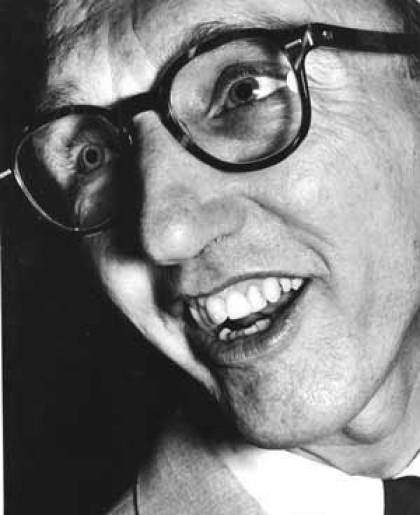

Image credit: Stephen Eric Thomas

The predecessors of Cordwainer Smith first appeared in a teenager's notebook, the title UNBORN DEVILS scrawled across its cover. Eight names were listed, along with biographical sketches detailing where they grew up and went to school. Each had a chosen genre and was assigned a pseudonym. Isidor Guldheimer wrote as Anthony Conquest. Luci d'Este preferred Anthony d'Este, though both were pseudonyms because his/her "real" name was Gerald Pinkson. Then there was the euphoniously named J.W. Doublewood, and Karloman Jungahr.

The notebook belonged to Paul Linebarger, who under his own name played many roles: U.S. Army colonel, CIA operative, psychological warfare expert, scholar of Asia, teacher, adviser to an American president. He was a husband twice and a father twice. His godfather was the first president of modern China, Sun Yat-sen. He may have been the central unhinged character in a famous psychiatric case study. But it was his science fiction—published as Cordwainer Smith—that gilds his legacy today.

Image caption: Cordwainer Smith

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

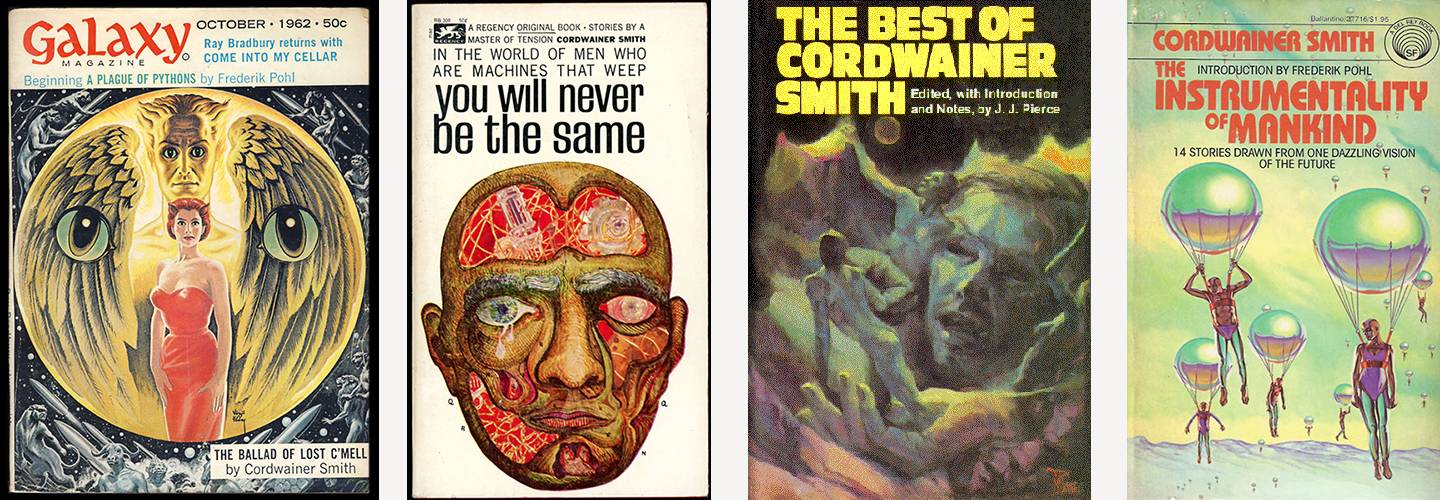

Smith published about 30 short stories, all of which take place over a 14,000-year future history that Linebarger labored over in a lifetime of notebooks. Smith's work is startling and violent, remembered for its originality and its weighty subject matter. In a letter to his agent, Linebarger explained that his stories "intended to lay bare the human mind, to throw torches over the underground lakes of the human soul, to show the chambers wherein the ageless dramas of self-respect, God, courage, sex, love, hope, envy, decency, and power go on forever." Pulpy tales of little green men these were not.

