For Douglas Mao, chair of JHU's English Department, the beautiful friendship started when he was asked to teach a class. Bioarchaeology instructor John Hessler's magnificent obsession flourished after David Bowie walked into the New York City bookshop where he worked. And Patrick Hastings, author of a new guide to the object of their mutual affection, fell hard in a different bookstore—this one in Paris and whose namesake is inextricably linked to its publication.

Image credit: Lauren Simkin Berke

Three scholars, three memorable experiences, three nearly lifelong passions. For most of us, though, the book that unites them, James Joyce's Ulysses, evokes dread, not devotion. Its 700 head-scratching pages of tightly packed alliterative allusions, Liffey life, and Homeric homages make it a tough act to, well, follow.

That's certainly long been my thinking.

When I first came to it a few weeks ago, I was delighted to find (as Joyce might have put it): spunpuns and playword, and later, yes, joysparks and pathosad and ohthehumanity. Yes, whelmedover was I by the streams of interior musings spewing forth. But O! the many lovely phrases and naughty bits, and the indecisive Molly Bloom saying "yes yes yes" 90 times before ending with one final famous Yes!

Just typing those sentences was hard enough—O! Cursed Correctauto—but try reading thousands of them.

This year, the world celebrates the centenary of the book's first publication, and we can't stop talking about it. Joyce wanted his readers to respond that way, and slyly acknowledged that he hoped his magnum opus would "keep the professors busy for centuries." Mission accomplished. As Hastings notes in his new book, The Guide to James Joyce's Ulysses (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022), Leo Knuth, a Dutch Joyce scholar, once published a six-page article dissecting the book's first word, "Stately."

Hastings, chair of the English Department at Baltimore's Gilman School, an all-boys private school located just a few miles from Homewood campus, first encountered the masterpiece—which traces the meanderings of its two main characters around Dublin during a single, long day—as a 21-year-old undergraduate in Paris on a grant researching the history of Shakespeare and Company, a legendary English-language bookstore. He arrived at the start of the store's new literary festival, which included Joyce-related lectures and public readings of Ulysses. "For the rest of the summer, I worked the night shift, slept on a cot beneath the bookshelves, and got a bead on the shop's history," Hastings says. "By the time I got to reading the book itself, I remember thinking, I hope I actually enjoy it. It immediately clicked with me, and I found it a ton of fun.

"I mean, Bloom is an odd guy, but aren't we all?" he adds. "And, yes, Stephen is sad but the way he responds to anxiety and depression is humorous. Characters like the Breens and Bob Doran are funny. Yes, some of these people are a mess. Maybe I'm sadistic, but I find that stuff humorous. Then there are the ironic subversions of what a novel should and can do. [Joyce] knows he's breaking rules; he's having fun himself."

In 1951, New Jersey–born George Whitman opened the bookstore in which Hastings slept and wrote to continue the traditions of an older institution of the same name, located a short walk away. The original Shakespeare and Company, founded by fellow ex-pat Sylvia Beach, operated from 1919 to 1941 as a de facto literary salon for the great writers of the so-called Lost Generation, including Joyce. It was Beach who first printed and released Ulysses in its entirety on Joyce's 40th birthday, Feb. 2, 1922, after it was banned in the United States (see: farting, masturbation, blasphemy, and adult language), following the appearance of some installments in The Little Review, an American literary magazine.

By this point, Joyce had successfully published the short story collection Dubliners (1914) and his first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). These works offered previews of some of the characters (notably, Stephen Dedalus) and techniques (notably, inner monologues) that the author would explore more fully in Ulysses. The new novel was much anticipated, and its reviews were admiring, though unsparing in their criticism. After agreeing with the assertion that "Mr. James Joyce is a man of genius," The Observer's critic expressed concern that its jostling contrasts of "blasphemy and beauty, poetry and piggishness" would turn off readers. The New York Times also damned with generous praise. "It is likely that there is no one writing in English today that could parallel Mr. Joyce's feat," the reviewer wrote, before noting that Joyce was the only individual he had encountered "outside of a madhouse," who had "let flow from his pen random and purposeful thoughts as they are produced." Still, the writer, a prominent New York neurologist, acknowledged learning "more psychology and psychiatry from it than I did in 10 years at the Neurological Institute."

And he ventured a prophecy: "Not ten men or women out of a hundred can read Ulysses through."

