Ask Heidi Herr about Young Love comic issue No. 104, Veil of Love, and you get unbridled performance art. I point to its cover where a despondent but handsome blond gentleman in a groovy yellow leisure suit stands over a seated and tearful nun. "I know you love me—Admit it!" he pleads.

"Oh, this one is just bananas!" Herr says as she reaches for the issue on a table full of comics, their covers adorned with young women in various states of joy, fear, bewilderment, and whatever that feeling is when dancing to Kool and the Gang. She launches into the plotline.

Lee, a Vietnam War vet with PTSD, has had a difficult time readjusting to civilian life in every aspect—romance included. He adopts a "swinging lifestyle," which in his case basically entails a wardrobe refresh and going out to discos until late into the night. Nothing helps. He still has "nightmares of the jungles of Nam." One day, to clear his head, he goes on a bike ride through the country and happens upon a beautiful young woman emerging from a pool. He finds Theresa beguiling, but she barely turns her head to notice him. Undeterred, he tracks her down to the hotel where she's staying, and while following—well, actually stalking—her sees a man assaulting her in the nearby woods. Once Lee senses the danger, he chokeholds the attacker and saves her. Theresa intervenes before Lee kills the man.

Lee assumes that Theresa wasn't in danger but was pretending to be hard to get. Uncomfortably for the modern reader, Lee's jealousy eclipses any concern. "He's like, 'She wouldn't even kiss me yesterday, but now she's romping about with this man?'" says Herr, deepening her voice as she gets inside Lee's inner dialogue. "But things take a soap operatic turn as they always do, and Lee soon learns that Theresa is harboring a wholesome secret."

Theresa will later repay Lee for saving her life, once by fending off the attacker who tries to exact his revenge on Lee with a tree branch to the head, and next when Lee nearly drowns in a lake. Ultimately, Theresa tells him she's glad Lee didn't kill the would-be rapist because she's about to take her sacred vows as a nun.

"So, it's this forbidden Catholic love story," says Herr, a librarian at the university's Sheridan Libraries. "But in the end, she sets him up with a cute waitress, so all ends well. She gets married to God, and he apparently gets over his PTSD through the love of a good waitress [laughs]. This story has everything. I can't get over it—it's so good."

While iconic comic book characters like Batman and Spider-Man and later teams of heroes such as the Avengers and X-Men enthralled readers with their crime-fighting and world-saving ways, from the late 1940s to the mid-1970s an alternate genre thrived: romance comic books. Published by the likes of DC, Marvel, and indies, they featured the adventures of airline stewardess Bonnie Taylor, Mary Robin R.N., Cindy the salesgirl, tragically unhappy actress Lisa St. Clair, and other female characters who seek love and fulfilling relationships. Featuring advice columns, fashion spreads, and allegedly true stories, the books whisked readers away to a more glamorous and mature world for as little as 10 cents.

The first romance comic book, Young Romance, was created in 1947 by writer Joe Simon and artist Jack Kirby—the legendary team that famously gave us Captain America among other superheroes.

Herr and the Sheridan Libraries' Department of Special Collections began acquiring the comics during the summer of 2021. Herr came across the first such book among her husband's collection. "It blew my mind," she says. "I loved the way they dealt with societal trends and social issues of the day."

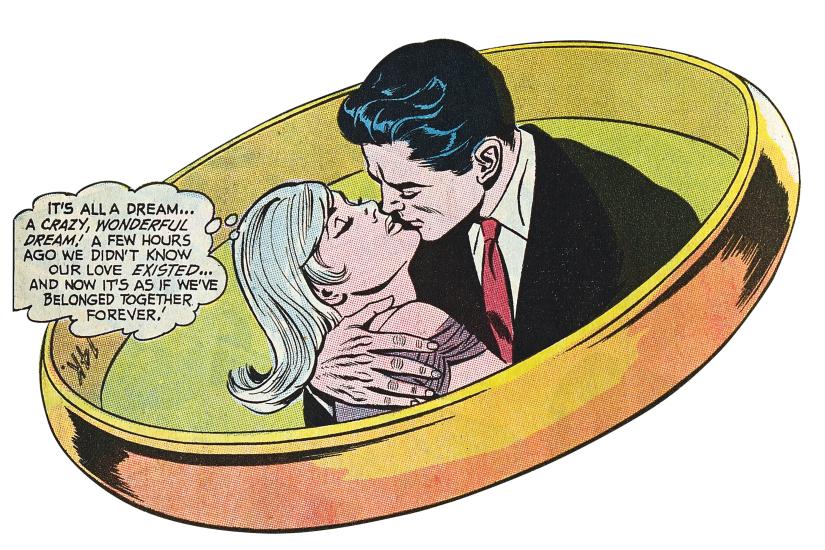

The collection now contains nearly 300 issues and counting, including long runs of titles such as Falling in Love, Girls' Love Stories, Heart Throbs, and Young Romance. As for the plotlines, they mostly revolve around lust, jealousy, marriage, divorce, betrayal, and, of course, teen heartbreak. They're short. They're often messy. They're not high art. And they are rarely subtle. Love blooms, or is stumbled upon, at diners and dance halls and, in the later years, at wild escapades at Woodstock, political protests, discos, and arcades.