For the 15 years that Cordwainer Smith was publishing his remarkable science fiction, few readers knew the writer was actually Paul Linebarger. Today, it's hard to nail down just who Paul Linebarger really was. At first pass, his life appears to be a bizarre amalgamation of identities, unrelated achievements, and perhaps, if the rumors are true, even psychoses. Linebarger himself addressed his splintered identity in that childhood notebook: "I myself now half-believe in the dim individualities of these pseudo-literary sub-souls of mine."

But a closer look reveals something more extraordinary than his collection of identities, both professional and literary. It seems Linebarger's many sub-souls collaborated in a kind of unified intention, working together in a battle against complacency and capitulation to malevolent powers, both global and personal.

Lin Bah Loh, Forest of Incandescent Bliss

Linebarger's father, Paul Myron Wentworth Linebarger, led the globe-trotting, serice-minded life his son would emulate. Linebarger Sr., son of a minister, was sent to Europe at age 16. He studied at Heidelberg University and earned his law degree from the University of Madrid before serving as a cavalry lieutenant in the Spanish-American War. It was his highly specialized knowledge of Spanish law that earned him an appointment as one of the first U.S. judges in the Philippines, a newly seized American colony at the time. There he met Sun Yat-sen, a young revolutionary seeking funds and support from Chinese expatriates to overthrow the Qing dynasty. While the details of this meeting are largely unknown, it would be a radical turning point in the judge's life. In 1907, Linebarger Sr. resigned his judicial post to become Sun's legal adviser and financial backer. He would be responsible for some of Nationalist China's most-circulated propaganda.

In June 1913, the judge sent his pregnant wife, Lillian Bearden Linebarger, from their home in the Philippines to Milwaukee so that their child would be a natural-born American citizen and therefore eligible one day for the U.S. presidency. When his mother brought him back to China, he was christened Lin Bah Loh, or Forest of Incandescent Bliss, the godson of future President Sun Yat-sen.

During the younger Linebarger's early years, his family's livelihood and location were largely dictated by the turbulent status of Sun's political ambitions. At times of civil unrest in China, Linebarger, already a sickly child, would be sent away, as he was in 1919, to a boarding school in Hawaii. While tussling with a classmate there, he suffered a catastrophic injury to his eyes. He lost one; some texts say it was damaged with a wire, others say a tree branch. He wore a glass prosthetic, and doctors were able to save the other eye, though it would eventually be damaged by infection. His near-blindness was an addendum to a long list of Linebarger's maladies, which eventually included crippling digestive and metabolic disorders.

The family spent time all over Asia and Europe, as well as the American South, never settling anywhere for more than a year. Linebarger attended more than 30 schools. Though his life seemed glamorous from the outside, the instability and social isolation were difficult for him, and the boy found solace in books, becoming enamored of fantasy and science fiction novels. His love of reading quickly turned into his own literary experimentation and notebooks full of literary personas. Writing ran in the family. The judge, in addition to books he authored about the struggle in China, wrote poetry, fiction, and drama—under a pen name, naturally.

At age 15, Linebarger published his first short story, "War No. 81-Q," while in school in China, under the pseudonym Anthony Bearden. (Later Linebarger would recycle this pen name to publish poetry.) By his early 20s, he was back in the States and enrolled at Johns Hopkins as a doctoral candidate in political science.

In his memoir, From Loss to Renewal: A Tale of Life Experience at Ninety, classmate Chu Djang remembered Linebarger as a "quick-witted" and "brilliant student." According to Djang, Linebarger drove the 45 miles from his home in Washington to Johns Hopkins every morning while simultaneously reading the day's newspaper—a perilous endeavor for anyone, let alone a man with one eye.

Already well-traveled and fluent in six languages by age 23, Linebarger was awarded his doctorate. Not long after, he was recruited by U.S. Army intelligence.

