In September 2012, journalist Rachel Monroe was lying on a mattress on the floor of an artists' warehouse in Baltimore when she wandered into the online community of young girls obsessed with two teenage murderers. On the microblogging site Tumblr, Monroe came across page after page after page of photos of these two teen killers surrounded by digitally drawn hearts. She saw mash notes quoting from their diaries. She read fan fiction that imagined their lives. She was immersed in teenage girls' expressing their monumental teenage girl feelings for two boys who had killed their high school peers. And Monroe fell into this internet wormhole because yet another teenage boy had gone to school armed.

That summer night, Monroe, A&S '09 (MFA), was cycling through the "What am I even doing?" second guessing typical of late-20-something life. She had finished her fiction MFA shortly after the financial crash, and after a few years of adjunct teaching and writing for a Baltimore website, she was moving to Marfa, Texas, a place she fell in love with after spending a few weeks there during a cross-country trip. She sold most of her furniture, and packed what remained into boxes. And as she lay in her nearly empty room, she read something online about a 15-year-old high school student in a northern Baltimore suburb. He rode the bus to school. He attended his first and second periods. He went to lunch. Then he went into the bathroom to assemble his father's Western Field double-barrel shotgun and 21 rounds of 16-gauge shells before returning to the cafeteria to open fire.

A special-needs student was hit by one of two shots fired before the teenager was subdued by a school counselor. Monroe needed to know more. She started Googling the shooter and didn't find much: a Baltimore Sun news story; what he had posted to his social media accounts, such as "First day of school, last day of my life"; and listing "The Manson Family" as his employer. "I just had that feeling of, I want to know what is up with this kid," Monroe tells me during an interview in Baltimore in May. What little information she did find led her to Tumblr, where young people were talking about it and hoping the shooter wasn't a Columbiner.

Image credit: Chris Visions

A what? "When I found what that whole world was like, I just thought, Whoa," Monroe says of the pages of user-generated content devoted to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold fandom, the two teens who killed 12 of their classmates and one teacher at Columbine High School in 1999. When mainstream media talks about the online enthusiasm for murderers among young people, the focus is typically what we've depressingly come to expect following mass shootings in America: the disturbing mental states of young white men who commit atrocious acts of violence.

Less common is the emotional immensity that teenage girls bring to their Columbine fascination that Monroe zeroed in on in her 2012 essay for The Awl website titled "The Killer Crush: The Horror of Teen Girls, From Columbiners to Beliebers." Just as shocking as the puffy paint ways these girls expressed their Harris and Klebold adoration—sample quote: "I think the only place I'll ever really feel complete is with Eric and Dylan amongst the stars?"—was how easily Monroe understood it. It wasn't all that different from her teenage crush on Gavin Rossdale of the band Bush or her aunt nearly screaming herself faint for the Beatles in 1966. Teen girl sexuality, Monroe wrote in that essay, "can edge up against the dark and the illogical, even when the crush object isn't a murderer. What's more disconcerting, perhaps, is being confronted with what teen girls, or a subset of teen girls, really want."

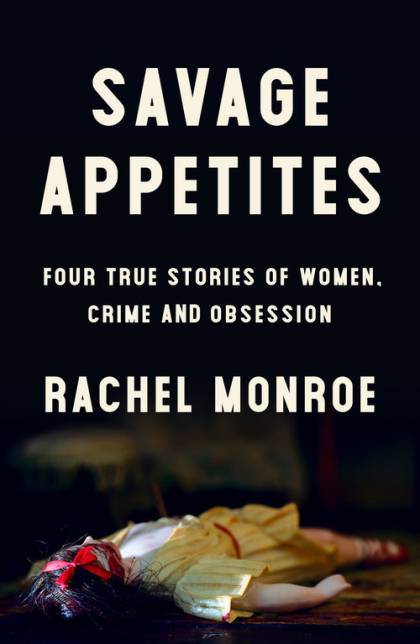

Image credit: Scribner

Monroe understood crime's allure. In her new, debut book, Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession (Scribner), she admits she's been murder-minded ever since she was a kid. Growing up, she read People magazine only for its stories about missing kids. Her early teen reads included paperback true crime staples such as Ann Rule's The Stranger Beside Me, about Rule's relationship with Ted Bundy, and Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry's Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders. She trades emails with her mom about serial killers. As an undergrad at Pomona College in California, she followed online news coverage about a missing girl in her native Richmond, Virginia. In Baltimore, she became obsessed with the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, 19 painstakingly constructed dioramas of murder scenes housed at the Maryland Medical Examiner's Office and used to teach forensic investigation.

