In a cramped workroom at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, a team of six—one second-year resident, two interns, and three medical students—feverishly enter diagnostic information at computer terminals and confer about medication dosage. Just another typical pre-rounds Tuesday morning.

In particular, this team's focus is turned today to a woman in her 30s who's dealing with a litany of chronic conditions and had been admitted to the hospital weeks ago owing to complications from organ failure. They've recommended she undergo a procedure to determine the root cause of what brought her into the hospital, but the patient has refused because of serious side effects from a previous experience.

But now, the team is told to press pause on all things treatment-related—and take an art appreciation timeout.

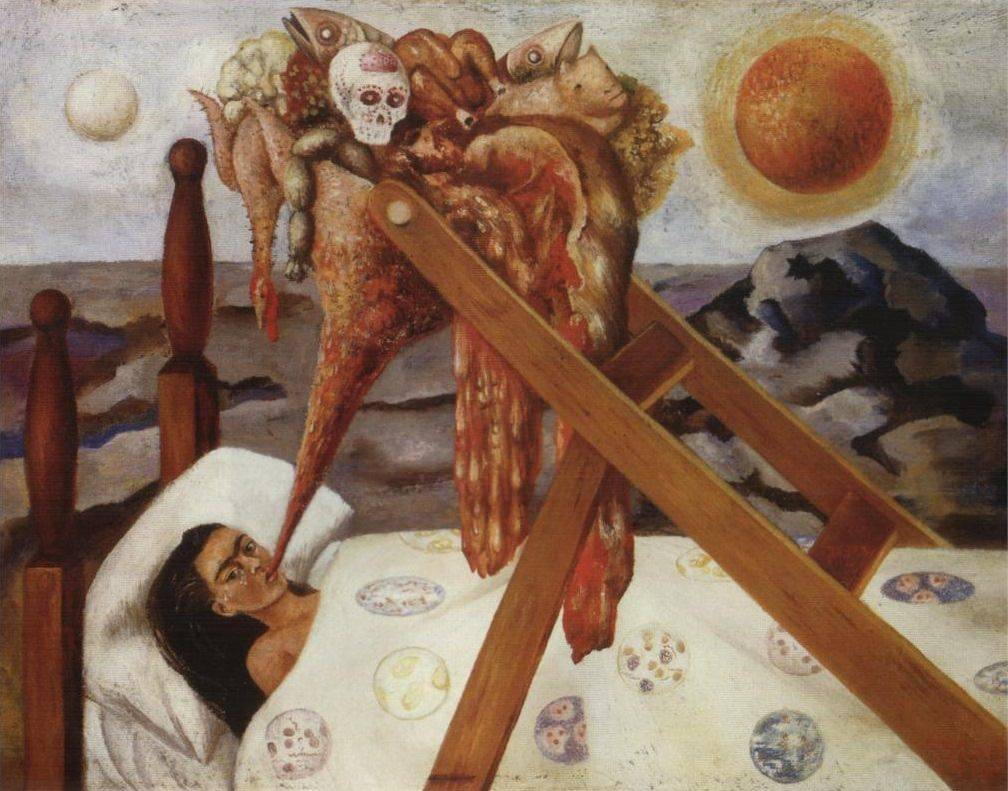

Christiana "Tina" Zhang, a post-doctoral fellow in general internal medicine and the team's attending physician, clicks her laptop keyboard to reveal an image of the Frida Kahlo painting Without Hope. In the painting, Kahlo—who herself had numerous illnesses at the time—lies in a bed set in a desert landscape with a long funnel pointing toward her mouth and overflowing with a grotesque, reddish conglomeration of fish, chicken, sausages, lamb, and a Mexican sugar skull. The sun and the moon hang in the sky.

"Take a few minutes to tell me what you see in the painting, and then how it applies" to the patient, Zhang says.

One by one, team members chime in with descriptions, searching for meaning in the imagery. Several focus on the directionality of the funnel, and wonder whether the menagerie of yuck is being funneled out of her mouth or into her. Was this a case of force-feeding? Someone points out most of "the action" goes on above Kahlo, while she remains tightly confined under sheets with only her shoulder exposed, representing a sense of powerlessness and vulnerability. Another comments on the barren desert landscape, devoid of anything reassuring, and that the sun and moon could impart a sense of timelessness, like a patient in an extended hospital stay who doesn't know whether it's night or day.

Nobody notices, until Zhang points it out, that the woman in the painting has tears streaming down her face.

"I didn't see she was crying," says Sina Famenini, a third-year medical student. "I was looking at everything else in the painting, and here she's lying there crying. I didn't see her for who she is."

This art session was a demonstration of BEAM—short for Bedside Education in the Art of Medicine—a project created by Margaret Chisolm and Susan Lehmann in the School of Medicine's Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences as a way to foster empathy with patients. BEAM, currently in pilot phase, is a mobile app inspired by Quaker teacher Parker J. Palmer's pedagogical approach of a "third thing," where images or an object can serve as icebreaker between two parties to create a safe space for difficult topics of conversation. In this case, the third things are public domain paintings, photographs, and poems that can be searched by artist, title, and theme such as pain, loneliness, joy, fear, dying, and hopelessness.

