Westerners have been mistreating Egyptian mummies for centuries. European apothecaries sold powdered mummy as a medicine as late as the 20th century. For hundreds of years, artists painted with "mummy brown," a pigment made of ground-up mummy. Victorian aristocrats collected them, in some cases unwrapping them as a public spectacle. In 1833, a prominent French monk remarked that "it would be hardly respectable, on one's return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other."

We're no longer so cavalier with the bodies of ancient Egyptians. But the designers of a new exhibition at the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum argue that even now, we often do not treat them with the respect we accord other dead bodies. "Almost the first thing people say when they come across a mummy in a museum space is, Is it real?" says Meg Swaney, a doctoral student in the Department of Near Eastern Studies who helped shape the exhibition. Swaney wrote her master's thesis about the ethics of displaying Egyptian mummies. She says the long history of treating them as commodities, coupled with their frequent appearance in horror films, has affected how we think about them. "There's some sort of disconnect between coming to a museum space and seeing a dead body and not recognizing it [as a human being]."

The new exhibition, Who Am I? Remembering the Dead Through Facial Reconstruction, aims to breathe some humanity back into the bodies of two mummified women. They are known as the Goucher Mummy and the Cohen Mummy, after their respective Baltimore collectors: Methodist minister John Goucher and Colonel Mendes Israel Cohen. But the show largely sidesteps the collectors. Instead, as much as possible, it presents the mummies as once-living individuals.

Image caption: John Goucher (far right) is photographed with a group of American Methodist missionary observers in Egypt. The photo is dated 15 November 1906, near the Giza Pyramids.

Image credit: Rev. John Franklin Goucher Papers

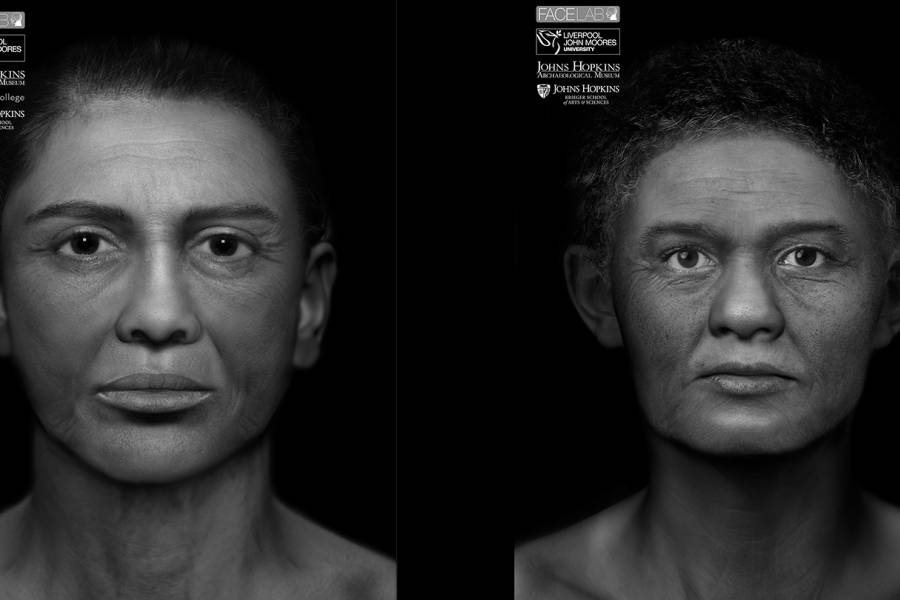

The most striking element in the exhibition is a pair of images: digital headshots of what each of the women may have looked like in life. The faces are compelling and deeply human; they would not look out of place browsing in the campus bookstore. Funded by a Johns Hopkins Arts Innovation Grant, an interdisciplinary team of museum professionals, forensic experts, Egyptologists, osteologists, radiologists, plastic surgeons, and students spent two years resurrecting the faces of these women as well as elements of their biographies using their remains as a guide. It was a monumental challenge: The person now known as the Goucher Mummy lived 2,400 years ago. The Cohen Mummy is at least 200 years older.

