Recently, I had to sort through boxes of my own juvenilia that had been sitting in the attic of my childhood home, to salvage anything I wanted before Mom hauled them all to a landfill. Among the vintage purple-inked dittos, field trip permission slips, lunch menus from 1973, and advertising circulars for bell-bottoms and leisure suits, I found a copy of my second-grade class photo. Scanning those three rows of kids in corduroy and plaid, I found that after 35 years the name of almost every classmate was still stored in my brain, as untouched as all those dittos in the attic; the roster came back to me as automatically as the lyrics to "Jesus Loves Me." To someone whose memory has been cluttered with thousands of sitcom episodes and gutted by drink, it was like discovering I still had a kid's ability to climb trees or make imaginary friends.

As I look at this picture now, the dissonance between perception and memory creates a weird double-exposure effect. Because I'm an adult, I can see these people for what they are—little kids, 7 or 8 years old. But I also see them, more vividly, as they were to me then—peers, other people in my world, as real and to be reckoned with as your co-workers are to you now. They were friends and enemies, cutups and bullies, flirts, bores, ciphers, and complete assholes. It still takes a perceptual effort, a kind of mental squinting, to see our teacher as a pert, not unpretty woman, younger than I am now, instead of the martinet who sent me to the vice principal's office for talking during Reading.

In the same way, when I look at Phoebe sitting there in the front row, someone I haven't thought of once in 35 years, what I objectively see—a 7-year-old girl—is imperfectly superimposed over the person I knew. What I really think when I look at her, my eyes narrowing, is: You. Phoebe was my nemesis. We were the leaders of our respective cliques; she was head of the girls' gang and I was head of the boys'. Or at least that's how I remember it. We thought of ourselves as at war, although, as with wars between gangs or mafia families, both sides were under the eye of a higher authority and mutual enemy, so it had to be conducted furtively, according to certain forms of decorum. We posted WANTED posters of each other around the classroom. I remember arriving in class one morning and being told excitedly by one of my men that Phoebe had taped up a poster of me in the hall. I went to inspect it with devil-may-care aplomb, like Robin Hood coolly appraising his likeness posted by the Sheriff of Nottingham. It was only looking at her photo now, decades later, that I realized, too late, that we'd liked each other. But, because of the grade-school taboo against opposite-sex friendship, our crush had to express itself, tragically, as enmity.

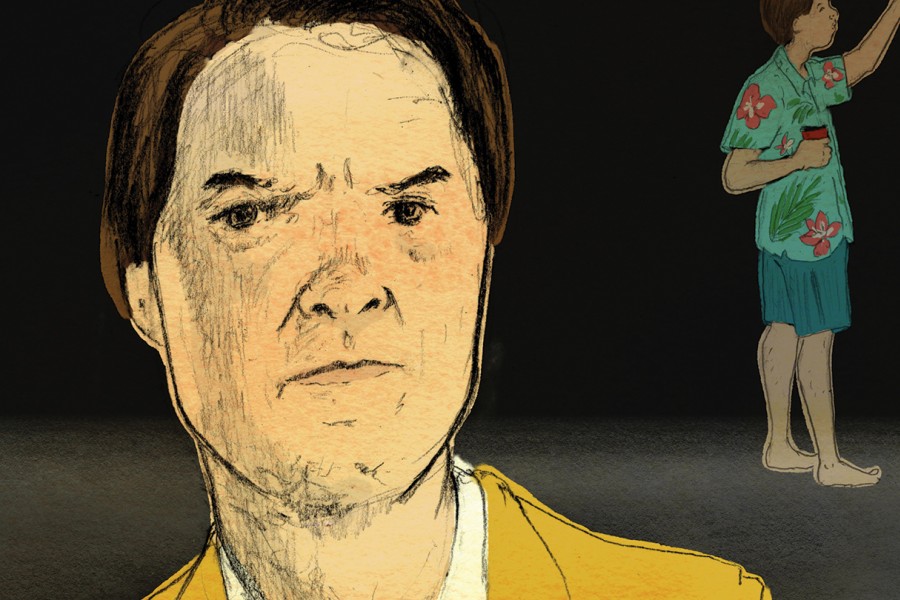

Even now, I can't quite see her as an innocent. That girl was a fifth of trouble poured into a shot glass. You'd see it, too, if you could look at this photo—the arrogant cock of her head, chin up, the bemused crook and arch of her eyebrows, the insouciant double-dare-ya smirk. She's wearing an all-red vest/pants ensemble over black—a pretty put-together outfit for a second-grader. In fact, I'm noticing for the first time that she also has matching red shoelaces. A cunning touch.

