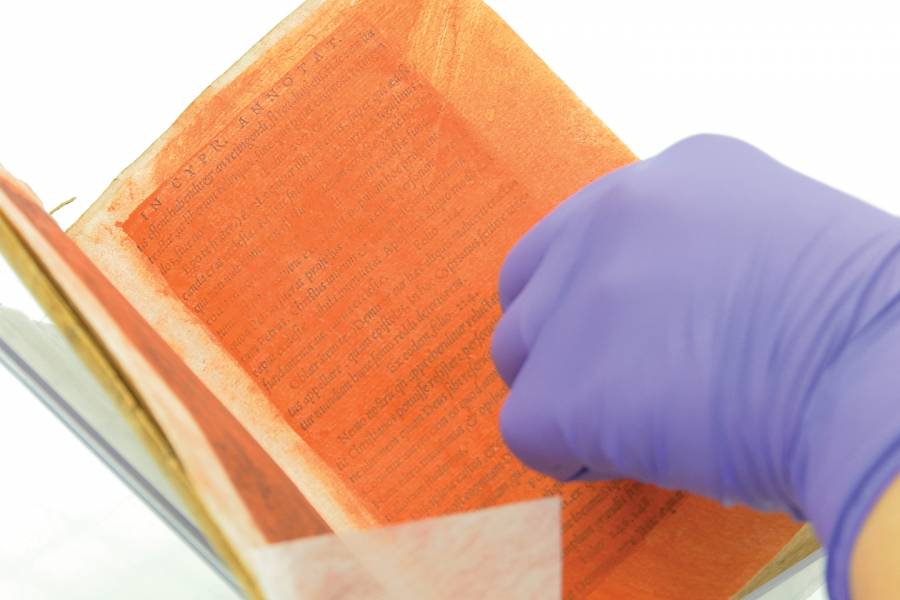

Earle Havens, curator of rare books and manuscripts for the Sheridan Libraries, happened upon the volume on an antiquarian bookseller's listings. The book—The Works of St. Cyprian, a third-century martyr, bishop of Carthage, and a father of early Christianity—is small but thick, with soft-worn and yellowed goatskin parchment covers. Its 19-page preface, written centuries later by the Renaissance scholar Desiderius Erasmus, had been covered by haphazard slathers of red and black paint.

Havens immediately put in an offer. "I've certainly seen my share of expurgated books, books that have canceled lines, usually with ink," he says. "But never anything quite on this scale of actually obliterating the text with a kind of opaque red paint."

The curator sent his new purchase for repair of its loose pages to the libraries' conservation lab, where it was seen by Patty McGuiggan, Heritage Science for Conservation laboratory's principal investigator and an associate research professor in Materials Science and Engineering. She wondered what was beneath the layers. "And, of course, you can't just wipe away or erase the paint because then it would not be special," she says.

Now, thanks to a $100,000 Johns Hopkins Discovery Award, McGuiggan and her team—with backgrounds in not just conservation but big data analytics and astronomy—will use complex imaging processes and other methods to try to see beneath the paint.

"This is definitely something out of the ordinary from what I'd normally do," says Johns Hopkins astrophysicist Alex Szalay, whose career has largely focused on measuring patterns in the distribution of galaxies. His expertise with big data and complex image processing will help the team examine numerous high-resolution images containing only slight variations between them.

The Red Cyprian, as Havens refers to it, was printed in Venice in 1547. Erasmus edited and annotated the text and wrote the preface, where he thanks the church for its patronage of his early scholarship. A lifelong Catholic, Erasmus became a vocal advocate for reform within the church, encouraging people to have a more direct relationship with God—which may have led believers to sidestep the church's role as the intercessor between man and God. Erasmus and Cyprian professed somewhat parallel beliefs, Havens says, "trying to go back to this model of Jesus Christ and the apostles, and the church was trying to put the genie back in the bottle by eliminating the legibility of that information."

In an attempt to quash calls for reform, the church eventually deemed Erasmus a heretic, listing his work on the Index of Prohibited Books. The Red Cyprian, then, is a time capsule, taking us "back through all these different layers of thought, and even in the destructive force of censorship, we learn things about how these ideas lived in the world," Havens says.

Image credit: Dave Schmelick

What the preface text actually says, however, is not entirely a mystery. Unexpurgated editions of the book exist; the Sheridan Libraries even own one. But that doesn't nullify the unusual censorship or the desire to learn more about the book using scientific processes—it may even be helpful to check against their findings, says Andrea Hall, senior research specialist for Heritage Science for Conservation.

Because of the book's fragility—and the toxic mercury, lead, and arsenic detected in the red pigments—Jennifer Jarvis, a Johns Hopkins book and paper conservator, was brought on to ensure the team handles the book safely. She'll also lend her expertise on the book's artifactual evidence, i.e., its paper and sewing and binding structures. Understanding these elements in the context of what was commonly done at that time helps Jarvis locate where and when the book was constructed, information that guides the team as they dig into hypotheses about the censorship.

"I ordinarily never wear gloves when I handle books because it impedes your sense of touch," Jarvis says, her gloved hands carefully paging through the preface, noting where the pigment appears to have flaked off into the book's gutter. In some areas, the red is opaque as well as blacked out; in others it's translucent enough to read through.

Imaging and analysis may reveal more about the pigments and their application. The team will try something called hyperspectral imaging, shining bands of light, from ultraviolet to infrared, at varied wavelengths on the pages. Because red lead becomes transparent under infrared light, imaging that pigment under infrared will make legible the carbon black ink text underneath. But the carbon black pigment that covers the carbon black text poses more of a challenge.

After the imaging, Szalay and Tama?s Budava?ri, an associate professor in Applied Mathematics and Statistics, will enhance and analyze the results. If any pages are too choked with noise—grainy, fuzzy, indecipherable distortion—to read, the two may be able to compare and match patterns between the book's muddled and more legible characters. "From that, one could look at the alphabet, one could look at the words being used, one could look at the different stylistic patterns" to make a more educated guess as to what the paint obscures, Budava?ri says.

Right now, the team's path ahead is about as clear as the preface's text; the process will likely lead to unforeseen challenges and questions. "One of the problems is that I might want to pull it apart, right? To really see," McGuiggan says. "And I can't do that. So it could be, in the end, some stuff is just going to be a mystery."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged sheridan libraries, materials science