Like many mummies, these two have a checkered past. John Goucher purchased one of the mummies in Egypt in 1895 for display at a school he co-founded, the Woman's College of Baltimore City (later renamed Goucher College). The mummy's coffin was lost shortly after, around the same time Goucher made an initial attempt to unwrap her. As recently as a decade ago, the body was still shedding bits of wrapping and resinous materials. At the time, Sanchita Balachandran, now associate director of the museum, a senior lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies, and a driving force in the design of the new exhibition, was charged with conserving the mummy in preparation for a museum renovation. She spent three weeks reassembling the linen and carefully preparing the body for transport—weeks spent bent over the desiccated skin, the high cheekbones, the slender hands. "Having worked with her so closely, it's impossible to disregard her humanity," Balachandran says. "You're there with this individual, and you have this very keen sense that this is a person."

The Cohen Mummy, identified as "a youth" in Colonel Cohen's records, was in even poorer condition. Cohen was a prominent Baltimorean who as a young man helped defend Fort McHenry against the British. He traveled to Egypt in 1832 to purchase hundreds of antiquities, including the mummy. After his death, the mummy was donated to Hopkins. In 1979 it was disassembled for an autopsy, during which the body was identified as that of a boy. In the intervening years, some parts of the body were lost. (In the exhibition, only the mummy's coffin is displayed.) But with the pieces that remain, the museum team determined that the Cohen Mummy was, in fact, an adult woman. It was one of many surprises over the course of the project.

The process began in 2016, with a CT scan. The team carefully transported the mummies to Johns Hopkins Hospital, where they uncrated them and placed them in the scanner, which had to be reset for the mummies to get useful results. "The CT specialists were blown away," Balachandran says. "They were excited to pump up their machine to radiation levels you can't use on living people."

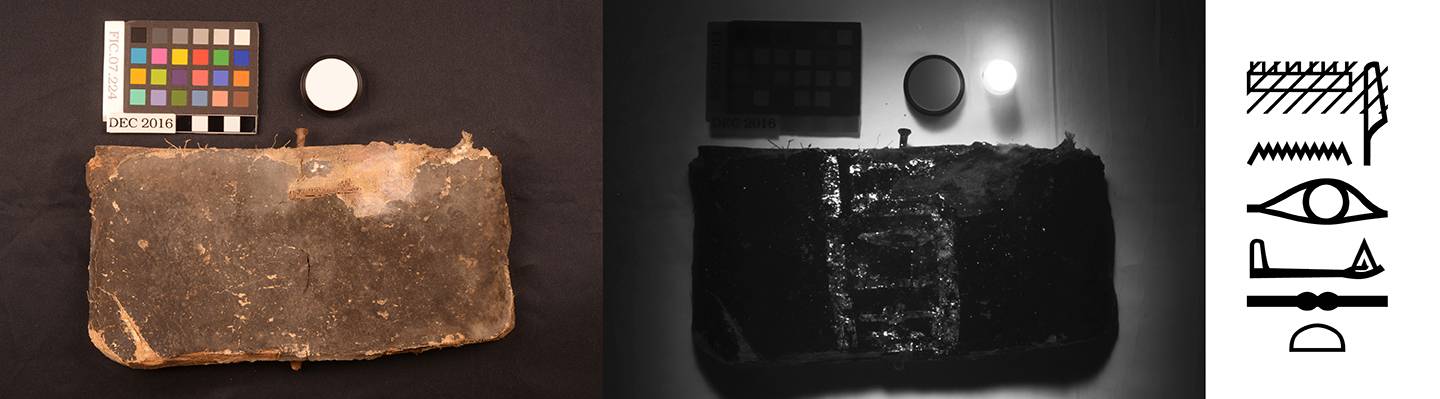

Image caption: The Cohen Mummy's coffin may have revealed the mummified woman's name, visible under infrared light

