Each May, my family wakes up one morning before sunrise to drive from Baltimore to the Eastern Shore of Maryland where the rockfish run. Charter boat captains ferry novice anglers like us out onto the Chesapeake Bay to fish, then back on shore the crew deftly filets our catch so we can take it home. Last spring was the first time in many years that the trip didn't happen. The outbreak of COVID-19 meant charter boats remained docked, and the restaurants that typically serve rockfish (Atlantic striped bass in some parts) during the season were closed.

For many of us, the pandemic was the first time we confronted mass-scale food system disruptions. We found empty shelves where flour and yeast once were, and, with restaurants shuttered, we were forced to take to our kitchens and make do. "If you see a shortage of something at the grocery store like we did last year, there's going to be a very long chain back to where it was produced," says Dave Love, an associate scientist at the Seafood, Public Health & Food Systems Project at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. At CLF, the scientists and public and environmental health specialists have spent 25 years studying the global food system in order to better understand how it's structured. Through research, education, policy, and advocacy, CLF aims to foster a more resilient and sustainable food ecosystem.

Love, who grew up in coastal Virginia farming oysters, specializes in studying fisheries and aquaculture. When COVID-19 shut the world down, he and a team from Johns Hopkins joined international partners spanning 12 time zones for a weekly call. Fishery scientists, economists, aquaculture researchers, government officials, and public health experts and scientists like Love set about studying the immediate impact of the pandemic on the global seafood industry. Love and his team also looked at country-level data on seafood production, trade, and sales, as well as government reports, news articles, and Twitter posts related to seafood and COVID-19. They learned that a steep decline in charter boat businesses, like the one we hired, was but a sliver of the shift in how fish were caught, sold, and consumed around the world. Their research showed a supply chain vulnerable to mass-scale disruption. Love became the lead author of a report on their findings, published in the journal Global Food Security in March 2021 under the title "Emerging COVID-19 Impacts, Responses, and Lessons for Building Resilience in the Seafood System." The report looks at the effect of the first five months of the pandemic on the industry.

In normal times, seafood likes to travel. By volume, "seafood is the most valuable globally traded commodity," Love says, with global trade topping $153 billion in recent years. "A lot of it is traded from country to country, and we're so interconnected that an issue in one place has ripple effects elsewhere."

The United States, for example, imports 70% of its seafood, primarily from Southeast Asia. That supply was immediately disrupted with the onset of the virus. China went into its first lockdown, stopped exporting, and the largest seafood market in the world disappeared overnight. This also affected places like Kenya, a large consumer of Chinese tilapia. It was a mixed blessing, Love says. "The fisherman in Kenya were happy because they were getting higher prices for their domestic fish, but not everyone could afford it." Meanwhile, local restrictions, such as stay-at-home orders, adversely affected the Kenyan tradition of night fishing in Lake Victoria.

Soon after, flights around the world were canceled and the extent to which major fishing industries depend on domestic air carriers became glaringly evident. "Norwegian farmed Atlantic salmon, for example, is shipped primarily by air freight and they suffered when flights were practically grounded," says Liz Nussbaumer, project director of Seafood, Public Health & Food Systems at CLF and a co-author on the report. "Industrial-level supply chains are designed for economies of scale and profit, and that makes them brittle. If they are only focusing on the bottom line, they are going to continue to have really big disruptions to their supply chains that cascade into so much of the food system."

Maine lobster, which usually ships to Southeast Asia, had nowhere to go and instead went to American grocery stores, where "it was astoundingly cheap for several months," Nussbaumer says. Seafood sales to restaurants evaporated worldwide. Prices plummeted or skyrocketed, creating instability in pricing, while fish processing plant workers and others dependent on the seafood sector suffered financially. Fish, an important source of protein for many underresourced communities around the world, was disappearing from some diets.

For researchers at CLF, COVID-19 offered a unique window into the existing stress points of the seafood industry and an opportunity to understand where the system broke down. "Building resiliency means understanding what has and hasn't worked given this really big shock," Nussbaumer says. "It laid bare how we need to have emergency planning and responses in place in a way that we haven't had previously."