I'm also realizing that our faces are right next to each other, mine just over her left shoulder, hovering there like a cartoon devil, smiling out from under my lowered bowl-cut in a manner reminiscent of Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange. Our placement is coincidental—they'd arranged us all by height for class photos—but there seems something fateful about our adjacency, like that photo of Wittgenstein and Hitler standing a couple of kids apart in the same class at Linz. We even look alike; our hair is exactly the same shade of dark brown, our coloration fair, and our smiles are both genuine, albeit evil, instead of the obedient say-cheese grins most of the kids are giving the camera. We could be brother and sister. If you had to pick two kids out of the group as the ringleaders, it wouldn't be hard to identify them.

Looking at this photo now, it occurs to me that it might be fair to say that I am attracted to a certain type—the temptress/nemesis. Around the same time I excavated this photo, I had coffee with another fierce brunette who would make my life hellish if she were my girlfriend, but whom I find hopelessly compelling. In a photo taken of me with another woman, with whom I had my wickedest, most addictive affair, I'm told the two of us look like siblings—fair and dark-haired, with a certain glint in the eye. Phoebe may have been the original of this type, in the same way that some of the other kids in that photo, the first Cheryls, Tonys, or Shellys I ever knew, became the dictionary illustrations of those names in my mind, their faces still flashing in memory for a subliminal instant (Fig. 1: CHERYL) whenever I'm introduced to a new one.

Image credit: Emily Flake

I am not about to look Phoebe up, though I know it's easy to do such things now. It would be not only weird but pointless, like stalking an actress because you're in love with a role she played. I've heard of people who reconnect at reunions with classmates they were infatuated with in high school ("reconnect" being kind of a euphemism here), but I've always been a little suspicious of those romances: Are they really attracted to each other or to the 16-year-olds they remember? Maybe it's just the same sort of Pavlovian nostalgia that triggers a yearning joy when we hear pop songs from our teens, even ones we thought were stupid at the time. There's something depressing about the thought of two vanished adolescents belatedly consummating their desire through the medium of their middle-aged bodies. I have decided it is OK and not creepy that I am still sort of crushed out on Phoebe because it's not the middle-aged me who's crushed out on a 7-year-old girl; it's 7-year- old me, apparently still in there somewhere, and still trouble.

I've encountered the same disconcerting double-exposure effect in real life. At an annual Hanukkah puppet show I attend, which is now the only occasion when I see certain college friends, I saw a gray-haired woman across the room who I at first assumed was someone's mother or co-worker, until I suddenly recognized her as a woman with whom I'd fallen disastrously in love 13 years before. (Yet another alpha brunette.) The instant I recognized her she was again charged with her dark electric aura of erotic danger, the actual woman barely visible behind distorting layers of hurt, bitterness, and desire. Also in attendance was my friend Annie, whom I've known since we were 19. I couldn't tell you what Annie objectively looks like anymore—whether, say, I'd find her attractive if I saw her on the street. It'd be like trying to see letters as abstract shapes again once you've learned to read. All the accumulated memories of her over the decades—the 22-year-old with whom I burgled Kati Jo's shirt back from Zach's dorm room, the 30-year-old with whom I rode the circus train to Mexico City, the 44-year-old who tried out for Jeopardy!—are superimposed over one another, blurring together to form the complex and beloved Annie in my mind. I've known her too long, and love her too well, to see her mere appearance anymore.

I sometimes resent that old friends continue to see me as I was years ago, and not as the person I like to think I've become. Some of them still see the collegiate goofball with an affectation for Hawaiian shirts as my true identity, and the Manhattanite in a Canali overcoat as a pretentious sham. I have to beg Annie not to tell the story again about how I showed up at a chic SoHo restaurant where she was taking me out for my birthday completely blacked out, with a note pinned to my coat asking her to "please excuse Tim's drunkness [sic]," signed by my friends Gabe, Nick, and someone named Bunny—not just because it was a boorish thing to do but because I want to believe, and impress upon everyone, that that story is not about me anymore.

