Carolyn Sufrin was a first-year OB/GYN resident at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in 2004 when her interests in providing care and advocating for change converged. As an undergraduate, she learned how Western medical science had been complicit in promoting gender stereotypes, shaping a health care system that treated men and women differently. Sufrin chose obstetrics and gynecology because she wanted to be involved with women's and reproductive health as both a clinician and advocate. Even with that awareness, though, there was a population of women she hadn't thought about prior to getting called for a delivery as a resident. Her patient was an inmate from a nearby jail, and she was shackled to the bed.

"It was jarring, very troubling and confusing, I had no idea what I was supposed to do, if anything—and I wasn't the woman in shackles," recalls Sufrin, Med '03 (MD). She sits in her compact office at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, where she's the associate director of the fellowship in Family Planning, thinking back to that moment. Entering that delivery room sent questions running through her head. Does being here make me complicit in this mistreatment?

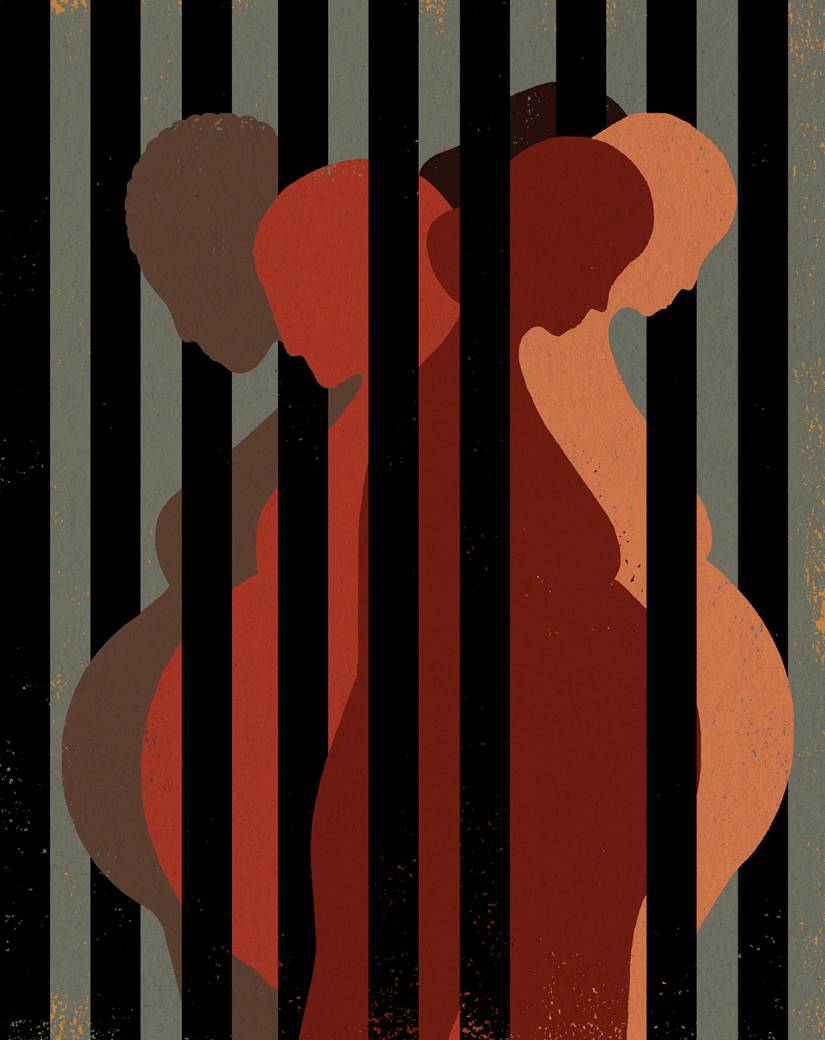

Image credit: Hanna Barczyk

"It made me realize I never thought about the fact that there were women who were incarcerated, let alone pregnant women who were incarcerated," says Sufrin, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at the School of Medicine. Nonmaleficence is a core concept of doctors' ethical training: First, do no harm. At that moment, Sufrin also thought about French philosopher Michel Foucault, whose hybrid works such as Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality trace social power structures' roots in prison systems and how those institutions aim to control people's sexual and reproductive bodies. "Both of those ideas were in the room with me."