It wasn't murder, specifically, that arrested her imagination, but the extreme emotional states that came from thinking about it: What are people actually capable of? Monroe realized she would fall into these "crime funks" when she was going through intense moments in her own life—like, say, preparing to move 1,880 miles across the country. "These stories tend to snag me at these points when my life feels like it's spinning out of control," she says, adding that when they hit, she spends a few nights, weeks, or months fixated on them. "It was only around when I moved to Marfa seven years ago that I realized I could write about these fascinations."

Savage is the result of her fascination with women who become obsessed with murders that don't directly affect them, and it's a sneaky tour de force. Part memoir, part journalism, part social history, and completely addictive, the book intertwines Monroe's own obsessions with those of the four women she profiles. And each woman's interest in murder corresponds to a different aspect of the crime. In the 1940s and 1950s, heiress Frances Glessner Lee helped kick-start the field of forensic science by making outlandishly intricate and to-scale models of murder scenes that became the Nutshell Studies. She's the detective. In 1990, aspiring film director Alisa Statman moved into the Cielo Drive cottage where some of the Manson murders took place and began to insinuate herself into the family of Sharon Tate, eventually co-writing Restless Souls: The Sharon Tate Family's Account of Stardom, the Manson Murders, and a Crusade for Justice with Tate's niece. She represents the victim.

Landscape architect Lorri Davis became so transfixed by the 1996 documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills about the West Memphis Three that she began corresponding with one of the convicted, Damien Echols, left her life in New York and moved to Arkansas, became an advocate for his exoneration, and married Echols in 1999. She represents the defender. And in 2014 Lindsay Souvannarath was just an average 23-year-old suburban American woman who felt more herself online than in real life until she met a fellow socially awkward young man and they began planning their own murder-suicide mass shooting. She's the killer.

Image caption: Rachel Monroe

Image credit: Emma Rogers

These women's stories are interspersed with the development of forensic science in America, the rise of the idea of victim's rights, how the Satanic Panic of the 1980s reinforced class lines in America, how Columbine became a media spectacle, and how gender plays out in all of the above. Buzzing in the background of the entire book is that condescendingly simplistic question that mainstream media has asked again and again during the recent boom in true crime and crime fiction books, podcasts, television series, and movies, et cetera: Why are the audiences for these things so overwhelmingly female?

Savage is less interested in why women consume true crime than it is in women themselves, and that subtle pivot allows Monroe to explore a more unnerving question: What are women actually capable of? "I started from these questions that wouldn't go away, and then I felt them out and reached some sort of preliminary and overlapping conclusions," Monroe says of writing the book over two years, though she'd been thinking about it for a decade. "It really was one of the situations where you're walking down a path and then you look back and realize, Oh, this is where I've been heading."

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when the current flood of true crime programming started, though a few titles mark the time period when crime stories entered wider popular consciousness. A string of "girl" thrillers—such as Stieg Larsson's novel The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (English translation 2008), its 2009 film adaptation and 2011 American remake; Gillian Flynn's novel Gone Girl (2012) and its 2014 film adaptation; Paula Hawkins' novel The Girl on a Train (2015) and its 2016 film—took over crime fiction and movies. In 2014, Sarah Koenig's Serial podcast debuted, followed by a number of other addictive true crime series such as the HBO documentary The Jinx and Netflix's Making a Murderer and The Keepers.

