The proofreader's mark "stet" means "let it stand," typically meaning that a previous editing mark should be ignored and the copy should read as is. Dora Malech, an assistant professor in the Writing Seminars, cheekily uses this obelus as the title of her new poetry collection, a wry comment on the unusual phrasings, syntax, grammar, and forms found therein. Stet's 38 poems are built around combinations of anagrams, redactions, and constraints, such as making a new poem only out of an anagram of the Sylvia Plath's nine-line "Metaphors." The magazine spoke with Malech to talk about experimenting with form and language, working with young writers, and how language shapes what we know and how we feel.

What drew you to pursue such experimentations as the anagrammatic organizations, constrained forms and language, and remixing of literary allusion? I ask not because I think such experimentation isn't in your previous collections—the emotive and narrative power of musical wordplay runs through nearly every poem I've read of yours—but in Stet you've embraced a more daring degree of difficulty, like a skateboarder who isn't content to level up a conventional trick but wants to try doing it while blindfolded and wearing flip-flops.

You're absolutely right that musical wordplay has always been a driving force for me—both through traditional prosody and through the full spectrum of what Alfred Corn calls "phonic echo." Kay Ryan has called her "snipping up" and "redistributing" elements of sound throughout her poems "recombinant rhyme," which I love for its fanciful implications of poem-as-organism. My experimentations in this book push those elements into more extreme territory; I have a background in visual art, and I was interested in creating a kind of limited palette with my language. When I first began experimenting in this way, it was a very private and intuitive impulse. James Merrill has playful anagramming in his notebooks as well, and I didn't know if mine would go much beyond that. At a certain point, however, I started to see the practice as a heuristic process—applying pressure on the building blocks of my written language to yield the unexpected. These practices became a kind of lifeline for me across changes in my life, my relationships, my location, my body, and my perspectives. I wrote through and into these changes, letting the process that had begun in form become a figure for other kinds of lived making and remaking. Thinking about the recombinant in terms of both sounds and letters enabled me to think on the levels of the verbal, the vocal and oral, and the visual—with Joyce's "verbivocovisual" in mind—simultaneously.

I've been reading your blog posts for the Kenyon Review, where over the past few years you've explored some of the poets or movements you allude to or quote in Stet: Terrence Hayes, Oulipo and Harryette Mullen, James Merrill, Unica Zürn. So I'm curious: What comes first for you—your own analysis of innovative poetry or your own writing experiments? Or does the study and the writing coil around each other as part of the overall process?

Image caption: Dora Malech

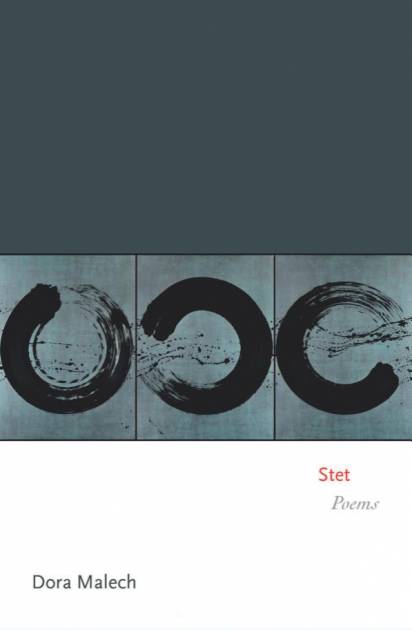

"Coil around each other" is a good way to put it. The cover of my book is a painting by Fabienne Verdier called "Polyphonie": three large-scale brushstroke circles. I felt a kindred energy with Stet in this painting, with its title pointing toward a music of simultaneity and multiplicity while its shapes enact repetition (and difference). It also seems to reference poetry itself, and language (through its lack thereof), echoing Shisui's "death poem"—his single "wordless" circle. That circularity is quite reflective of my process. Sometimes I'll write intuitively and then go looking for others who have shared my formal or thematic impulses. Other times I'll come across a particular move or a particular practice or idea and write toward it, letting that experiment lead me back out into analysis again. This back-and-forth is like creative breath—the taking in and letting out, the same but changed. I'm drawn to other writers and artists who attempt to bridge or reconcile or wrestle with what some still take to be inherent divisions: the linguistic and the visual, the formal and the experimental, the personal and the political, and so on.

For you, how does language shape and inform our intellectual and emotional capacities? I know that's a vague question, but what I find rewarding about experimental writing, be it novels or poetry, is how it makes possible things I didn't previously consider at all.

