Seventeen pages into novelist Alice McDermott's collection of essays on fiction's craft, she writes a deceptively tall order: "I expect the fiction I read to be memorable." Exactly what's memorable varies—it could be "a line or a character or a moment, a turn of phrase or the perfect shape of a chapter, an entire book"—but it is an expectation. It's one of many things that she expects from fiction—to be about lives not her own, to be about the pain and sweetness of life, to be inspired, and more—and this specific verb choice implies the fulfillment of a justifiable or reasonable obligation. These expectations are the duties a novelist asks of herself when tarrying with language on the page. No pressure.

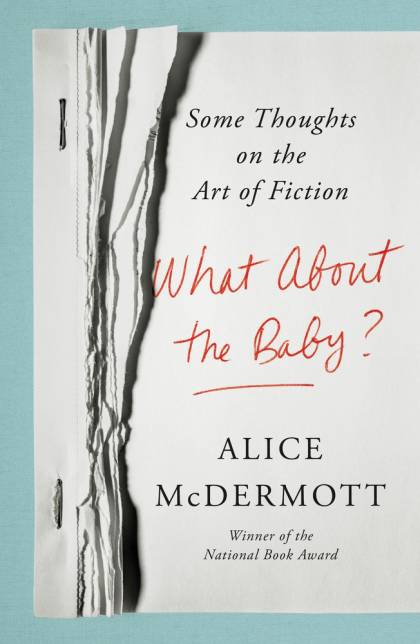

If the idea of a book on craft brings to mind The Elements of Style, New Yorker writer E.B. White's update of his former Cornell University professor's self-published American English rhetoric and usage guide, pull up a chair and dig into McDermott's Baby. Over its 16 compact essays, McDermott explores the mental cul-de-sacs, wrong turns, digressions, and unknown roads an author's mind travels during the writing process. McDermott's wisdom is less of the "how to" than "keep working" variety. The "Sentencing" chapter winds through the waves of insecurity and doubt that come from getting that first sentence right, the entry point that "places the first limitation on the utterly limitless world of the author's imagination." Examples and excerpts abound—Melville's unimprovable "Call me Ishmael"—as well as the admission that there's no reliable formula for getting it right.

McDermott the novelist often strikes me as a veteran jazz musician, fussily unwilling to use too many notes (or words) when the artfully applied few capture the moment, feeling, and character much better. She's equally precise in these essays, dotting her discussions with anecdotes from her personal life and the classroom. The "Sentencing" chapter begins with a compliment from a poet about her sentences, which her insecurity equates with a prison stint, as if her writing incarcerates the imagination. In the way Baby wrestles with a writer's inner life, it recalls Brenda Ueland's indispensable If You Want to Write: A Book About Art, Independence and Spirit, and McDermott's dry wit and bottomless belief in art's capacities make this collection a comforting inspiration: Nothing about this writing thing is easy, and we all get a little lost at times.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged writing seminars, writing, nonfiction, essay