Helicopter pilot Michael O'Donnell could hover near the ground for only a short time before returning to the sky. On the afternoon of March 24, 1970, O'Donnell had guided his Huey below the dense foliage of Cambodia's mountainous northeast region to retrieve an eight-man reconnaissance patrol that had been inserted to gain information on the size and movements of enemy forces but encountered gunfire early on. Three days into a planned five-day patrol, they needed to be evacuated.

O'Donnell, a 24-year-old from suburban Milwaukee, was part of the helicopter rescue mission involving two unarmed transports and four gunships that were dispatched from an airbase in Vietnam's central highlands. After lingering at 1,500 feet, waiting for the recon team to reach the extraction point, one transport had to return to base to refuel. The transport was on its way back when the recon team radioed that it couldn't hold out much longer. O'Donnell dropped his helicopter into a windy canyon and through a small opening in the canopy, lowered his craft to just above the ground. The recon patrol emerged from the jungle with enemy fire trailing after them. It took about four agonizingly long minutes for all eight men to board, a little longer than the average pop song.

After ascending about 200 feet, O'Donnell radioed to air command, "I've got all eight, I'm coming out," right before his helicopter burst into flames, likely struck by a ground-based rocket. The pilot, his three-man crew, and the recon patrol were officially declared missing in action in 1970. O'Donnell wouldn't be declared dead until February 7, 1978. His remains were discovered in 1995 but not officially identified until February 15, 2001. And on August 16, 2001, he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery, which was created as a final resting place for soldiers on land seized from a plantation owner after the Civil War. O'Donnell left behind his wife, his parents, a sister, his best friend and music partner, and a collection of 19 poems, some of which he included in his letters to friends, discovered in his footlocker after his death.

One of those is a 21-line poem he mailed to his friend Marcus Sullivan on January 1, 1970. Sullivan and O'Donnell met at Whitewater State College in Wisconsin, now called the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater, where they formed a folk music duo. Sullivan served as a combat engineer in Vietnam from 1967 to 1968, and they wrote each other throughout their training and tours. O'Donnell's daily missions transporting the dead and wounded back from the front lines were taking their toll. He wrote:

If you are able

save for them a place

inside of you ...

And save one backward glance when you are leaving

for the places they can

no longer go ...

Be not ashamed to say

you loved them,

though you may

or may not have always ...

Take what they have left

and what they have taught you with their dying

and keep it with your own ... And in that time

when men decide and feel safe to call the war insane,

take one moment to embrace those gentle heroes

you left behind ...

"This poem is such a powerfully modest request to remember, [understanding] that someday everyone's going to know that this war was insane," says Daniel H. Weiss, author of In That Time: Michael O'Donnell and the Tragic End of Vietnam (PublicAffairs, 2019), which looks at the costs of the Vietnam War through the story of one of its soldiers. "And when that time comes, remember us, those who had to go and fight and die for a cause that was insane. There was something about the simple way in which he requests that his comrades be remembered that really touched me."

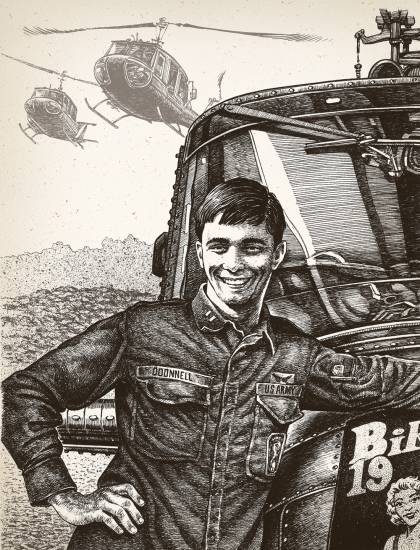

Image credit: John Kachik

The poem so moved Weiss, A&S '82 (MA), '92 (PhD), when he first came across it in Harold Evans' history book The American Century in the late 1990s, he spent the next decade-plus learning more about the young man who wrote it. Weiss, the president and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is a medieval art historian by training, a university and museum leader by career, and a storyteller because his mercurial curiosity drives him. In 1996, when he was the chair of Johns Hopkins' Department of the History of Art, he was in France visiting a museum and came across a famous photo series showing the public executions of three members of the Minsk resistance in Belarus on Oct. 26, 1941. The two men were named, the woman was merely an "unknown girl," and he wanted to know who she was. In the Winter 1997 issue of the Holocaust and Genocide Studies journal, Weiss co-authored a paper identifying the woman as 17-year-old Masha Bruskina, a Belarusian nurse and the first civilian publicly executed in World War II. Her identity was obscured because she was Jewish.