Now, humans have always harbored a gruesome interest in murder stories. Women, however, are touted as driving this current true crime spree. In 2017 the marketing research firm Edison Research noted that 56 percent of all podcast listeners are male, but the social media monitoring company Brandwatch identified that women listened to true crime podcasts more than men, often dramatically so. In 2017, the Oxygen cable network, created in 2000 to focus on women's programming, rebranded itself as a true crime–focused network, and a broadcast business magazine noted that advertisers wanting to reach women flocked to it. This true crime boom, notably, has unfolded over a period when national murder rates are trending downward from the highs of the 1980s to mid-1990s and, statistically speaking, women—and white women in particular—are the least likely to be either murder victims or offenders.

Also see

Why women are so drawn to it became a matter for think-piece pondering. In 2017, social psychologist Amanda Vicary told The Atlantic that women's true crime interest may be evolutionary: "We've adapted to pay attention to anything that can help us increase our survival. So it could be the fact that we're just in tune and interested in these things that are dangerous to us because understanding and knowing about them can increase our chances that it's not going to happen to us."

She had some science to back up her claim. In 2010, Vicary co-authored "Captured by True Crime: Why Are Woman Drawn to Tales of Rape, Murder and Serial Killers," published in the inaugural issue of Social Psychological and Personality Science, which examined women's interest in and response to true crime books. It discovered that more than 70% of the true crime book reviews on Amazon were by women, and argued that women's interest in true crime books about women victims suggests that they "may be attracted to these books because of the potential lifesaving knowledge gained from reading them."

Monroe finds this reasoning utterly unconvincing. "While I don't deny that that is a piece of the pie, it seemed to me such an incomplete and really tone-deaf explanation," she says. She notes that Vicary's study also determined that men overwhelmingly read more war books than women. Does that mean that men read them so if they go to war they can avoid getting killed?

"Women's interests already exist in narrow categories, and so many things about women are policed," she says, highlighting the assumption that if a woman is interested in unsettling subject matter, it must be for virtuous, feminine reasons. "And to me that explanation doesn't address, frankly, the appetite for it. There's a reason that word is in the book's title. People binge these stories. It's not like it's oatmeal that you're eating to fortify you for the day. There's clearly more going on there in ways that I think are maybe more unsettling or less flattering."

It's Monroe's restless interest in contextualizing the messiness of women's appetites that gives Savage its lasting power. In "The Detective" section she explores women's entry into the ranks of U.S. law enforcement over the 20th century while documenting Frances Glessner Lee's foray into miniature murder scenes, piecing together a portrait of the changing nature of police work. Throughout this section, Monroe talks about her middle school readings of Patricia Cornwell's best-selling novels involving medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, who is based in Monroe's native Richmond early in the series. These overlapping threads stitch together a history of what kinds of work women are permitted to do in crime investigation with Monroe's understanding that becoming a "woman" in America meant acquiring a kind of sexual power that was also a vulnerability.

She continues this threading of personal and social narratives throughout the book, spotlighting the ways in which discussions of women's current interests in and obsessions for true crime programming are based on long-held assumptions about what women's roles are or should be. What Savage most reminded me of wasn't any other true crime opus but anthropologist Emily Martin's 1991 journal article "The Egg and the Sperm," which outlined how the language of reproductive biology textbooks uses cultural notions of "masculinity" and "femininity" to present ostensible science facts. Monroe demonstrates how cultural assumptions about gender, race, and class shape what we think we know about crime. She shows how true crime discussions often reduce women to mere consumers, a market demand to be supplied with programming, and have little interest in what women have to say.

And women, if asked, will point out that their criminal interests aren't new. In 2018 The Sewanee Review had crime novelist Megan Abbott comment about the "recent" success of women thrillers such as Gone Girl: "Yet these books have always existed. Shirley Jackson in the 1950s, Daphne du Maurier in the '30s and '40s—all the way back to, say, Charlotte Perkins Gilman's story 'The Yellow Wallpaper,' or the Bronte?s. These are quite subversive works, filled with complicated notions of female desire and often full of female rage."

In the late 1990s a balding, portly, middle-aged man living in Texas wanted to die. He'd met some young people while going to raves in and around Austin and San Antonio, and he'd sometimes ask one of them if they'd help him do just that. In early 2000, someone finally said yes.