Over the next decade she combined her medical education and clinical practice with an exploration of women's health care in prisons. Her resident research project investigated access to contraception and abortion services for incarcerated women. A family planning fellowship took her to the University of California, San Francisco, where she started meeting with the medical director of the San Francisco County Jail. Sufrin worked as a care provider at the jail once a week, starting a clinic that addressed issues that were sometimes outside the purview of the jail's nurse practitioner, but not pressing enough for a transport to a hospital. "Here I was trying to be compassionate and provide just and thoughtful care in a space of punishment," she says. "For many of the women I met, it was the only place they got health care. What's going on here—especially in a city like San Francisco with a robust safety net?"

She turned to anthropology to answer that question. While earning a PhD, she followed women who were pregnant or had given birth while incarcerated at the San Francisco jail. Jailcare (University of California Press), her 2017 book that grew out of her dissertation, provides an intimate look at the contradictions of providing care in a place of punishment. These women were often navigating the violence of poverty, substance abuse disorder, and racial oppression in their daily lives, and jail was the only place they received health care coverage.

This snapshot view of one jail only scratched the problem's surface. Sufrin's San Francisco research provided a window into how health care varied across the state's and country's prisons and jails. In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that failure to provide prisoners with medical care was cruel and unusual punishment—which, as Sufrin notes in Jailcare, made prisoners the only people in the U.S. with a constitutional right to health care. Prisons and jails have to provide health care to people imprisoned, but there's little oversight or mandatory standards governing how that care is provided.

Also see

More troubling, what little previously published scholarship existed about reproductive health care in women's prisons and jails helped Sufrin recognize how little is known about the current situation. The data she came across—that 6% to 10% of incarcerated women are pregnant at any given time, resulting in an estimated 1,400 births per year—came from late '90s federal reports that didn't indicate how those estimates were obtained. And when looking into what data the Bureau of Justice requires prisons to collect, she realized "there is a mechanism for collecting information about deaths in custody, but there's nothing about births in custody," she says. "There's no recognition that that's kind of an unusual event."

In March, Sufrin and her research team published the first results of her Pregnancy in Prison Statistics (PIPS) study, which she launched in 2016. The study compiled and analyzed reports from 22 state prisons and the Federal Bureau of Prisons over a 12-month span between 2016 and 2017, and it is considered the first comprehensive assessment of women who are pregnant or give birth while incarcerated. Over the 12-month period, 1,396 pregnant women were admitted to prisons. Of the 816 pregnancies that ended in prison, 92% resulted in a live birth, 6% were pre-term, and 30% were cesarean deliveries. There was tremendous variability in outcomes from state to state.

"What PIPS has done, at a national level, is given us a sense of how many women give birth in custody each year," says Rebecca Shlafer, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School who focuses on families affected by the justice system. Shlafer works with the Minnesota Prison Doula Project, a community-based organization that supports pregnant women at the Minnesota Correctional Facility–Shakopee, the state's only women's prison.

Shlafer adds that during fundraising for the doula project, potential donors often ask a basic question: How many pregnant women are there? "Nobody knows," Shlafer says. "There is nothing like asking a funder for money and they ask you, 'How many people are you going to serve a year?' And we have no idea because [the prisons] don't systematically collect that information."

The exasperation in Shlafer's voice speaks to the frustration that runs beneath the surface for a growing number of doctors, public health researchers, and nurses studying the intersection of women's reproductive health and incarceration. Some other question may have brought them to the subject—the experience of pregnancy during incarceration, what happens to the kids born to women who are incarcerated, how a woman's incarceration impacts family health outcomes—but the first investigative steps reveal that so little attention or oversight has ever been paid to women in prisons and jails that there's paltry baseline information.

A quick note before we go any further: This story is going to be frustrating. It's not going to be frustrating just because it mentions women being shackled while giving birth, which comes up because stories about that practice are often the few times that reproductive health of incarcerated women becomes mainstream news. It's going to be frustrating because it's impossible to talk about women's reproductive health while incarcerated in a general way because it varies so dramatically. The National Commission on Correctional Health Care, on whose board Sufrin now sits, is the professional accreditation organization for health care facilities in jails and prisons, but it's voluntary. Federal prisons have one set of guidelines, states have another, and local jurisdictions have oversight over local jails. There is no mandatory set of standards or mandatory system of oversight for state and local institutions. As Sufrin tells me, when she's asked what it is like for incarcerated women to access prenatal care—or what it is like for incarcerated women to access contraception, or healthy diets—the accurate answer is also the most frustrating one: It depends. It depends on what kind of prison/jail it is, which state it is located in, how well the women's facility is staffed, what kinds of health care resources it has access to, and more.

