Since 2000, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, a project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has collected data to make an official estimate of all children living with developmental disorders in the United States.

But the network has historically tracked children with autism spectrum disorder only until age 8, leaving researchers with a field of questions about how the disorder presents itself in adolescence and adulthood, and how support programs in schools and communities are able to meet changing needs.

Image credit: Kumé Pather

This January, the ADDM Network announced that—for the first time—it would begin tracking the mental and physical health of teenagers with ASD at four sites, including at Johns Hopkins.

"The new grant will allow us to fill in the gaps surrounding the trajectory [of those with ASD] between ages 8 and 16. How do they utilize health care services? How are they doing in school? How is their mental health? How independent are they?" says epidemiologist Li-Ching Lee, principal investigator of the ADDM Network's Maryland site, located at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. "We also want to know about their emergency department visits, their hospitalizations, suicidal behaviors, and the suicide rate among teens with ASD."

By mining school and medical records, the expanded tracking paves the way for major breakthroughs in treatment and social support systems for those with ASD, which in 2015 cost an estimated $268 billion and is projected to rise to $461 billion by 2025, according to the nonprofit Autism Speaks. By following up with the children who were last tracked by the network in 2010 when they were 8 years old, researchers hope to understand how best to prepare teens for the "service cliff," a term for the drop-off in services that happens as they age out of school-based programs, and whether current support systems meet their needs.

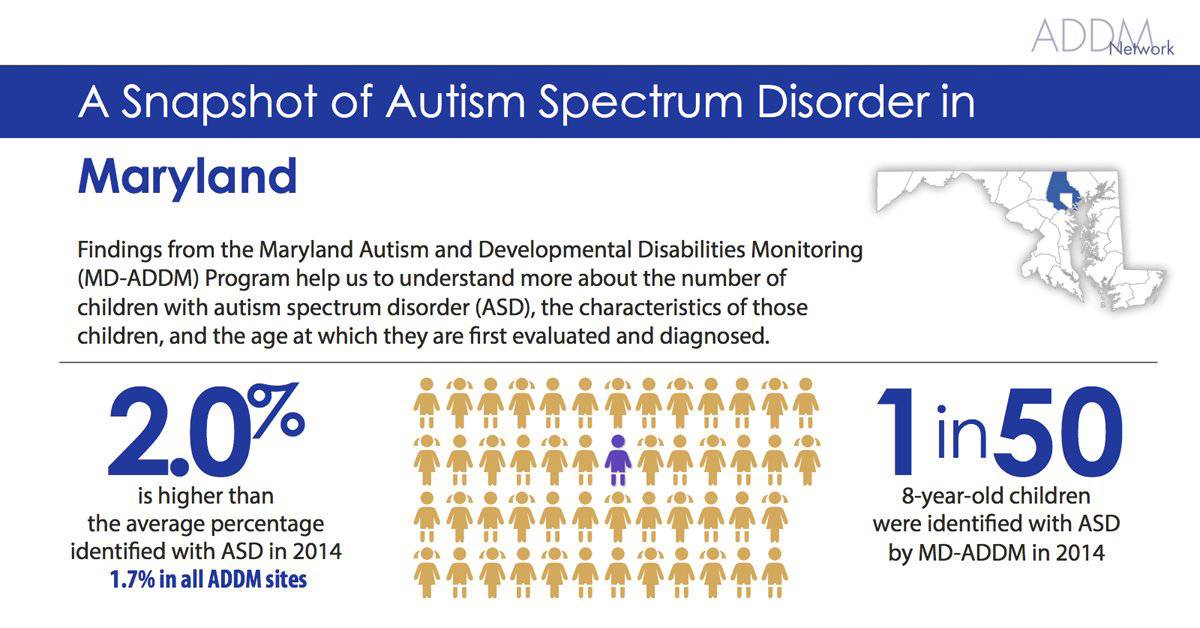

Image caption: Facts from the Bloomberg school's prevalence report from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Network.

Take teen suicide rates, which research indicates are higher in teens with ASD. Are there patterns that indicate other concurrent mental health issues might be at play, or are the higher rates "due to the fact these teens didn't get the proper [autism-related] care or support they needed?" Lee asks.

Answers are still years away. The ADDM Network's first insights into autism in teens will likely be released in 2022 and 2024. But the goal, Lee says, is to identify the biggest needs of teens with autism in a series of "community reports" with recommendations tailored for key stakeholders—policymakers, schools, communities, and parents of teens with ASD—to make lasting change.

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged autism, child development