"Have You Ever Thought About Killing Someone?," Monroe's 2015 piece for the website Matter, is an elliptical, lyrical feature about Mike Baker strangling Shannon Roberts in Big Bend National Park, the police and FBI investigation, and his ultimate plea deal for second-degree murder. It was a finalist in the 2016 Livingston Award for National Reporting. For it, the murder-minded Monroe interviewed a murderer for the first time.

She recalls a feeling she had during her reporting. She was driving back to Marfa from Big Bend, where she'd spent the day going through the local law enforcement's Baker files. At that point she had been speaking with Baker for about a year, and he had told her things he didn't tell the police. She had talked with Baker's friends, who told her things they didn't tell the police or Baker. And now she had Baker's police file.

"It was sunset, and I was driving in this total high where I was thinking, I know more about this story probably than literally anybody alive," she recalls, her momentary reporter's euphoria punctured by the shock of her dangerous arrogance. "It was a really striking moment, and I had to remind myself, This did not happen to me. I was not there. There is a lot that I don't know. There's a lot that I will never know. Just be careful about that."

Every reporter knows information can be intoxicating but getting drunk on it can lead to ruin. The fiction-schooled Monroe says she naturally thinks like a fiction writer, gravitating toward using scenes, textural details, and emotional shifts, layers that she brings to her features reporting that's appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The Believer over the past seven years. Savage showcases Monroe as a polyphonic writer—see also: Maggie Nelson, Wendy C. Ortiz, Elena Passarello—for whom the nonfiction essay/book is a vehicle for erasing the borders that divide writing into genres, separate poetry from prose, and confine the first-person to memoir instead of permitting it to wade through the wider world of ideas. Confronting your own misconceptions is part of the learning process.

In Savage, Monroe touches on that aspect most poignantly in "The Killer" section, where she writes about Lindsay Souvannarath. In 2014 Souvannarath was a 23-year-old college dropout living with her parents in suburban Chicago when she met James Gamble via Tumblr. Gamble, 19, lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and shared her interest in Columbine and racist neo-Nazi beliefs.

Over a period of weeks from the end of 2014 to early 2105, Souvannarath and Gamble coordinated a plan for meeting up and going out. She'd fly to Halifax, where one of Gamble's friends would pick her up and take her to Gamble's home. They'd consummate their online relationship and then take his father's .308 rifle and 16-gauge shotgun to the Halifax Shopping Centre. It was to take place on February 14, 2015.

Crime Stoppers alerted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to a threat in the Halifax area; the police picked up Souvannarath and staked out Gamble's home. He turned one of the firearms on himself. Souvannarath pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy to commit murder and conspiracy to commit arson, and is currently serving a life sentence with no possibility of parole for 10 years.

This case was modestly covered, if at all, by American media, and mostly in the Chicago area. Monroe heard about it through the Columbiners community on Tumblr, and reporting on Souvannarath forced Monroe to revisit the Columbiners with new eyes. "When you're reporting, you're having these face-to-face moments with people who have gone through this terrible thing," she says. Reporting on murders "has made me think more carefully about that realm because my whole first take was, 'Oh, the Columbiners, it's this kind of harmless working out of things—they're not literally wanting to kill people.'"

Savage unflinchingly centers what all the talk about women's interest in true crimes doesn't: that violent crime entertainments enable us to ignore the realities of violent crimes, which in America are much more likely to involve the murder of young black men, violence against sex workers, and intimate partner violence. True crime and crime fiction make investigators of its audience, though they never have to cold call somebody to ask about a family member who's been murdered. True crime and crime fiction allow the upheaval of crime to acquire the illusion of justice, when, as Monroe told me, "the court system is supposed to give us an answer or closure or finality, and it isn't capable of doing that." True crime stories allow us to acknowledge that violent crime exists while doing nothing to change the lives of people most affected by them.

Murder is messier, stranger, uglier, and more ordinary than true crime entertainments are prepared to admit because the human stories continue after our savage appetites are sated. "We're still in touch," Monroe says of Mike Baker, who is out of jail now and lives in Midland, Texas, where he works in an oil field. He texts Monroe every few months, and recently told her he had adopted an extremely floofy dog. Monroe says she jazzed him about so totally loving his little dog. She asked, What's the dog's name? "And he replied, 'Cookie.'"

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged sociology, entertainment, crime