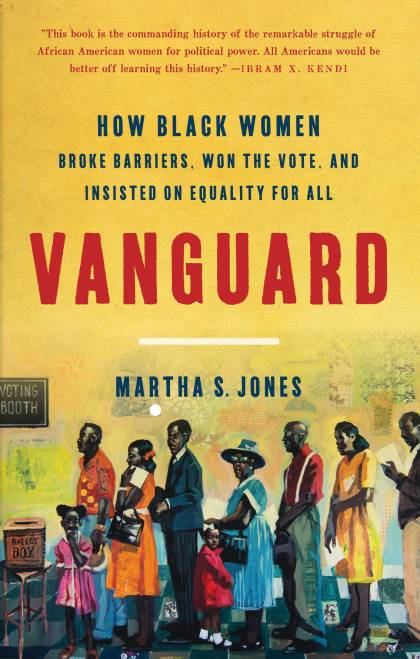

A late-night tweet by Johns Hopkins history Professor Martha S. Jones perfectly captures what makes her recent book, Vanguard (Basic Books), such a bracing feat of scholarship. On November 2, Jones posted a photo of Lyndon B. Johnson posed with a group of people after he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Martin Luther King Jr. and Clarence Mitchell Jr. are framed in the middle. To their left are three Black women. Jones tweeted, "I vote because Patricia Roberts Harris, Zephyr Wright, and Vivian Malone were there when LBJ signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act into law."

Vanguard begins with the observation that the conventional narrative of women's suffrage in America excludes Black women, and Jones addresses that erasure from the 1820s up to Stacey Abrams. Those three Black women in the LBJ photo aren't as instantly recognizable as King and Mitchell, but their efforts and intellectual labor shaped the era. Howard University law Professor Harris seconded LBJ's nomination at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Malone was one of the first two Black students to integrate the University of Alabama in 1963, and she was the first to graduate, in 1965. Wright, the Johnson family cook, had long advised LBJ about the racism she endured. Jones notes that "so much of Black women's political activism had its origins in the educations they earned as domestic workers," and points out a thread of domestic work that runs from the formerly enslaved Sojourner Truth to Rosa Parks. "A kitchen," Jones writes, "was a place to prepare meals and a place from which to plot the future." Showing how Black women educated, organized, and passed on their ideas is what makes Vanguard so vital. In addition to the expected wealth of collateral scholarship and local and state civic archives, Jones turned to small-town and Black newspapers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, annual reports of organizations such as the American Anti-Slavery Society, church records, and other paper ephemera as primary sources. This evidence of Black women's lives is often only found in such archival nooks and crannies, which slyly maps how the historical record of Black women's lives is systemically suppressed. Relearning history is rarely this engrossing.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged book review, nonfiction