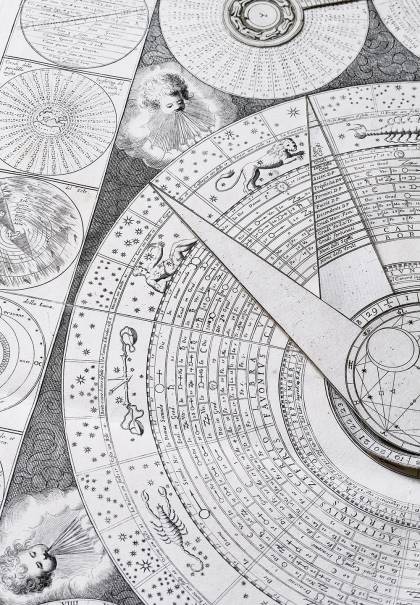

Created in 1690, printed onto two paper sheets from a pair of incised copperplates, and measuring 34 inches high by 25 inches wide, the artifact resembles an intricate, phantasmagorical board game co-devised by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Rube Goldberg. In truth, it is a scientific instrument. Made by the 17th-century Italian Franciscan friar Vincenzo Maria Coronelli, the broadsheet allows its user to make astrological and astronomical observations, calculate Catholic feast days, understand cosmic phenomena such as lunar and solar eclipses, and perform other practical marvels.

Image credit: WILL KIRK / JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

Earle Havens, the curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries, describes the recently acquired artifact as a "paper supercomputer" containing 12 volvelles, or paper wheels, which Coronelli engraved on heavy paper stock and then sewed, knotted, and hammered onto a separate, lightweight sheet. The latter sheet brims with text and accompanying illustrations of the known universe at the time, the 12 signs of the Zodiac, and the Earth's geographic features. By twisting the volvelles, the user could make calculations of the heavens—the exact moment of sunrise and midday, and the days and hours of the new moon—as well as astrological predictions.

A theologian, philosopher, cartographer, author, and mathematician, Coronelli most famously made ornate globes—enormous ones—for wealthy patrons, including members of the nobility. Each of two globes that he fashioned for France's King Louis XIV checks in at more than 12 feet in diameter and weighs about 2 tons. "He always thought big," notes Havens, as also evidenced by the paper supercomputer, "a huge engraving masterpiece that also conveys a vast amount of information."

Arranged for purchase from a New York–based antiquarian bookseller by Havens at the outset of 2020, the item joins a trove of other early modern-period artifacts in what Havens terms the library's ephemeral Renaissance collection. Immediately after securing it, Havens contacted Maria Portuondo, professor and chair in the Department of History of Science and Technology, part of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. Portuondo often brings her classes to examine objects and texts in the library's rare books and manuscripts collection, and she made plans to do that with her Scientific Revolution undergraduate course, though in this particular case, Havens explains, given the artifact's easily damaged movable components, the students would have to handle a library-produced facsimile.

Then came the pandemic, and Portuondo's course went virtual, losing access to the library's in-person resources. But Havens and Portuondo came up with a solution: send copies of the various elements of the device to students in a kit—a backing sheet, a separate sheet of volvelles, and string. Meticulously digitized in high resolution by the library's scanning lab, the kit came with instructions for cutting out the volvelles and sewing them into the backing sheet, then knotting and hammering them.

"It's the kind of project that I probably would not have done any other year," explains Portuondo, "but this year, it's particularly important to get this kind of material in students' hands and build an assignment around it. It's a way of reaching out to them physically, the ultimate user experience."

Portuondo says she wanted her students to go beyond simply describing what each element does, and instead explain its significance.

"Especially during this period of the Scientific Revolution when one way of looking at the world—geocentric, ancient tradition, with the Earth immobile at the center of the universe—changes completely to heliocentric, with the sun at the center and the planets moving in ellipses around it," she says. "It's representative of the period, a document of transition, keeping some things and abandoning others, and I think the big message is 'nothing changes overnight.'"

The class is creating an in-depth analysis and interpretation of the Coronelli artifact for a catalog that will accompany its exhibition at the library when campus activities return to normal. Those who are curious can also eyeball it via the website for the Johns Hopkins Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance, scheduled to launch in the spring semester.

Havens envisions the Coronelli project from a broad perspective, one that jibes neatly with Hopkins' overarching educational philosophy. "We are extremely active in integrating student exposure to primary source materials," he notes, "to the original stuff of history. And to showing students how history, and its reception, is itself a historical event."

While Havens points out that students certainly can benefit from operating the Coronelli device, "even more, they can actually learn what it's like to create something like this," he says. "Everything from the period we're talking about—the early modern period, the first several centuries of printing—was done by hand, and they can develop an appreciation of how documents are created as part of understanding how they work and their place in history."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged astronomy, sheridan libraries, archives, astrology