Image credit: The Johns Hopkins Archaeology Museum

The team then sent the CT data to a research group in Liverpool, England, led by forensic anthropologist Caroline Wilkinson. Wilkinson and her team at Face Lab create 3-D depictions of deceased individuals using skulls and a host of archaeological, historical, and forensic data. They are best known for re-creating the faces of historical figures including Richard III, the poet Robert Burns, and St. Nicholas. Using a virtual sculpture system, Face Lab assessed the mummies' skull structures and added major facial muscles accordingly. They estimated the average depths of soft tissue, taking into account the likely diet and lifestyle of an ancient Egyptian. The skulls even provided clues about the shape of the nose. (Skeptical? Blind tests using living people have found such reconstructions to be surprisingly accurate.)

Next, a facial prosthetics expert at the School of Medicine helped the team scan the mummies' faces with lasers. That provided information on surface details like skin and hair. Osteologists helped determine the likely age of each of the women, which led the team to add wrinkles. The team blurred areas they were less certain about, like the hair, and used some informed guess-work in areas like the Cohen Mummy's lower jaw, which is missing.

Along the way, partial biographies of the two women took shape. The Goucher Mummy likely lived to be 45–50 years old and bore at least two children. Her teeth were in good shape, though very worn. (That was typical for ancient Egyptians; their food was often contaminated with sand.) For unknown reasons, she had unusually strong jaw muscles. The mummies appear to have had both sub-Saharan and Caucasian features, suggesting a mixed ancestry, common for Egyptians of the time. Less is known about the Cohen Mummy because her body is only partially intact. She was short, even for the era: about 4 feet 7 inches tall. She probably lived to middle age and may have had children. She suffered from painful tooth abscesses. And she may have been named after the Egyptian god Amun.

That last revelation came one afternoon when Balachandran was alone in the lab working on the coffin. The ancient Egyptians used a pigment called Egyptian blue, which under certain conditions emits infrared radiation. A camera modified to see in the infrared range can capture images painted with the pigment that are invisible to the naked eye. Balachandran was examining the Cohen Mummy's coffin using one of these modified cameras. Age had entirely blackened the footpiece. "I looked at the footpiece and thought there's going to be nothing here," she says. "But it's small enough to move so I thought I might as well get it done." Balachandran was taking photos when suddenly a cluster of hieroglyphs appeared. "I thought, 'Oh my God!'" The Egyptologists on the project concluded that the hieroglyphs spelled out a name: Amenerdis, which means "it is (the god) Amun who has given her." If the coffin originally belonged to the body within, Balachandran has resurrected another fragment of her identity. "I hope that's her name," Balachandran says. "Having a name is very satisfying to me. I feel like we were able to bring back some parts of her from all of this dismemberment."

Throughout the project, the team has remained focused on that goal: rescuing these two human beings from obscurity. Their respectful stance has at times kept them from learning as much as they might. They have not, for instance, extracted any DNA from the bodies. "This is the question at every stage," Balachandran says. "If you do an intervention, what do you gain from that? And what do you potentially lose in terms of one's integrity and encroaching on the dignity of these individuals?"

No statutes govern the treatment of Egyptian mummies, unlike, say, the remains of Native Americans. So the team sought guidance from the International Council of Museums. The organization's code of ethics states that all human remains should be treated in a manner consistent with the beliefs of the community from which the remains originated. That meant thinking about how ancient Egyptians would have wanted their dead to be treated. Fortunately, the ancients left instructions about the afterlife on papyrus scrolls. For them, the body and the soul were not separate entities. Mummification preserved the body, but the memory of the individual also had to be preserved. And the Egyptians accomplished that largely through pictures.

"They believed the spirit of their dead could inhabit an image on the wall," Swaney says. In that sense, the reconstructed digital portraits of the mummies seem uniquely appropriate. We will never know whether the spirits of the Goucher Mummy and Amenerdis reside in the captivating renderings that hang on the Archaeological Museum walls. But visitors to the exhibition are not likely to ever again see mummies as lifeless artifacts.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Science+Technology

Tagged archaeology, archaeological museum