Researchers simply don't have enough information yet to describe what the present situation is, an absence that complicates suggesting policy reforms or standards of care. It's almost as if America's decentralized carceral and health care systems can't see the women they ostensibly oversee. First, they're imprisoned, which removes them from society at large. The same policy forces driving mass incarceration in the U.S., which disproportionately affects lower-income individuals and people of color, affect the women's prison population with a few caveats (women in jails are more likely to be arrested for nonviolent offenses and are in custody pretrial). But when we think about mass incarceration, what comes to mind is a man because of the size of that population. According to the nonprofit think tank Prison Policy Initiative, 2.3 million people are confined nationwide as of 2019, with women making up less than 10% of that population. Between 1977 and 2004, the population of women incarcerated increased 757%. And while overall incarceration rates have decreased since 2009, for women they're either growing or decreasing at a much smaller rate than for the male population.

This is the part of the story where some official, contextualizing data from the U.S. government should go, but there's no single source that provides a discrete picture. The Prison Policy Initiative does a fair job of collating what information is available from federal and state reports. According to its Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019 report published in March: "The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 109 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories."

The PPI's corresponding report for women from October estimates there are 231,000 women and girls incarcerated in the United States. Determining that number required developing a ratio based on available data. Nearly half of those women are held in jails instead of prisons, and gender information from jails can be incomplete or missing.

In her office, Sufrin discusses these data gaps patiently, as if explaining them to a child, as well as the efforts of her team and of other researchers to address them. Behind her is a row of boxes containing mailers of surveys to nearly 1,500 jail administrators in the United States, part of her ongoing research into counting the number of women who give birth or are pregnant while incarcerated and assessing the quality of care they receive. Written on a dry-erase white board opposite her desk is a list of projects in process, tracking progress from data collection to publication. "It's just utterly baffling to me and to other people doing this work that [jails] have no idea how many pregnant women there are," she says.

In June 1994, the Illinois Pro-Choice Alliance and the Ms. Foundation for Women co-sponsored a conference in Chicago. Twelve attendees, all black women involved in some aspect of reproductive health and rights movements, met in a hotel room to draft a response to the Health Security Act of 1993 prepared by then President Bill Clinton's administration. Those women argued that the proposed health care reforms didn't do enough to address the concerns of women of color, who were already facing health care disparities, and wrote a response that centered on black women. Such a plan would need to be affordable. It needed to focus on wellness and prevention. It needed to address issues that disproportionately impact women of color: cervical and breast cancer, infant and maternal morbidity and mortality, intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS. To get elected officials to notice, they placed a full-page ad titled "Black Women on Health Care Reform" in The Washington Post and the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call. They called their approach "reproductive justice," and it has become one of the driving ideas in contemporary politics to understand how race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality inform that intersection where reproductive health and social justice meet.

Chances are if you've heard about the shackling of incarcerated women during pregnancy over the past 25 years, it's owing to the advocacy efforts and grassroots coalition building that came out of that 1994 meeting. The Atlanta-based SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, formed in 1997 by women and organizations that grew out of that conference, has consistently promoted policy changes to the states that still allow the use of restraints. The First Step Act of 2018 prohibits the use of restraints on pregnant women in Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities—unless they are a threat to themselves or others or a flight risk—and in October, the Georgia Dignity Act went into effect, banning the practice of shackling pregnant and postpartum women, as well as guaranteeing access to items such as sanitary napkins. Currently, 29 states and Washington, D.C., have laws prohibiting shackling in labor.

Banning the practice is but one step toward providing better care for pregnant women who are incarcerated, and reproductive justice continues to inform Sufrin's thinking. Her Johns Hopkins research group is called the Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People. "My research has always been inspired by a sense of wanting to advance social justice and reproductive justice, and I continue to learn about that framework from women of color who are the leaders, who created that term and agenda," she says. "I believe strongly in the power of that research to make a change. One thing that I'm always thinking about is how I can do better as a researcher. I am trying to recognize that in formulating research questions in the past I haven't always involved directly impacted people. And that is something that I am working to improve."