Weiss was struck by a similar need to know more after reading O'Donnell's poem. Although he'd grown up seeing images of Vietnam on the news, he hadn't thought much about it before. He dove into the history, reading journalists' accounts of the war, veterans' memoirs and novels, and works from the larger world of war poetry. He also got in touch with the people who knew O'Donnell—his sister Patsy, his widow Jane, Sullivan, and other Vietnam vets, including Jim Lake, the pilot who flew the other transport helicopter on that mission. They told him stories about O'Donnell the average student, the charismatic musician and songwriter, and the prankster.

Medieval historians don't typically interview sources as part of their research. Those personal connections shaped the writing project. "One of the goals I had in the book was to try to help people understand the difference between a statistic and human tragedy," Weiss says. "Michael O'Donnell was a statistic on March 24, 1970, but he was a human tragedy for Jane and Marcus and Patsy for years."

The tensions that separate a micro human tragedy from the macro world of war make In That Time a reminder that we're still living with Vietnam, even if we don't think about it that often. Weiss tells the story of Michael O'Donnell, by all accounts a fairly ordinary young man whose life ended in an extraordinary act of courage, but there are thousands of such stories that could be told about the Vietnam War. Weiss folds O'Donnell's story into a compact discussion of how the U.S. got involved in Vietnam in the first place, from the waning days of French colonialism to the deployment of troops under Lyndon B. Johnson and on through Richard M. Nixon's Vietnamization policy to train and equip South Vietnam forces while reducing American forces.

In trying to situate one pilot's experiences inside the larger geopolitical decisions and forces that cause countries to enter and remain in wars, Weiss arrived at a clear moral quandary. "As I read all of this material, and I tried to relate it to the experiences of one man in Vietnam, it became clear to me that in the midst of all that noise, of all those details, there was a rather straightforward moral story about leadership," Weiss says. "What is leadership's responsibility in times of war?"

Weiss compares the wartime thinking of Johnson's and Nixon's administrations to Abraham Lincoln's during the Civil War, when he suggests America began its institutional tradition of remembering fallen soldiers. In That Time opens at O'Donnell's burial and segues into discussing Arlington National Cemetery's origins. The Lincoln administration recognized the need for reconciliation whenever war ended, and wanted to start by honoring the men who fought. Weiss quotes James Russling, a Union soldier who wrote an essay for Harper's Monthly commending the government for "tenderly collecting, and nobly caring for, the remains of those who in our greatest war have fought and died to rescue and perpetuate the liberties of us all."

Lincoln, in Weiss' mind, knew he was sending people to their deaths and carried that weight every day of his life, as evidenced in his speeches and personal letters. Johnson and Nixon, in Weiss' reading, tried to use military interventions to achieve the political goal of containing communism. "Leadership matters," Weiss says. "And under what circumstances is it appropriate to send other people to die in service of an idea that you're developing?"

Have we forgotten the Vietnam War? Think about it: In 2020 we're as far away from the Vietnam era as we were from World War II in 1998 when Tom Brokaw's book The Greatest Generation, Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan, and Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line ignited a cottage industry of nostalgic reckoning about that time period. Sure, Ken Burns gave the Vietnam War his stately treatment on PBS in 2017, but the epic, 17-plus hours long, didn't catalyze much renewed examination of the era beyond reviews.

Literature by Vietnam veterans, be it novels or poetry, doesn't seem to occupy the same exalted space as Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead, James Jones' World War II trilogy, Wilfred Owen's World War I poetry, or even Iraq war veteran Kevin Powers' The Yellow Birds. The world of Vietnam War literature written by vets typically goes Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried, Ron Kovic's Born on the Fourth of July, Philip Caputo's A Rumor of War, and maybe Harold Moore's We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young. Movies about the war occupy a larger part of the popular imagination than soldiers' own accounts.

Tobey Herzog has observed this sidelining of veterans' stories at various times over the course of his career. A professor emeritus of English at Wabash College in Indiana, Herzog is a Vietnam veteran who began teaching courses about that war's literature in the late 1970s. "After my time in Vietnam, I came back to graduate school and tried to forget that part of my life and move on," he says, adding that when classmates found out he had been in the war, they encouraged him to teach a class about it. In 1992, Herzog published Vietnam War Stories: Innocence Lost, an overview of Vietnam novels and nonfiction, including Caputo and O'Brien, that wrestled with and contrasted what they say about war with the genre conventions found in popular fictions. He notes that when he was writing the book in the late 1980s there was a fascination with the war given the profusion of entertainments that use it as a backdrop, particularly the idea of the Vietnam veteran as psychologically complicated outsider. He ends the book hoping that American audiences were on their way to separating popular fictions from what soldiers have to say for themselves, imagining a time when the country has "almost completed its own rite of passage as it contends with the lessons and aftermath of the Vietnam War."

