Knicks vs. Wizards, April 8, 2022.

It's the Washington Wizards' last home game of the 2021–22 NBA season. Tonight is fan night at Capital One Arena, so the first 20,000 attendees receive a blue Wizards T-shirt along with a Thomas Bryant bobblehead. The stands are packed with howling fans of all tax brackets, from the feet-on-the-bleached-blonde-wood-floor courtside ticket holders all the way up to the nosebleeds.

Image credit: Monumental Sports & Entertainment

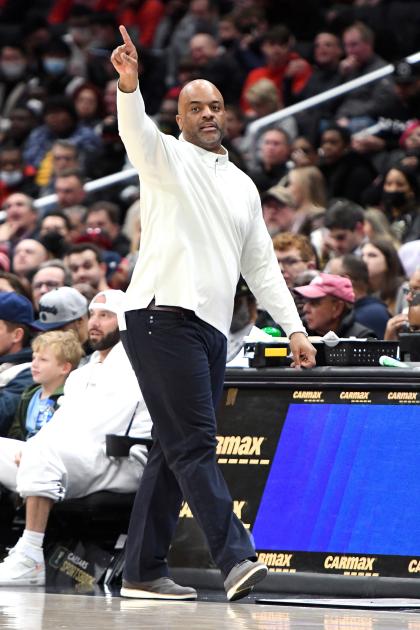

There's a palpable excitement in the air. The ability to physically connect with other hoop fans after years of pandemic separation might be the reason for the universal smiles. After all, both the Wizards and Knicks would miss the playoffs this year, but one wouldn't be able to tell, unless they are close enough to lock eyes with Washington's head coach, Wes Unseld Jr.

The 46-year-old Unseld, A&S '97, stands tall near midcourt when not pacing, with intense eyebrows resting on a fixed poker face. In 48 minutes of regulation time, coach almost never sits. Wearing a quarter-zip Wizards mock turtleneck fleece, he carefully directs his men, often folding his arms as if trying to hide his hands, religiously resolute on maintaining his cool. He's putting the finishing touches on his first year as the team's head coach, with the roaring fans as backdrop and a giant No. 41 jersey hanging overhead from the rafters.

Wes Unseld Jr., who in 2021 was named the 25th coach in the history of the franchise, was born into basketball royalty. He's the son of Baltimore and then Washington Bullets legend Wes Unseld Sr. who wore 41, one of only five jerseys to be retired by the organization.

"I'm a Bullet. I've always been a Bullet, and I always will be," once said Unseld Sr., who died at the age of 74 in 2020. Wes Unseld Sr. is perhaps the most popular Bullet of all time. He played center for 13 seasons at a rock-solid 6-foot-7, traditionally undersized for the position. During his career, the senior Unseld earned Rookie of the Year (1969), was a five-time All Star (1969, 1971–1973, 1975) and league MVP (1969), led his team to four NBA final appearances (1971–79), won a championship (1978) where he was named an NBA Finals MVP, averaged a double-double, and eventually was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame and named one of the NBA's 50 greatest players of all time.

A young Wes got his first training as a coach while his dad was still playing professionally—by helping him stay in NBA shape. According to Unseld's mom, Connie, Unseld Senior struggled with his weight from time to time, which was costly.

"My husband wasn't stingy with his money at all, but he hated paying fines," Connie says. "Back in those days, the team charged $100 for every pound that you were overweight, and my husband loved to eat. So, 20 pounds was a lot of money!"

Unseld Senior had to implement strict diets and workout regimens, which included hitting the local track with a young Wes—who ran alongside him every step of the way, making sure his dad stayed well-conditioned. The whole family would chip in, including Wes' sister, Kim. Wes would run a lap with his dad, and then Kim would do a round, and then Connie.

Young Wes admired his dad and wanted to be around him every chance he got. He had a front-row seat to most of his father's post-playing career accomplishments and eavesdropped on Senior's conversations with fellow NBA legends, but Wes was too young to remember his dad in action on the court.

"He retired when I was about 6 years old. I have fleeting memories of the old room where all the families and kids would hang out, the routine of him as a player, those afternoons after shootarounds and the buildup before the game," Unseld says.

After Unseld Senior retired from playing in 1981, he joined the team's front office, keeping his promise of being a Bullet for life. Wes spent his adolescent years clinging to his dad in and around the arena, meeting players who seemed like giants, running up and down the court, and popping in and out of the locker rooms. Pro basketball life was normal.

"That's what your dad does," he says. "You don't look at it as anything special or unique. Not until you get a little bit older do you realize, OK, this is unusual."

Unseld Senior didn't let young Wes get lost in the privilege of the pro lifestyle. The boy earned his keep. When Wes wasn't doing laps with his dad, he was responsible for keeping his room clean, and he responded by presenting quarters more pristine than a five-star hotel room at check-in time. Wes also excelled in academics in a way that made his father proud. From a young age, Wes understood the role that structure and discipline played in leadership. To be a good leader, one must understand how to be led.

Wes took that assignment seriously.