Reproductive justice needs to center women of color because medical and social sciences, historically and currently, insufficiently recognize how race, gender, class, etc., impact their research and understanding. Shlafer at the University of Minnesota points out that "if I had a question about policing I would go to my criminology colleagues here and they're the experts on policing," she says. "But when you're talking about maternal and child health in the context of incarceration, who is the expert? I think part of the reason we have such a gnarly problem right now is that no singular discipline has claimed it."

Lorie Goshin, an associate professor in the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing, tells me that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses—the professional organizations of health care providers who see women who are pregnant and incarcerated—have both outlined standards of care. Goshin, a former correctional nurse herself, collaborated with Sufrin on a survey of around 900 nurses nationwide who work in the perinatal hospital units where women who are incarcerated are taken for deliveries. She asked them a variety of questions, including: whether they've cared for incarcerated women, were the patients shackled, and does your state have a shackling law, among others.

The surveyed nurses had considerable experience caring for incarcerated pregnant women, and most reported that women were sometimes shackled during labor. "Very few, only 17%, knew that their own professional organization had a specific position statement on this group of women," Goshin says. "Even less, around 7%, correctly knew whether their state had a shackling law."

Goshin is currently working with community programs that address the root causes of women's incarceration, such as homelessness, poverty, substance use, and serious mental illness—a career shift into evidence-informed advocacy common to researchers in this emerging field. Shlafer says her work with the Prison Doula Project initially didn't focus on shackling. That changed when their doulas witnessed horrifying treatment of women restrained before and after childbirth. "We decided we need to pivot and think about the ways in which we can use this evidence to improve the lives of the women and girls who are pregnant in custody," she says.

That's one reason why Sufrin's PIPS study has been so groundbreaking: It's providing a starting point for eventual policy discussions in the absence of any understanding of the situation at all. Jennifer Bronson, a former statistician at the Bureau of Justice Statistics, says the scale, scope, and detail the PIPS study documented has never been done before. The Department of Justice conducts surveys of people in jail and prison, through which some health information is collected. The Department of Health and Human Services keeps track of births. But women who are both incarcerated and giving birth? "To my knowledge, it isn't something that government agencies are routinely doing right now," Bronson says. "DOJ and the Bureau of Prisons collect a few data points. I don't think Health and Human Services currently collects any birth or pregnancy data on incarcerated populations. That's often what happens—the health agencies don't capture people who are incarcerated and the justice agencies don't collect the health data. So there ends up being this gap where agencies are asking, "Who can collect these data?"

Sufrin's March PIPS report is only the first analysis from her team. The team also collected information on policies and services for incarcerated pregnant women and other pregnancy and postpartum outcomes, which they plan to publish: information on breastfeeding, abortion, postpartum depression, the controversial practice of tubal sterilizations, and pregnancy data from the country's five largest jails. A subsequent study involved interviews with women who were pregnant while incarcerated in Maryland and in Ohio to begin to provide some understanding of how being incarcerated affects their pregnancy decision making. And a big project they're exploring is the management of opioid use disorder among pregnant women in jails, surveying 3,000 jail administrators and interviewing pregnant women in jail to understand their perspectives.

All of which will, eventually, provide some starting points for researchers to begin working on policy advocacy and establishing best practices. It may also raise awareness to situations that have remained invisible for too long. "I would love to be out of a job because we're no longer doing terrible things in the same way," Shlafer says.

This is the penultimate paragraph in the story, the narrative tidying up that will set up a satisfying, concluding coda, ideally with a quote from the main subject. But the more you look at the experiences of women while incarcerated right now, the less you feel you have a strong grasp on the situation. Like space suits and military gear, prisons weren't designed or created with women in mind. And while there is a movement to rethink the prison to accommodate women's needs better, Sufrin's research drives her toward conflicting realizations. We need to provide incarcerated women with better care. And we need to stop relying on incarceration to hide the problems of poverty, substance abuse, and racial oppression from public view.

Researchers trying to shed light on these issues find themselves straddling two worlds that systemically don't want to overlap. Advocating for health and well-being in a space of punishment "creates the central tension in how I approach my work and where I see myself and my commitments," Sufrin says. "Overall I support decarceration. But until that day comes, people need health care, and that's what I can do. I can provide guidance on best practices so that people are getting the health care that they deserve constitutionally and so that we're not harming them in the process."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged public health, pregnancy, incarceration