Eric Paul Roorda, A&S '90, hails from a seafaring family in Holland. His grandfather was a first engineer in the Dutch merchant marine, whose ships were sunk twice during World War I, and his great-grandfather worked on Zuiderzee ferries. Roorda is currently a professor of history at Bellarmine University specializing in the Caribbean Sea, and co-director of the Frank C. Munson Institute of American Maritime Studies at Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut. He is the author of The Dictator Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy and the Trujillo Regime in the Dominican Republic, 1930–1945 (Duke University Press), and editor of Twain at Sea: The Maritime Writings of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (University Press of New England). This essay comes from his most recent book, The Ocean Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke University Press).

Due to global warming, a new Northwest Passage is forming. It is a place that explorers of the past long imagined and sought but which proved illusory—until now.

Martin Frobisher (ca. 1535–94) led three voyages seeking it. James Cook (1728–79) devoted much of his third and final exploration trying to find it, as did George Vancouver (1757–98) in his wake. Sir John Franklin (1786–1847) began his doomed expedition looking for the Northwest Passage in 1845 and was never heard from again. Several more expeditions trying to find out what happened to the Franklin Expedition came to grief over the decades. Finally, in 2014, a Canadian search team located Franklin's HMS Erebus in the Queen Maud Gulf near O'Reilly Island. Two years later, another expedition from Canada found his HMS Terror near King William Island, on the bottom of Terror Bay (which would seem to have been the first place to look).

Also see

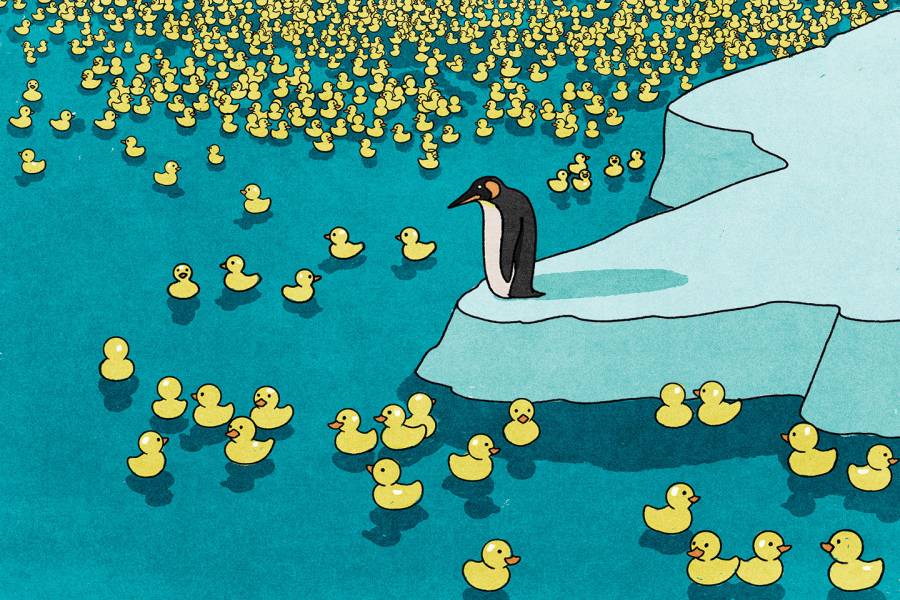

In the meantime, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872–1928), who is best known as the first person to reach the South Pole, led six men through a kind of Northwest Passage in a small fishing boat on a 1903–1906 expedition, but the route he took would never work for commercial traffic. Neither would the routes that the St. Roch of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police charted, while becoming the first and still the only vessel to navigate the Arctic Ocean labyrinth in both directions, during a secret wartime mission from 1941 to 1943. But the new Northwest Passage that is taking shape across the formerly frozen waters of the Arctic Ocean will change shipping patterns, precipitate international conflicts, and alter the maritime environment profoundly and negatively. The harbinger of these changes is a misleadingly innocent symbol: the rubber duck.

A large flock of bath toys, including 7,200 iconic yellow duckies, like the rubber duckies made famous by Ernie of Sesame Street, went overboard from the Greek container ship Ever Laurel in the North Pacific Ocean on January 10, 1992. The ship was going from Hong Kong to Tacoma when it hit a storm in the notoriously tempestuous seas near the International Date Line south of the Aleutian Islands. The winds reached hurricane force, and the waves mounted to 36 feet, slamming the giant vessel so violently that 12 containers broke loose and toppled from the deck. One of the lost containers ruptured somehow as a result, either striking the side of the Ever Laurel or colliding with another container, or both, during its fall. That single 40-foot-long box contained 28,800 plastic (not rubber) bath toys—yellow ducks, red beavers, blue turtles, and green frogs—packaged into 7,200 cardboard and cellophane cartons, each containing one each of the four different animals, labeled with the brand name Friendly Floatees. Freed into the saltwater, the packages gradually dissolved, releasing the enormous flotilla of Friendly Floatees to disperse on the ocean.

After their escape, the rubber duckies, along with their less recognizable multicolored former shipmates, blazed watery trails for oceanographers to study, as they circulated with the North Pacific Gyre and often spun off to reach land or to find more distant seas. In the years since they went overboard, Floatees have washed up on the shores of Hawaii, Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, the west coast of South America, and Australia. Some froze in Arctic ice. A small vanguard traversed the Northwest Passage, caught the North Atlantic Gyre, and arrived in Scotland and Newfoundland, among countless other places.

Many beachcombers collected the charismatic Friendly Floatees that came ashore and reported their finds to a website that oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer established. He realized that the duckie data was a gift to his field, so he brought wide attention to the tale of the fugitive Floatees, to encourage people to look for them and inform him of new discoveries.

"We always knew that this gyre existed. But until the ducks came along, we didn't know how long it took to complete a circuit," Ebbesmeyer said. "It was like knowing that a planet is in the solar system but not being able to say how long it takes to orbit. Well, now we know exactly how long it takes: about three years."

About 2,000 of the toys continue to circle the North Pacific, from Japan to Alaska and back, via the equatorial current. They rarely come ashore now—the last reported find of a Friendly Floatee (a frog) came in August 2013—but it is certain that their story continues to the present day. Many are destined to add more plastic to the trash vortex called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.