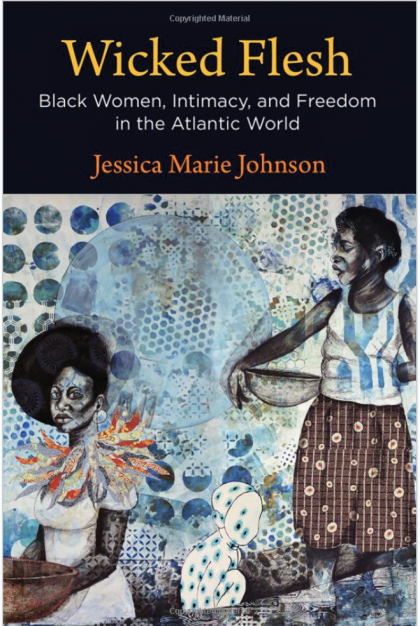

About halfway through Jessica Marie Johnson's new book Wicked Flesh (University of Pennsylvania Press), the Johns Hopkins assistant professor of history shows how easily Black women can be erased from history through bureaucracy. In the book, Johnson explores how free Black women in Africa and America used their social relations and kinship to acquire, wield, and retain power in the 18th century. She notes that French officials were obsessed with census taking in colonies, which included enslaved populations along the Gulf Coast. Free Black women, however, don't appear in these documents. "For colonial elites," she writes, "if black women could not be used or possessed as laboring, sordid, or lecherous subjects, they received little or no mention—but black women did not disappear."

Finding ways to see those women involved Johnson wrangling a small library's worth of collateral scholarship and primary sources from the archives in multiple countries and languages. That can make Wicked Flesh a slow go at first. But keep going: Wicked Flesh is a work of bold, creative history, propelled by a scholar as gifted a writer as she is a researcher. Johnson gives central focus to both Black women and 18th-century New Orleans in her study, examining how free Black women interpreted slave codes, sought manumission acts, and supported each other when their freedom was contested by officials.

Johnson pieces evidence of these women's lives together to tell their stories, such as Charlotte, a biracial 17-year-old who was arrested as a runaway in 1751. Charlotte, the daughter of an enslaved woman and the Frenchman who owned her, had sought an audience with the wife of the colonial governor to obtain her freedom. Charlotte, as Johnson writes, "learned to navigate a precarious and changeable terrain of status, gender, and race," and she knew that seeking freedom from her father/owner, a man of distinction in the eyes of officials, was probably futile. Instead, Charlotte approached the most powerful woman in the colony: "For Charlotte, her freedom was a project that only another self-identified woman could understand." Such subtle efforts to understand 18th-century colonial life from Black women's perspectives gives Wicked Flesh its potent punch. A vital addition to relearning America's history of slavery.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged history, american history