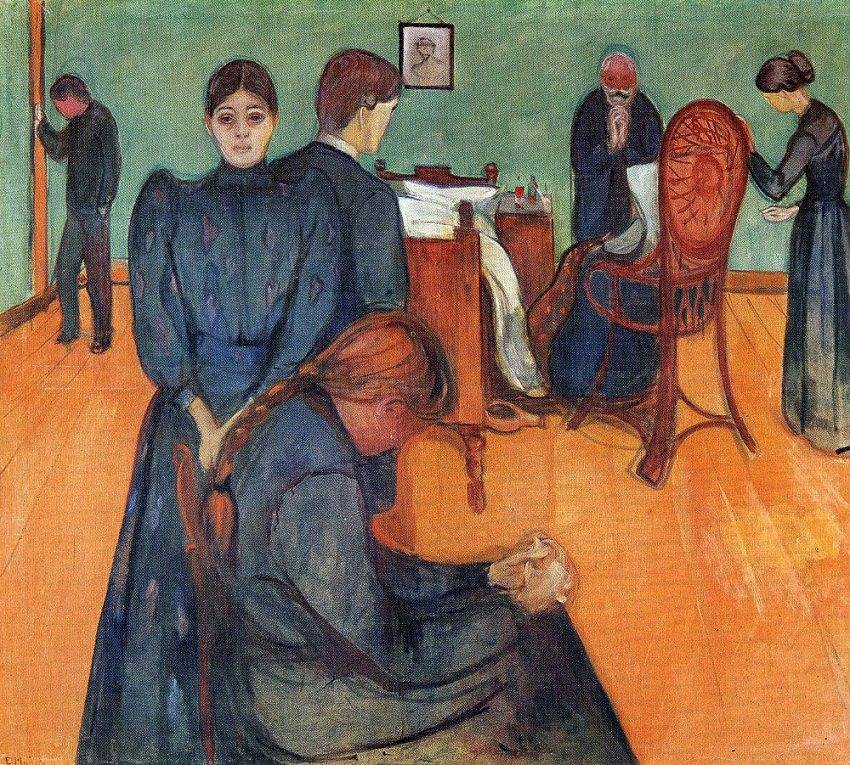

Image caption:Death in the Sickroom by Edvard Munch is one of the pieces available on the BEAM website

"These works can serve to grease the skids, and get a meaningful conversation going," Chisolm says. "Our hope is that it not just brings the medical team closer together but the team closer with the patient as well."

In the first BEAM demo earlier this year, Zhang used Edward Hopper's Nighthawks painting to discuss the case of a blind patient who had been widowed for nearly two decades. The caregiving team had gotten together several times to confer about the patient's disease progression and treatment, but for those few minutes they contemplated lonely figures in a late night diner. Zhang, who admits she was initially skeptical about the prospect of using a painting or poem to discuss a patient's care, says the Nighthawks discussion gave her chills as the group considered what it meant to be truly alone.

"We got talking more about the social side of this man's life and how we could help him outside the hospital, rather than just treat his medical problems," she says. "This changed our interaction with him from that point on. We spent more time with him and learned details about his social life, and we were very conscious of this as we developed a safe discharge plan for him."

Multiple recent studies have shown that there is decreased empathy and increased burnout among medical students and residents nationwide, as medicine has become increasingly focused on technological advances. And young learners are often asked to work long shifts and shuttle between numerous patients, making it a challenge to develop in-depth relationships. Several other studies have shown that art can be an effective tool to both foster empathy and improve observation skills, which have been linked with improved patient outcomes.

Chisholm says the BEAM experience creates a dedicated time to sit down in the middle of a busy day and talk about patients in terms of the whole person, not just as vessels with symptoms and pathologies but individuals with emotions and a backstory. She has long championed the use of digital technology and arts and humanities to make medicine more personal. In addition to BEAM, Chisolm recently created an elective for fourth-year medical students that includes twice-weekly visits to the Baltimore Museum of Art and the American Visionary Art Museum to use art to explore what it means to be human and a good physician. She's also a co-developer of the Closler website, a project of the Miller Coulson Academy of Clinical Excellence that encourages Johns Hopkins caregivers to share stories that highlight the personal side of patient care.

Currently, the BEAM website and associated app have only a handful of works of art, but the site has a capacity for thousands of images, texts, and musical works. After the pilot study and proof of concept, conducted at Bayview Medical Center, the plan is to tweak the app as necessary and then make it free and publicly available.

At the end of the demonstration at Bayview, Zhang asks the group what they thought of the experience.

"For me, it was good to reframe my thinking of our patients," says Evans Brown, a second-year resident. "And specifically with this painting, I thought about the therapies that we're offering and how, even if they seem like from the medical perspective it's the right thing to do, from the patient's perspective there is so much more to consider."

Armed with a fresh perspective, the team is ready for morning rounds to begin.

Posted in Health, Arts+Culture