Those obsolescent perceptions feel stifling when you're trying to change while your friends are exerting subtle pressure on you to remain the same, as if they're trying to force you back into one of those Hawaiian shirts or insisting that your favorite song is still "Our Lips Are Sealed." There's some deep conservatism at work here, a denial of age and change. (Maybe this is why child stars so seldom manage the transition to adult careers; even if they turn out to be perfectly attractive adults, they still seem like grotesque caricatures of their iconic childhood selves, as if disfigured by age.) It's especially infuriating when our families insist on seeing us as children, as though we were still, in middle age, in need of instruction in matters like ordering in restaurants or stopping at stop signs. Which is why lots of people instantly revert to surly teens around their parents. You see people react with insanely disproportionate resentment at seemingly innocuous remarks made by siblings or spouses; they're really reacting to the million previous remarks that all insinuated exactly the same thing. It took my mother decades to suppress the reflex to fling a protective arm across me whenever I'm in the passenger seat of a car and she has to brake, as if I were someone whose trajectory she could still hope to interrupt. Our long-vanished selves live on in each other's memories, like Ralph and Alice Kramden still slugging it out, "—to the moon!" and beyond, long after Jackie Gleason and Audrey Meadows have been buried, in thinning signals now spreading out past Capella toward Aldebaran.

We even see ourselves at a delay. It's hard to know what you really look like in the mirror because your 35-, 24-, and 11-year-old selves keep getting in the way. When I was recently persuaded to attempt yoga, I assumed I could still easily sit in the full lotus position, because the last time I tried it, when I was 9, it was easy. I was similarly surprised, when I played a game of ultimate Frisbee, that I had to suddenly sit down and put my head between my knees with a coppery taste in my mouth. A friend of mine once interviewed an artist who'd drawn portraits of women on a Caribbean island known for the freakish longevity of its inhabitants, who told her that even women who were 118 years old, on seeing her drawings of them, invariably said: "I think you drew me looking a little older." I know how they feel, every time I look into a mirror.

Everyone knows that movies don't move; they're rapid successions of still photos flashed before us in the dark. Each frame lingers on the retina for an instant, so that the one we've just seen, now vanished, melds into the next, eliding the darkness between. It is only this brief afterimage that creates the illusion of continuity. Persistence of vision is the name of the phenomenon. The physicist Julian Barbour proposes a theory of the universe in which time does not exist: In his model, the universe is an eternal, changeless artifact frozen in space-time, and time is only an artifact of human consciousness. I do not pretend to understand this theory, but it gives me the metaphysical willies. It threatens to negate not just time but any notion of identity. It's only memory, our own and others', that does for us what persistence of vision does for film—filling in the gaps, bridging the darkness, imbuing our flickering insubstantial selves with character and narrative. We rely on each other's perceptions of us—reductive, outdated, and insulting as they sometimes are—to remind us who we are. Even at those times when we feel more like a stuttering succession of random impulses, they still see us as our same old selves, well-known and as predictable as Little John, Wimpy, or Kramer. Which is why spending time with old friends feels so comfortable, like lounging around the house wearing your rattiest old clothes all day. Their familiarity is a kind of external pressure that helps us retain our shape, countering the internal pressure not only to grow but to go astray or dissolve, to forget our true selves. "Someone needs to know us better than we know ourselves," Richard Russo writes in the novel Straight Man. "We need them to say, 'I know you, Al. You're not the kind of man who....'"

That same stubborn resistance persists through life's last and most unacceptable change. I wonder whether the belief in immortality comes less from fear than incomprehension—we just aren't equipped to understand how something as complex, animate, and formidable as a human personality can simply disappear. There's some truth in the funerary cliché that people "live on in our memories," one more literal and unsettling than that glib consolation suggests. They live on in our heads because that's where they've always lived. We go on considering their wishes, fearing their disapproval, doing things just to annoy them for years after they're gone. It's no different, really, from mourning the snuggly toddlers your standoffish teens used to be, or having a love/hate relationship with a 7-year-old girl who lives in 1974. We never lose our imaginary friends.

I never contacted Phoebe, but just this morning I forwarded a review of a new Led Zeppelin biography to a dead friend. He was a huge Zeppelin fan: He'd always bring along the DVD of the documentary The Song Remains the Same whenever he came to visit me, and crank up Led Zeppelin IV on vinyl when I was trying to go to sleep. At his funeral we got the organist (a ringer we'd recommended) to segue from the recessional, "Danny Boy," into "Kashmir" as his casket was borne from the church. Men wept. I would've forwarded him the article if he'd still been alive, and I saw no reason not to do so now. I gave it the subject heading: "Tirelessly Rocking for Women's Rights," an old in-joke between us. Can something still be called an in-joke if there's no one else left to get it? It's like a tin can tied to a string whose other end is attached to nothing, a song sent into a thousand-light-year void. I pasted in the link to the article, wrote, "Thinking of you," and hit SEND. It never bounced back, so presumably it went somewhere—like the smoke from "hell money" the Chinese burn for their ancestors, or the Bach and Chuck Berry we put on the Voyager probes, bound for the abyss between stars.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged personal essay, memory