalous at the time, the age difference was glaring.

Calling her "Mrs. Poe" in 1835 would have predated their official wedding day, recorded as May 16, 1836, in Richmond. But records show that Poe had obtained a license for marriage to Clemm the year before—on Sept. 22, 1835, in Baltimore, according to Poe expert Richard Kopley, who is currently completing a biography of the writer. "There is disagreement among scholars as to whether they were then secretly married," he says.

If the sheet music was Poe's work, it seems intended to amuse his love. The song Mr. Po is the tale of a woman who rejects her suitor due to his embarrassing last name, shorthand for "Poor." The shallow lady ends up alone, lamenting her decision. (In the document found by Bessen, "Po" is changed to "Poe" with an "e.")

Whoever copied the song was clearly not a professional musician, Bessen says, based on some tell-tale mistakes, such as a giant treble clef before the notations start. For Poe, it would have been "an entirely new medium," he says. "We don't know of any other musical notations in the poet's handwriting."

It's unclear how this paper ended up in the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries, but some Poe scholars have reservations about its authenticity. Kopley says the signature is "not like other examples I've seen … in Poe's letters," pointing to the A as "especially problematic." Jeffrey Savoye, the secretary and treasurer of the Poe Society in Baltimore, also says the handwriting at first impression "does not strongly resemble Poe's."

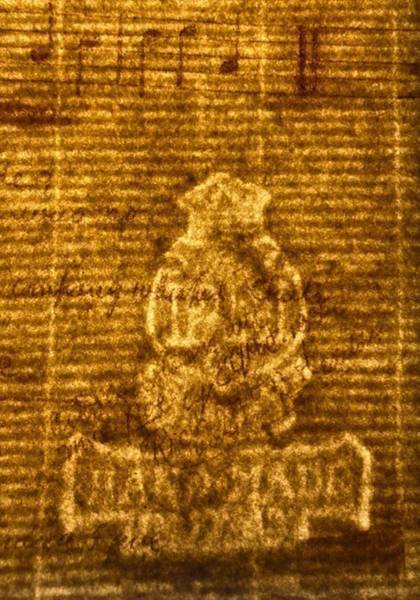

[Conservationists at the Sheridan Libraries](Conservationists at the Sheridan Libraries) are currently investigating the actual paper to see if the 1835 date seems authentic. So far, the ink matches others from the 19th century. A crucial tell could be the watermark on the paper, which the conservationists enhanced in hopes of comparing it to others from the era.

Image caption: Close-up of the watermark

Image credit: JHU Sheridan Libraries

Peter Bower, an internationally respected forensic paper historian and analyst whom Bessen consulted, says he believes "without any hesitation" that the watermark doesn't make sense for 1835. Bower concluded that it was formed via electrotyping— a process not invented until 1838, and not used for producing watermarks until the 1850s, he says.

So if the manuscript is a fake, the nagging question is: Why would someone do this? "What an odd thing to forge," says Scott Peeples, a Poe scholar at the University of Charleston.

"If it's a forgery, it's such a bold forgery," Bessen agrees, wondering why someone would produce something so unusually specific. "We have no other music in Poe's handwriting, and why do an atypical signature?"

Could the forger be George H. Wright, the Californian who originally gave the document to the Poe Society, after quibbling over prices and agreeing to less than he hoped? Bessen is looking into that. Savoye points to another possible suspect: William Fearing Gill, a Poe biographer of the late 1800s "who was pretty clearly a scoundrel and not to be fully trusted," he says.

The E.A. Poe document is featured in Bessen's exhibition, Grace Notes in American History: 200 Years of Songs from the Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection, running virtually and at the George Peabody Library in Baltimore through July. He acknowledges that the mysteries surrounding the strange artifact will most likely endure unless more conclusive evidence turns up. "I don't know that we'll ever be 100% sure, either way."