Herr says the collection offers an unfiltered look into the past, and it's often not a pleasant picture. In addition to wholesome meet-cutes at a dance or concert, the stories contain undercurrents of racism, domestic violence, male dominance, and date rape. Throughout the late 1940s into the early '60s, women in their pages too often suffer physical abuse at the hands of a man, only to later accept blame for the act, as happens in the Young Romance issue titled "Gang Sweetheart! The shameful confessions of a wayward teen-ager!"

"It's cringy to read some of these stories and look at the panels," Herr says. "It's sadly a recurring theme, especially in the early years of these books, though over time you do see more women stand up for themselves and show a stronger level of independence and self-worth."

The advertisements depict cultural shifts in America over the years. Each decade increasingly values female skinniness, with weight loss ads popping up and weight gain ads fading away. The models in the ads get slimmer and more exposed; dresses give way to bikinis and miniskirts. There are ads for celebrity fan clubs, nail sets, cheap jewelry, and ridiculous knickknacks and toys like Dawk, a mop head with feet.

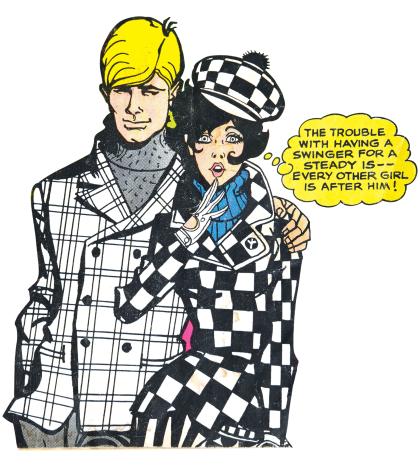

While the stories were mostly written by men in the 1940s and '50s, the publishers did eventually hire female writers, illustrators, and editors, perhaps most notably DC Comics' Barbara Friedlander. She started working in the subscription office in the early 1960s, but was more a lover of soap operas, Hollywood romances, and comics like Archie and Brenda Starr. She eventually became an associate editor at DC working on their romance comic books.

"Once she came on board, the artwork began to get a little bit better," Herr says. "If you look at this issue of Falling in Love here, or even Heart Throbs, the characters begin to look much more with it, much more fashionable, and their costuming and their hairstyles were based on fashion spreads you'd see in Vogue magazine. One column featured a young woman with Reddi-wip beehive hair and amazing Twiggy-inspired fashion straight from Carnaby Street. I love it."

Herr says that Friedlander often cast the women as more nuanced, independent, and in control of their fates, not merely victims of circumstance. She also wanted women to look fun, fabulous, trendy, and aspirational. The comic Secret Hearts features a Friedlander-penned multi-issue storyline called "Reach for Happiness" about a young woman who scandalously ditches her fiancé at the altar to elope with a movie star. The actor would later die in a horrific car crash, leaving the young widow with no choice but to go back to her quaint New England town. There, she encounters her former fiancé and, after some awkward catching up, asks him to marry her.

"We might roll our eyes at this now, but that role reversal was revolutionary for the era. To look back at these stories you must consider the age when they were written," Herr says. "You have to enjoy them for what they are, a look back at our past and changing attitudes on sex, fashion, love, and relationships. Have we grown some? I hope so, but you can also just sit back and buckle up for some wild and groovy rides."

Herr says that the genre didn't so much end abruptly as phase out. She says it's likely that readers' interest gravitated toward the growing cadre of superhero comics replete with female superheroes, and that the dawn of the after-school TV romance specials and Judy Blume books also played a part. By 1974, the romance comics genre was mostly extinct.

Today, these vintage comics are rare, Herr says, because they were not much prized by collectors, and owners typically passed them on to friends after reading. Eventually, they would find their way to boxes in garages or attics or be thrown away altogether. Herr says she has found most of the items in JHU's collection on eBay. Many show signs of heavy handling and wear, such as readers writing the names of a crush in the margins or drawing hearts over male characters they fancied.

Herr and a group of undergraduates curated an exhibit of the collection that was on display in the Brody Learning Commons in spring 2022. The comic book covers can be viewed online at the Sheridan Libraries' exhibits page.

Herr hopes this collection will introduce a new generation of readers to the world of romance comics, and she hopes they cringe, laugh, smile, and go bonkers just as she did.

"I didn't even know this genre existed. I'm sure I'm not alone, and in a way these books have been lost in time."

Posted in Arts+Culture