Asked if he still thinks America has contended with the lessons of Vietnam 30 years on, Herzog is less reassuring. "No, to be quite honest, we still have not learned the political and military lessons of Vietnam," he says. He adds that, beginning in the 1980s after the installation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, "we have a better understanding of how to separate the soldier from the politics of war. That's the biggest lesson that we've learned."

Image credit: Public Affairs Books

Weiss' In That Time folds the soldier back into politics to show war's ripple effects on one family over decades, an approach that involved talking to veterans. "I wanted to do justice to their stories and produce a book that was credible, so I listened to them when I was writing," Weiss says. "They told me what the war was like. My goal was to try to tell the story of that day in a way that brings people really close to what trauma looks like."

Those traumas happen many times over. Lake was the pilot who first deployed the recon team O'Donnell swooped in to rescue. Though only 19 at the time, he'd been in Vietnam for 11 months and had more flight experience than O'Donnell, making him the mission command. After O'Donnell's craft exploded, he watched a gunship fly over the crash site looking for the downed vehicle with rockets and tracers chasing after it from the jungle floor. He took his own helicopter into the valley as best he could, hoping to see anything, before giving the order for everybody to return to base. "I made the hardest decision of my life," Lake tells Weiss. "No one ever went back. The war went on, the next day, more war. We carried on."

From Patsy, Weiss learns that O'Donnell's family initially received two official telegrams from the Army following her brother's crash—one informing them he'd been declared MIA, another about a week later saying that efforts to reach the crash site were unsuccessful. They received several of these MIA updates a year until the family requested that Michael's status be changed to Killed in Action in 1978. Michael's father died in 1987, his mother in 2003, but Alzheimer's robbed her of knowing her son's fate.

The Department of Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, created in 2015, keeps track of Americans still unaccounted for in Southeast Asia as a result of the Vietnam War and the remains repatriated since 1973. By its last report, issued July 2019, 1,587 Americans are still unaccounted for in Southeast Asia and the remains of 1,059 Americans have been repatriated. O'Donnell is but one of those former MIAs, and when Sullivan first heard that his friend's remains had been found, "I was devastated at the thought that he and the others had been there at the crash site in the jungle, in Cambodia, for all those years," he tells Weiss.

Sullivan, whom Weiss now calls a friend, shared samples of the songs he and O'Donnell wrote in college. "Michael was a songwriter, a good one, so he was very comfortable with the mode of writing about what he was feeling and expressing that in ways that were artful," Weiss says. "I think poetry came to him quite naturally as an outlet for those feelings in the same way it did for Wilfred Owen in the First World War, where there was a something about being able to turn terrible experiences into something beautiful. I think [O'Donnell] had a drive to produce something of enduring beauty in the midst of horror."

O'Donnell started writing poems shortly after he arrived in Vietnam in October 1969. One, dated "25 Oct 1969", reads:

each of us

is a can of tomato paste

and though we may all

not have the same label

as we spin through the air when we land too hard

or get torn,

from the outside or within

we spill out

and stain the hand of everyone who knew us ...

He imagined he might collect his poems into a book titled Letters From Pleiku after the war. Instead they were circulated among soldiers after his death, eventually making their way to civilians' eyes. Weiss first came across O'Donnell's poetry in Evans' book and then again in Andrew Carroll's War Letters: Extraordinary Correspondence From American Wars. O'Donnell's most well-known poem, which gives Weiss' book its name, is inscribed on the north side of the Memorial Wall at the New York City Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza in Battery Park.

"I remember reading the poem and looking at this picture of this nice-looking young man and thinking about what a sad, powerful story it was," Weiss says of first reading that poem, pointing out that O'Donnell was still MIA at the time. "He spoke of this very powerful need to be remembered for those who are left behind, and just after he wrote it, he himself was left behind."

In the years since O'Donnell's crash and the inglorious end of the Vietnam War, at certain times, in certain places, people do remember those gentle heroes left behind. As for feeling safe to call the Vietnam War insane, maybe we are not there yet. "If you were to [ask] any American citizen who had been paying attention to the war in 1975, I think to a person they would have said, Well, whatever else we learned from this war, we absolutely learned not to commit our country to pursue a bad political idea without careful review and respect for the loss of human life," Weiss says. "And yet we have done that on numerous occasions since."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society, Alumni

Tagged literature, american history, vietnam war