The Unselds resided in Catonsville, a quaint Baltimore City suburb full of classic single-family homes set on green manicured lawns. Their neighborhood was full of working-class families. Remember—this was the 1970s, before Lakers Showtime and the Jordan era when million dollar contracts and global endorsement deals became the norm. Being an NBA player was still an upper middle-class profession for most.

"We lived in a very close-knit community," Unseld said. "Everyone looked out for one another. As kids, we had the run of the neighborhood. Before cellphones, we spent most of our time outside, riding bikes and trying to find the best pickup games, which were normally over at UMBC or Catonsville High School."

He loved the game and had ambitions of becoming a basketball player just like his dad. However, early on, he knew that height played an important role in turning that dream into a reality. As an adolescent, Wes would measure himself excessively, waiting for that magical growth spurt that transforms young boys into NBA prospects. Kim, who is still taller than Wes to this day, was 5 foot 8 by the time she was in the fourth grade and seemed to inherit her height from their dad's side of the family. Wes clearly took after Connie. He would always joke with his mom saying, "If Daddy had married someone taller, then I wouldn't be so short."

Also see

Connie always believed her son had the potential to do anything. Challenges in academics, social situations, and most sports always came easy to Wes. However, she never saw her son being an NBA player. As glorious as the league was to Unseld Senior, Connie remembers the other side: the wear and tear on the bodies, the effects the media can have on players, and the work needed to not only be successful but to stay in the league. Connie wanted more for her son.

Wes' height finally made its debut around the time he turned 14, when he decided to take his game outside the Catonsville bubble, venturing into different parts of Baltimore in search of competition. The blacktop is everything in Baltimore. Stars like Sam Cassell and Muggsy Bogues earned national attention for what they did in college and the pros, but to earn respect in the streets of Baltimore, performing well on courts like Madison, Boceks, Goldilocks, 101, Patterson Park, and Cloverdale, was mandatory.

"It's strictly AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) and individual workouts now," Unseld says of the current development and scouting process. "All those things are great, but that sense of camaraderie I had with the kids I grew up with, the guys I wanted to go to battle with, some of that's lost."

Unlike most young NBA prospects, Wes never played AAU basketball. However, he did ball for four years—playing center just like his dad—at Loyola Blakefield, a prestigious Catholic high school in Towson, Maryland, that matched up with some of the best schools in Baltimore including Dunbar, Lake Clifton, and Southern.

"We took our share of butt whippings. We stole a few wins too," Unseld said.

Unseld had a successful high school career that ended with him receiving scholarships to many schools. He went on a couple of recruiting trips but realized most of the schools weren't going to prioritize his playing time. Wes knew that college just may be his highest level of play. He had no ambitions of being a professional in another country and had been around enough basketball in his life to know that he wasn't good enough for the NBA. He wasn't bitter, just practical. So, Unseld decided to stay close to home and play basketball for Johns Hopkins.

At Hopkins, Wes could be close to family, get ample playing time, earn a degree from one of the best schools in the country, and study finance. His big plan: enjoy college life, make some memories on the basketball court, graduate, take a year off, and then find work on Wall Street. Wes' dad loved to recite the 7 P's "Positive Preparation Prevents Piss Poor Performance," and Wes Jr. embodied that.

As a young player, Wes was accustomed to coaches pleading with him—"Shoot more!"—but that was never really his style of play. Wes enjoyed letting the game come to him, mastering his role of facilitating. He knew that trying to force the game never worked, and that wasn't only validated while playing at Hopkins, it was enforced.

"Hopkins was great for me, I learned a lot about playing your role. You might not always be the best player," Unseld said. "Well, figure out your niche, work on your craft, and you'll get more responsibility as you go."

Wes learned the power of being coachable and what that meant. Of course, his father's name came up all throughout his basketball career. But Wes Senior stayed in the background.

"Coaches were, at times, concerned about my dad's dynamic," Wes says. "And he never got involved, intentionally, because he just didn't want to overshadow it. He wanted me to be coached."

Wes Senior did not get involved when his son decided to begin his career in the NBA. One would think that having a father who was literally a living legend would deliver instant access to any job in the organization. But that was far from Wes' reality.

"There's always that sense of nepotism. You call it whatever you want to call it," Unseld explains. "There's no one in this business that just walked in on their own. Somebody had to give them an opportunity. Now, just because that door is cracked open doesn't mean it's a given."

Wes began his Wizards career as a hungry and equally curious intern, performing a stretch of odd jobs that he maintained for two full summers.

"Over the years, I served food in the press room, cleaned up piles of trash, washed the players' cars, dealt with piles of dirty laundry, made food runs. Man, they used to make me get up and sing the national anthem at the companywide staff meetings. I truly earned my stripes. Early on I would get frustrated with some of the jobs I was expected to do," Wes says. "As I've gotten older I've come to understand that performing those menial tasks allowed me to learn the business of basketball, from the salary cap to how all the marketing plays into it, the corporate sales, the season tickets, all these things, and you realize there's so many layers that go into making this thing work."

Upon graduating, Wes joined the Wizards with intentions of working in the front office on the personnel side. He worked as a scout, a job with stability and fewer headaches than being a part of the coaching staff but often found himself wanting to do more.