The CLF report memorialized immediate challenges and opportunities, and began to reimagine how the industry might adapt to be nimbler and more resilient. In fact, the United Nations has recommended using the COVID-19 shock "as an opportunity to transform the food system to be more green, inclusive, and resilient," according to the report. "The current seafood system does not work for all people; it falls short in addressing concerns over environmental sustainability, social equity, and nutrition security. Returning to business as usual following this shock would be missing an opportunity to build forward better."

Interestingly, the researchers note, global disruptions didn't inhibit the consumption of seafood at home in the United States as some fisheries rerouted to stores. In fact, there was a 40% increase in seafood sales at grocery stores, versus just a 15% rise in the sale of red meat, according to Love. It had long been presumed, pre-pandemic, that most Americans ate their seafood in restaurants. CLF's research helped show that wasn't the case. One of the most surprising finds of this report—backed up by other research in recent years—is that Americans like to cook fish at home. "It showed us that with restaurants not available, people are more open to shopping for seafood and cooking at home and that's really exciting," Love says, given the health benefits of fish.

Also see

Another interesting outcome of the pandemic may be in the growth of consumer relationships with local seafood suppliers, according to Love. Even before the shutdowns, fisheries in states like Alaska and Maine were attempting to connect consumers directly to their seafood through programs like community supported seafood, or a CSS. In the same way that you might buy a weekly produce box from a farm, a fish CSS allows you to buy directly from the fisherman by paying up front for a designated number of months. Direct-to-consumer home delivery of seafood through meal service companies also expanded during the pandemic, and Love and others suspect this will continue.

My family has certainly become more ambitious in our kitchen. During our year-plus lockdown, we perfected crispy skin on seared salmon, learned the secret to Persian fish stew (fenugreek and dried limes), and attempted rolling our own sushi (that one we'll leave to the experts). My brother figured out how to scale, debone, and filet a rockfish himself at home before we cooked it outside on the grill for a social-distanced meal. We look forward to getting back out onto the open water again, and this time we'll know how to clean the fish ourselves.

From scraps to stock

Image credit: Chloe Niclas

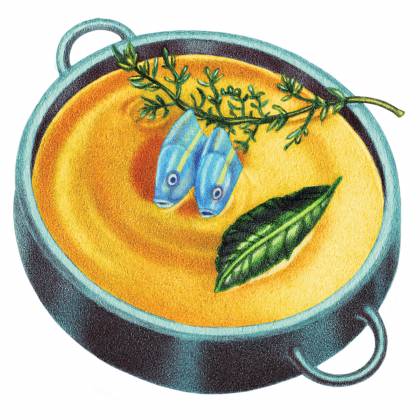

Next time you head to your local fishmonger, consider picking up a fish head, or three. Despite often being tossed as food scraps, the head is the most nutritious part of the fish, rich in vitamins and fatty acids, according to the Center for a Livable Future's Dave Love. Improve your diet while reducing food waste with this CLF-approved recipe for fish head stock, adapted from Bon Appétit. Love recently made the stock for his family, adding a handful of Maine dried kelp for some extra ocean flavor. "My brave 3-year-old seemed to like it, but my 5-year-old thought it smelled too fishy," he reports.

Ingredients

3 fish heads, such as flounder or other whitefish

1 large onion, sliced

1 large leek, sliced

3 peppercorns

3 garlic cloves, smashed

1 bay leaf

A few sprigs of herbs, such as parsley, dill, or thyme

Optional: Handful of dried kelp

Instructions

Rinse fish heads, then add all ingredients to a pot and cover with 1 quart of water. Heat water to an almost boil, but do not let it come to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer for 20-30 minutes. Skim any foam from the surface as it cooks.

Strain stock through a cheesecloth-lined sieve into another pot. Discard solids.

Salt to taste and serve immediately.

—Jeanette Der Bedrosian

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged center for a livable future, covid-19, food systems, seafood, supply chain