One hundred years later, that's still the case. "But with help, once you have a scaffolding and know what's going on, you can start putting together the puzzle," says Mao, an English professor. He remembers first essaying Ulysses without guidance while at Harvard. A few years later as a PhD candidate at Yale, sitting in on an undergrad class as part of a pedagogy seminar, he was required to lead a discussion on one of the book's most mentally taxing sessions, the 150-page episode 15 (Circe), a fantasmagorical brew of real and imaginary happenings during an hour in Dublin's brothel district. By now, he had picked up enough to no longer feel completely lost at sea. "Still," he laughs, "this was literally only the second time I had ever taught! It was a real rite of passage—a way to establish my cred." Now that he teaches the book regularly, he concentrates on "sticking to the text and understanding what is happening in the story," he says. "I think basic comprehension is what first-time readers want."

Hastings says he wrote his book, and created an earlier website—both of which offer episode-by-episode plot summaries of the book, complete with maps that document the wanderings around Dublin of the two main characters—because he wanted to share this work of art that he "found fascinating and challenging and revealing and beautiful, especially given its reputation for density and incomprehensibility." Like Mao, he emphasizes plot when unraveling the book with his high school charges. "I suggest that each of them starts with a single image or even a sentence that they feel they really get," he says. "We slowly build a collective understanding, and all sorts of doors open up."

If there's anything those who have never read the darned thing know, it's the bare bones of the plot. The story takes place on June 16, 1904, which scholars believe is when Joyce and his future wife, Nora Barnacle, went on their first date. We follow along as Dedalus and Leopold Bloom roam Dublin between 8 a.m. and 2:30 the next morning. Near the end of Ulysses, Bloom himself—who has deliberately kept away from his home for as long as possible to avoid interrupting a planned extramarital dalliance of his wife, Molly—revisits the events of his day:

The preparation of breakfast (burnt offering): intestinal congestion and premeditative defecation (holy of holies): the bath (rite of John): the funeral (rite of Samuel): the advertisement of Alexander Keyes (Urim and Thummin): the unsubstantial lunch (rite of Melchizedek): the visit to museum and national library (holy place): the bookhunt along Bedford row, Merchants' Arch, Wellington Quay (Simchath Torah): the music in the Ormond Hotel (Shira Shirim): the altercation with a truculent troglodyte in Bernard Kiernan's premises (holocaust): a blank period of time including a cardrive, a visit to a house of mourning, a leavetaking (wilderness): the eroticism produced by feminine exhibitionism (rite of Onan): the prolonged delivery of Mrs. Mina Purefoy (heave offering): the visit to the disorderly house of Mrs. Bella Cohen, 82 Tyrone street, lower, and subsequent brawl and chance medley in Beaver street (Armageddon): nocturnal perambulation to and from the cabman's shelter, Butt Bridge (atonement).

But really the day's happenings, extraordinary as they might be, are not what the book is "about," Mao points out. "It's about fathers and sons and husbands and wives," he says. "But it's also about the meaning of art, and progress and nostalgia, and Ireland as a nation that's considered marginal, and vicious societal exclusions and antisemitism, and feminism and male bonding."

And don't forget the Homeric parallels. Aside from the author's insistence that the cover of the book be saturated in the exact Aegean blue of the Greek flag, the Irish-born Joyce had no particular affinity for things Greek. Yet he was intrigued by Greek mythology. He even named his alter ego, Stephen Dedalus, after Daedalus, the symbol of wisdom. Frank Budgen, a friend and an early Joyce scholar, reported that in Ulysses/Odysseus, Joyce saw the complete character: a husband, son, and father. "A flawed but decent man," writes Hastings. "The type of hero Joyce wanted for his epic. There was something revolutionary about saying that these two pretty normal people [Leopold Bloom and Dedalus] in a pretty average European city could be the focus of an era's epic," he continues. "The fact that Joyce has promoted to us that normal people can be the main focus of our attention and that we can load up that story with all these other meanings and relevances and allusions and correspondences [to The Odyssey] and literary innovations feels emboldening of the humanist modern era that we continue to live in. We are all focused on ourselves as individuals and at the same time we are aware of how we operate within larger systems. And social media has encouraged us to be the heroes of our own stories."

Still as Hessler, an instructor in the Johns Hopkins Advanced Academic Programs who has taught courses on Ulysses, points out, "If you didn't know it was founded on The Odyssey, you'd never figure it out from reading the book." (Episode headings like Telemachus, Cyclops, and Lotus Eaters were inserted in later editions, based on Joyce's unprinted schema.) "You get what you can out of it, but really I read it for the beauty of its language," Hessler continues. And that's where Bowie comes in, literally. It was the late '80s and Hessler, a few years out of college, was working at a Madison Avenue bookseller while trying to fathom what to do with his life. One day, the iconic rock star entered, seeking a copy of Joyce's Finnegans Wake to bring as a gift for his dinner hosts. "He started talking about his love of Joyce and the musicality of the Sirens episode from Ulysses," Hessler recalls. "He was so eloquent and so persuasive that I took the book home with me and started reading it that night." Since he was studying ancient Greek at the time, the "decipherment aspect was extremely appealing," he adds. "I really like the places in the book where people get lost."