"I think just that itch that you have, that competitive spirit—you don't lose that. Anyone who's played competitive sports, I think you always have a degree of that."

That itch never left, and Wes became fixated on trying to find a way that impacted winning. He went from recruiting personnel to doing more advanced scouting because it tied him to the group and gave him a voice in preparing for an opponent. This work snowballed into a job on the coaching side.

Image credit: Monumental Sports & Entertainment

"I was an advance scout for eight years, on the road quite a bit, looking at other teams, other philosophies, how coaches coach, and how they use certain personnel," Unseld says. "That's probably the first time I started looking at this as a potential career path."

At the end of Wes' last internship, Unseld Senior told his son, "By doing all of these other things, you'll get to where you want to go." And it finally all started making sense. Scouting trained Wes to recognize talent, and all those odd jobs taught him that true team players are willing to do anything in the best interest of the group. It didn't matter if you were scoring 50 points, cleaning the gym, or picking up food, you were a part of the team. Wes had a track record of being a true team player and would never ask anyone to do anything that he hadn't done or was not willing to do.

Wes would go on to spend 15 years with the Wizards, working as a scout with his father who was the team's general manager, before spending his final six years as an assistant coach.

Former NBA center Brendan Haywood was on the Wizards when Unseld joined the coaching staff. Haywood says players gravitated to Wes' easy demeanor.

"The thing I liked about Wes is he's even-keeled. Never got too high, never got too low. Got along with all the players and that was unique at that time because in that locker room, some guys were vibing with the coaching staff and some guys weren't. Wes was the guy that got along with everybody no matter what," Haywood recalled.

Wes also worked on the coaching staff of the Golden State Warriors and the Orlando Magic, and then landed a job with the Denver Nuggets where he stayed for nine seasons, until the Wizards job opened up.

He wasn't the top choice for the Wizards gig, and he knew it. Still, he subjected himself to a rigorous presidential candidate–like vetting process. Wizards personnel combed through the entirety of his career, from his days as an intern to the energy he brought to the Nuggets locker room.

"I've had five or six interviews for head coaching jobs that I eventually didn't get," Wes says. "You tailor it to that team, and you come up with your basic offensive and defensive philosophies and how you do your day-to-day stuff and how you organize. And just like any other interview, you bring all this stuff with you."

Wes had some free time in his schedule while going through the vetting process, so he decided to visit his mom in Maryland. His kids were out of school, so of course they made the trip, excited to see grandma. Wes was also being considered for the head coaching position with the Orlando Magic, a team that was vetting him just as thoroughly as the Wizards were. (The Magic would decide to go with Jamahl Mosley.)

Wes had faith in the Wizards opportunity—and decided to be proactive, by assembling a staff in preparation.

Image credit: Monumental Sports & Entertainment

"You can't wait until you get the job to say, 'OK, let me start interviewing people.' You're calling around and performing your own vetting process as well." As Wes balanced the calls, both of his kids were ripping through the house with Connie. Wes tried not to let the suspense overshadow his family time.

"I remember my kids being so restless one night during the visit," Wes says with a laugh, "I promised them ice cream after I made my last call of the day."

Before they reached the car, the phone number for Tommy Sheppard—the general manager for the Wizards—flashed across Wes' phone screen. Just another step in the vetting process, Wes figured. He jetted down into the laundry room to call Sheppard back and put a load of clothes in before heading out for ice cream.

"Wes," Sheppard said. "Congratulations, you are the new head coach of the Washington Wizards." Wes froze standing over the washing machine just as he did as an intern so many years ago.

"I was so happy for him; it felt so good," Connie says. "Seeing Wes in his first big press conference, with his dad's jerseys hanging over his head, we felt his presence."

There was no shortage of challenges waiting for Wes when the season began—for starters, he was brand new, had to work with guys coming off a shortened summer, was still finishing putting his staff together. On top of everything, he faced a complete roster change.

"I think we all have expectations beginning of the year," he says. "When I took the job, it was a completely different team. That changed literally overnight—the night of the draft. We did a big-time trade and wound up having, I think, seven new players on our roster just like that. You map out a lot leading up to getting the job because you're projecting how you use certain pieces and what would fit best. And then all of a sudden, overnight, it's a different group."

Despite that shake-up, the Wizards got off to a surprisingly good start. Wes' focus and team-ball tactics had set the bar high until injuries and COVID-19 caused him to lose more key players—and a lot of games. Everyone was going through it. And then, once again, the team changed the roster. Now Wes had to game plan for yet another group of guys.

"It's been a balancing act of trying to navigate through this, this being my first year," Wes says. "I get asked: Does this feel normal? I don't even know what normal is. This is normal for me, and this has been a whirlwind, in a good way, because there's no handbook for it." Challenges aside, Wes says he wouldn't rather be on any other team and vows to transform the Wizards into a winning franchise.

"I said this even when I got the job: There's 30 of these in the world. If you think about it, it's an elite club, whether it's here or anywhere, and it's unbelievable to get to this point," Unseld says. "But the fact that it happened here in D.C. where not only my career began but there is the legacy that my father left, that's a very important piece of it. That's not lost on me."