In 1610, Galileo peered through his telescope and spotted four bright moons orbiting Jupiter, dispelling the long-held notion that all celestial bodies revolved around the Earth. In 2024, when scientists expect to send the Europa Clipper spacecraft to investigate one of those moons, they too may find evidence that fundamentally alters our understanding of the solar system.

Europa is the sixth nearest moon to Jupiter and is roughly the same size as our own. Thanks to data retrieved by the Galileo space probe—launched in 1989 and named to honor the Italian astronomer—and the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists are almost sure that a salty, liquid ocean is hidden beneath Europa's icy surface, one so large that astronomers believe it could contain two times the water in all of Earth's oceans combined.

Europa itself has been around for 4.5 billion years, but its surface is geologically young, only about 60 million years old, suggesting that it has been continually resurfaced, perhaps through a process much like Earth's shifting plate tectonics. As Europa travels around Jupiter, its elliptical orbit and the planet's strong gravitational pull cause the moon to flex like a rubber ball, producing heat that's capable of maintaining an ocean's liquid state. Hydrothermal energy at the moon's core, left over from its formation, may also heat the ocean at the seafloor.

These unique characteristics have led NASA to deem Europa "the most promising place in our solar system to find present-day environments suitable for some form of life beyond Earth." But in order for life to exist, it needs more than just water and energy. It also needs essential chemicals like hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen. While Europa seems to check the first two boxes, its composition remains a mystery. Confirming all three of these ingredients for life will determine whether Europa is habitable.

"That's the $4 billion question," says Haje Korth, a space physicist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab and deputy project scientist for the Europa Clipper mission. He and his colleagues at NASA and its California-based Jet Propulsion Lab are gearing up to investigate whether Europa might contain the ingredients necessary for life somewhere in its vast ocean.

In late 2024, they will send the orbiter into the skies above Cape Canaveral, where it will begin its five-and-a-half-year journey to Europa. During that time it will fly by both Mars and Earth, using the planets' gravity to slingshot itself 484 million miles toward Jupiter, arriving by 2030. Kate Craft, one of the mission's project staff scientists, warns the long journey will precede even greater challenges.

"The radiation from Jupiter is really harsh," she says. "Our instruments have to be able to survive that."

Roughly the size of a basketball court, the Europa Clipper will carry an impressive suite of 10 separate instruments. Korth says getting all those gadgets to work simultaneously—in the frigid temperatures of outer space, no less—will be another test.

Two cameras, so powerful they will be able to pick up features just a few feet long, will map the moon's surface in color and from multiple angles. Spectrometers will study the chemical makeup of Europa's surface as well as the particles that hover above it. A magnetometer will be able to determine the depth and salinity of Europa's ocean.

Two more instruments, a thermal emission imaging system and an ultraviolet spectrograph, will look for areas where Europa's ocean may have spilled out onto the surface via eruptions or plumes. If scientists find such a location, they would be able to analyze the composition of Europa's ocean without ever touching down on its surface.

Also see

"These would be the most pristine samples of the ocean underneath," Korth says. "This is not a plume-hunting mission, but we'll certainly take that opportunity."

Clipper will spend three and a half years in orbit around Jupiter, performing a flyby of Europa every two to three weeks from as close as 16 miles away, sending back observations that will reach Earth in as little as a week. Between flybys, scientists will pore over this cache of data, adjusting the observations if they see something that sparks their interest—a plume, for example—or necessitates further investigation. Right now, the mission team has planned 45 flybys, but the tour could be extended if funding allows.

While launch is still more than three years away, Craft is already part of multiple studies determining the feasibility and logistics of a Europa Lander mission, the next logical step if Europa Clipper finds the moon to be habitable. A lander could be delivered to Europa from a sky crane—much like the recent Mars Perseverance—and house a cryobot designed to drill through the icy shell and into the ocean below.

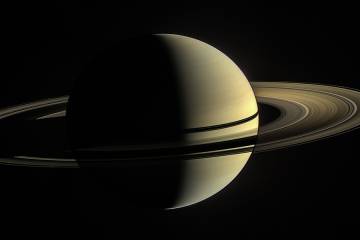

Europa's subsurface waters aren't the only outer-space oceans that APL has its eyes on. In October 2020, the Lab announced it would pitch NASA on the Enceladus Orbilander, a spacecraft designed to orbit and land on Saturn's sixth-largest moon to search for signs of life hidden in its ocean.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged nasa, apl, europa, outer space, the ocean issue, europa clipper