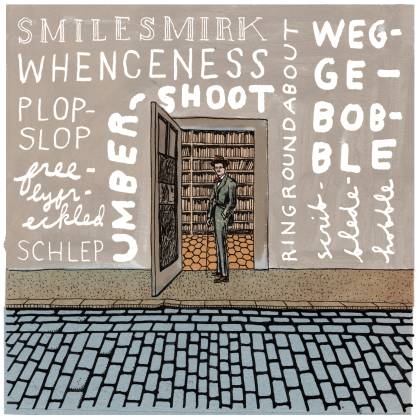

The hallmarks of Joyce's style may be easy to parody, but they didn't flow lightly from his pen. He spent an estimated 1,000 hours writing episode 14 (Oxen of the Sun and then six more months pulling together the following episode (Circe). The labor shows both in the meticulous tracking of the appearances and reappearances of various incidental characters and the consistently inventive language. A bounty of word play ("feetstoops" for footsteps), neologisms ("secondleg" for secondhand breeches), epithets (a "redpanting" dog tongue), and snappy descriptivism ("stickumbrelladustcoat") keeps the reader on her toes. Clever mixed adages ("Marry in May, and repent in December"), sheer lyricism ("the heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit"), keen observations ("fraying edges of his shiny black coatsleeve"), Yoda-like syntax ("about her windraw face hair trailed") round out the pages, along with a go-figure jumble of references, slang, doggerel, and dogma. And, of course, the ever-present stream of consciousness, which careens from thought to thought never giving the reader a chance to parse it. "Joyce showed us what it's like to be inside a person's brain," Hessler observes. "This was a profound breakthrough. Holding this microscope to someone else's brain—the good, the bad, the ugly—it levels human existence, shows our commonality."

As Hastings points out, though, even Joyce conceded that his emphasis on such techniques over story can make for "an extremely tiresome book." But by building up to the stream of consciousness and parodic styles that can so disorient readers, Joyce trains us on how to read the book. "The first few episodes are in what Joyce referred to as the 'initial style,'" Hastings explains. "They blend some inner monologue with mostly dialogue and narrative writing. Then gradually he introduces techniques that shift points of view, or that emphasize musicality and rhythm, or offer parodies of entire genres." Take episode 8 (Lestrygonians), a Hastings favorite. It's rich in Bloom's inner thoughts, but we've gotten accustomed to the style by now and can "better appreciate and be humored by their quirks and curiosity," he says.

More confounding later episodes include scenes, broken up by "headlines," in the newspaper office where Bloom works as an ad rep; a section in which Dedalus and assorted intellectuals jabber(wocky) on and on about Shakespeare; a tour de force of the British literature—via 32 parodies, including of Chaucer, Milton, Pepys, Swift, and Dickens—that has come before Joyce's attempt to reinvent the field and a goes-down-easy parody of a standard Victorian novel that uses bland sentence structures and a preponderance of adverbs and clichés. Think of that last one, episode 16 (Eumaeus), as When Harry Met Sally inserted into a film festival featuring complex love stories like Scenes From a Marriage, L'Avventura, and Woman in the Dunes.

Joyce cited episode 17 (Ithaca)—presented in a question-and-answer format that he termed a catechism—as his favorite, characterizing it as (I am not making this up) "a mathematico-astronomico-physico-mechanico-geometrico-chemico sublimation of Bloom and Stephen." For what it's worth, this reader loved it for its abundance of journalistic detail in describing, say, the action of turning on a faucet or the myriad contents of kitchen shelves and dresser drawers. The episode also fleshes out Dedalus' and Bloom's backgrounds and includes character sketches that pinpoint their differences, right down to the varied trajectories of their urinary arcs.

Also see

Number 18 (Penelope), the final episode, is perhaps its most famous. Presented as an eight sentence, 22,000-word punctuation-free soliloquy from Molly Bloom, it brings Leopold's wife from the shadows as she works out whether to stay with her husband and reviews her other lovers, including the one she has taken to her bed while "Poldy" was killing time for 18 hours.

So, is it all worth it? Like Molly, many say yes yes and yes. "Good things don't come easy," affirms Mao, "and there's definitely satisfaction in getting through. But the real reason to read Ulysses for the first time is that its pleasures are endless. You read it once so that you can return a second and a third time."

Admittedly, I slogged and skimmed when things got tedious, but after reading that last "Yes!" I turned right back to page one. Should you yourself feel ready to tackle this vital part of the literary canon, grab a guidebook, accept that a lot will go over your head, skip a bit. Most of all, remember you have plenty of time, so take it slow.

After all, a lot can happen in one day.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged literature, publishing, english, fiction, james joyce, ulysses