I agree that all language shapes and informs our capacities, often for the worse. Much of the language we encounter asks us to swallow its message whole or to buy what it's selling. It demands our consumption, not our participation. The language of poetry, particularly poetry that disrupts our linguistic norms, invites participation in the making of meaning. Poetry asks a lot of a reader, but so do our most fulfilling and enduring personal relationships. I am asking the reader of Stet to have a relationship with language. My primary concern as I went deeper and deeper into this project was my own articulation of the emotional stakes. Paradoxically, the practices of constraint—anagramming and redaction—that can seem purely cerebral were, for me, a way to feel my way into my own raw, personal uncertainties. Through poems like "Q & A" and "Essay as yes," I make these concerns explicit, interrogating my own practices in ways that I hope will include the reader. In poems like "do[or]," I insistently redact the word "or" throughout in a way that dissolves and corrodes language to its breaking point. In a book that deals with choices made and then reconsidered, that little coordinating conjunction carried great weight for me, and I wanted the reader to experience that in a nearly physical way.

The older I get, the more I feel like there's always some political component to experimentation in the arts. I think artists experiment because they're trying to come to grips with the world in which they live. It's never simply an intellectual impulse. And from the very first poem in Stet, "Essay as yes," on, there are a few instance—"Q & A," "I Do," "Road Not End," the beautiful "[See: Erosion]"—where I sense a political enterprise as much as a poetic one. For you, are the experiments you're exploring here part of a larger project?

The short answer is yes. I'm trying to articulate my embodied present "in-formed" by both contemporaries and forbears. I'm thinking of the legacy of ideas of l'écriture féminine, of the "French feminist" thinking of Hélène Cixous and Julia Kristeva, of what it means for a woman to write herself into being. I'm also thinking of all that I've learned from the writing and thinking of poets like Evie Shockley and Harryette Mullen, African-American women illuminating formal innovation as response to or reflection of historical, political, social, and cultural contexts. I have been grateful for the opportunity to highlight and celebrate the voices of writers who matter to me and my own work and thinking through my writing for The Kenyon Review, and it seems particularly necessary, of course, to acknowledge the work of women and writers of color in shaping our poetic discourse, since this work is historically undervalued. I'm thinking of the very real and catastrophic ecological implications of our inability to "start over"—that our only option is to work with what we've made and unmade here on this planet. So yes, I see in terms of larger projects—both personally and collectively.

Has working with student writers through your community-based learning courses and working with writers in Baltimore Schools influenced your own work? How?

Working with young writers reminds me to believe that writing really does matter—as empowerment, as discovery, as action, as release. I am inspired by their nerve and bravery and ambition and uncertainty. I am impressed by their willingness to share their work and seek feedback early in the creative process, practices that more experienced writers, ironically, seem to avoid. I appreciate their fresh perspectives on poems. I love listening in on how young people use language, since they're always one step ahead in that regard. In Baltimore in particular, many of the young people with whom I work also have important perspectives on inequality and power, and I am both grateful for the opportunity to see our city through their eyes and frustrated by much of what I see.

Tell me a bit about the poets and pieces of writing you use as source materials or thematic signposts in a few poems—Sylvia Plath, Meg Ronan, John Keats' epitaph "Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water," historian Samuel Kinser. I think experimental film and experimental poetry overlap in terms of their approach to language, I think poets think about quotation, the writers or poets they namecheck or use, more like hip-hop DJs, where samples are as much about personal style, taste, and interests as they are filling a specific musical purpose.

I said that Verdier's "Polyphonie," my cover image, had a kind of kindred energy, and the same goes for those named above. Kindred energy and shared obsessions. Some, like Plath or Ronan, have a similar interest in constrained form (the lines of Plath's "Metaphors" are syllabic; Ronan uses the Oulipian belle absente form) while also writing "about" similar themes in the poems I reference—a pregnancy, a wedding. Others, like Andrew Joron or Nathaniel Mackey, endlessly excite and inspire me in their use of sound. You might notice that the dedication at the beginning of the book is "redacted" in brackets. There is a sense in this book that I'm writing across transitions; pronouns are destabilized across the collection as I change and my relationships with others change. Across those personal changes, the sense of solace and companionship I felt in the company of the poetry and scholarship of others remained a constant, and I wanted to celebrate those voices—some friends, some strangers, some long dead—by naming their names.

Where has Stet taken you? Where do you see your own work going from here?

While I was writing Stet, I was also writing poems outside of the parameters of its particular formal project (though still engaged with formal elements), and that other manuscript, Flourish, should be published in the next few years. Having an outlet for the dense and concentrated linguistic energy of Stet enabled me to put a different energy into writing poems for Flourish that were more narrative and imagistic. I don't want to choose between modes; I want to widen and deepen both my formal practices and my concerns as much as possible. Stet also opened some doors for me in my visual art practices. For years, I have been engaged in a kind of repetitive, obsessive drawing and painting practice completely separate from my writing. When I began to tap into the constrained alphabetic re-workings of Stet, I realized that I had found a writing practice in conversation with my visual practice and started to bring the two together on the same page. Some of these "visual poems" appeared in the May 2018 issue of Poetry magazine, and I'm excited to keep transgressing those boundaries. I'd also like to further articulate some of the connections and patterns and innovations that shaped my thinking about Stet and contemporary poetry through my critical prose.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged writing seminars, poetry, q+a