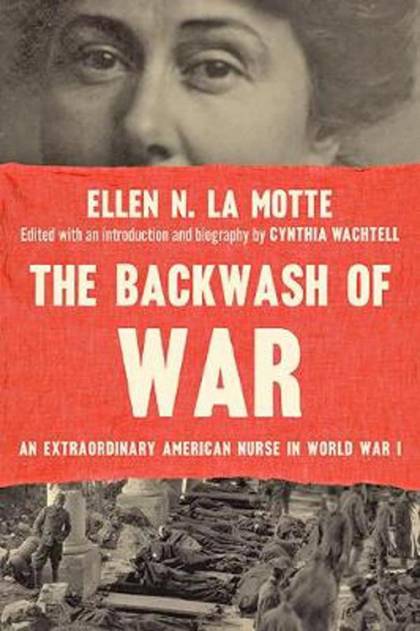

Ellen N. La Motte is the most important war writer in English you've probably never heard of, says Cynthia Wachtell, who recently published a new edition of La Motte's World War I stories drawn from her experience nursing near the front lines.

Image caption: The new edition of Ellen La Motte’s Backwash of War contains the first extended biography of the trailblazing writer

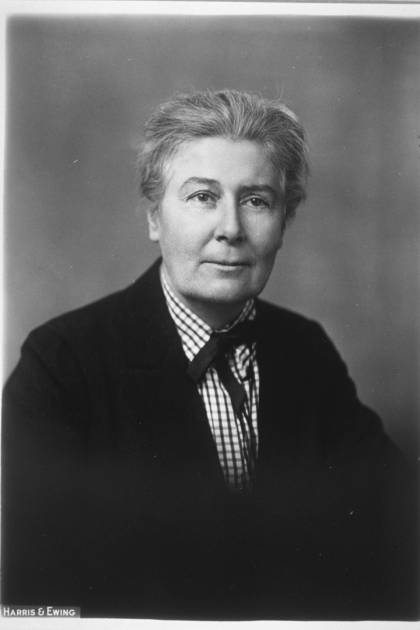

Image credit: Harris & Ewing

Having studied nursing at Johns Hopkins despite her prominent family's objections, La Motte, Nurs 1902 (Cert), led a campaign against tuberculosis in Baltimore's slums, became the city's first female head of a health department division, penned public health articles, and agitated for women's enfranchisement. In 1913, newspapers announced her plan to join the British suffragettes as an activist-journalist; her articles for The Baltimore Sun reflect wit and admiration for the suffragettes' militancy. Relocating to Paris later that year, she authored a textbook on tuberculosis nursing and forged a deep friendship with Baltimore expatriate and avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein. Then the Great War began.

Posthaste, La Motte volunteered her services. Her experience at a French military field hospital just behind the front lines in Belgium would become the substance of a story collection, The Backwash of War: The Human Wreckage of the Battlefield as Witnessed by an American Hospital Nurse, first published in September 1916, seven months before the United States entered World War I.

Suppressed immediately in England and France, La Motte's harrowing depiction of wartime conditions was hailed in America as "literary high explosives," selling well enough to merit four printings in two years. A Los Angeles Times reviewer called it "the first realistic glimpse behind the battle lines that has been offered to a neutral public" and avowed that "if we were to compile an anthology of the ten best war stories, about eight of them would be listed under the name of Ellen N. La Motte and credited to The Backwash of War." The book circulated until August 1918, when the publisher withdrew it at the postmaster general's request. The Espionage Act of 1917 permitted censorship of materials that could "embarrass or hamper the Government in conducting the war."

Reissued after the war, and again in 1934, the book, and its author with it, nevertheless slipped into obscurity and missed their rightful place in the canon, says Wachtell, a research associate professor of American studies at Yeshiva University. She discovered La Motte in the early '90s while writing her dissertation on the history of American anti-war literature and was "blown away" by the writing, which seemed to belong to a later time. But secondary source material was scarce. No one was studying her. "It mystified me that her work was so unknown—lost to history."

In editing the new scholarly edition of Backwash, published in February by Johns Hopkins University Press, Wachtell added illuminating introductory and biographical essays robustly researched from primary sources; a bibliography; timeline; photographs; and three wartime essays by La Motte. Wachtell's investigation took her to some 20 archives, including Johns Hopkins' Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, where she found not only La Motte's application to Hopkins but a collection of 16 letters from La Motte to friend Amy Wesselhoeft von Erdberg, discovered in a German hayloft and donated in 2013. Wachtell is La Motte's first biographer.

More than a century after its appearance, Backwash remains a truth bomb. Everywhere in its pages, pain and death are hideous, sometimes ludicrous, never romantic or redemptive. Men die in surgery, and they die in agony. Gangrene and fistulas reek. A soldier who has botched his suicide attempt is nursed back toward health, against his will, to be shot as a deserter. Many times in La Motte's account, "the science of healing [stands] baffled before the science of destroying." The grotesque wounds wrought by bullet and shrapnel, under examination by a skilled nurse, administrator, and reformer, also reveal the social ills that give rise to such suffering.

Society's civilized structures crumble like houses under shell fire, while its injustices endure. Army policy forbids wives but encourages prostitution. In a passage that anticipates Orwell, La Motte deadpans, "Ah yes, France is democratic. It is the Nation's war, and all the men of the Nation, regardless of rank, are serving. But some serve in better places than others. The trenches are mostly reserved for men of the working class, which is reasonable, as there are more of them."

Backwash preceded Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front and Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms by more than a decade. "To the extent that later writers, like Vonnegut, Heller, Tim O'Brien were building on this anti-war tradition—the sense of irony, of jadedness, of disillusionment—they were really building on her work, whether they were individually aware of that or not," Wachtell says.

After Backwash, La Motte toured Asia with her partner, Emily Crane Chadbourne. Turning her keen eye on the opium trade and its exploitation by colonial powers, she embarked on an uphill crusade that would occupy her for the rest of her career. Her critique of opioid profiteering by the powerful—"bad faith," in a nutshell—has enduring relevance, Wachtell notes.

Others, mostly men, would assume the mantle of "war writer." Ernest Hemingway, for one, may have read La Motte as a teenager, before signing up as an ambulance driver in Europe. La Motte's close friend Gertrude Stein would later become his mentor.

"It's impossible to think that when Stein was teaching Hemingway how to write about war, she's not to some extent thinking about Ellen La Motte," says Wachtell. "When Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize in the 1950s, it was for 'the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style,' but La Motte was first and was much more bold than the postwar writers," Wachtell explains. "She was taking a much greater risk because she wrote during the war, not after the war, when disillusionment had already set in. She wrote at a time when it was absolutely unacceptable to criticize the war. That's why her book was banned in multiple countries. ... And yet, she gets none of the credit. She was not just braver and bolder; she was the innovator. She was showing them the way."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged literature, school of nursing