Paul Linebarger, anti-communist

Linebarger began his academic career in 1937 at Duke, first as an instructor and later as an assistant professor. During this time he married, had two daughters, and published multiple scholarly books on East Asia. He also continued to deal with illness, both physical—Arthur Burns, a close friend of Linebarger's, remembers him drinking a diluted solution of hydrochloric acid at a dinner party to ease his stomach pain—and emotional. Linebarger was placed under an informal suicide watch by his psychologist after the dissolution of his first marriage. He also continued his work with the military, eventually earning a reserve commission; he would later serve on active duty. Soon, he had become one of the country's foremost experts in psychological warfare, using his expertise to pick up his father's mantle in the fight against communism.

In communism, Linebarger saw more than an economic or military threat. He saw the ideology as the antithesis of self-determination, a creed that rejected not only freedom of choice but also the role of individual struggle as central to one's humanity. And he felt that propaganda and psychological warfare were central to the ideology, calling communism "permanent psychological warfare in action." Linebarger believed the communists wielded propaganda tools with such skill that he attributed an almost supernatural effectiveness to them. (He once observed that passive Vietnamese farmers transformed into "leopards once they read Marx, Lenin, Mao Tse-tung, and Ho Chi Minh.")

Linebarger recognized the United States' disadvantage in the propaganda battle against the communists. Not only did the transparency of the American government limit clandestine efforts against our enemies, but our political system, lacking a unified politburo or single personality driving our foreign policy, made it difficult to deliver believable long-term threats or promises that could be used in propaganda efforts. Linebarger called the United States the "first immense human community that survives without profound dogma or profound hatred ... [attempting] to make short-range, practical, and warm-hearted (though ideologically superficial) concurrence the foundation for a political and industrial civilization." Without dogma or class hatred to draw on, American propagandists were at a disadvantage compared to their communist opponents, he believed.

The United States could not afford to cede the propaganda battlefield to the communists. As a young man, Linebarger had seen the results of such a loss when, despite his father's and godfather's best efforts, the Communist Party of China continued to gain support. In his contemporary writings on the Chinese civil war, Linebarger consistently cited communist propaganda victories as the primary impetus for the Nationalists' demise. It was communist propaganda that promised agrarian reform, buttressing the party's ranks with hundreds of thousands of landless peasants. It was pamphlets and radio broadcasts that transformed communist guerrilla victories against the Japanese into patriotic triumphs. It was the potent communist propaganda—what Linebarger called "strong, black magic"—and the inability of the Nationalists to respond that, he believed, was ultimately responsible for China's 25-year civil war and the estimated 2.5 to 7 million deaths it wrought. He was determined to prevent it from happening again.

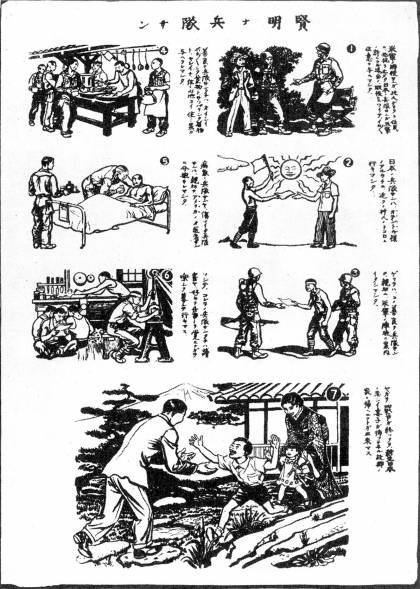

Image caption: From Psychological Warfare, this illustration was carefully adapted to Japanese customs and depicted how surrender leads the Japanese soldier back to his wife and children.

Image credit: Project Gutenberg

During World War II, Linebarger was stationed in India and China, serving as a linguist, propagandist, and liaison between Chinese and U.S. intelligence. By the end of the conflict, Linebarger had been promoted to major and became a self-proclaimed "visitor to small wars." The chaos after the collapse of the Japanese Empire left East Asia vulnerable to the intervention of communist regimes. During the late 1940s, Linebarger traveled the region, attending to one communist insurgency after the next; in Malaysia he ran psychological warfare operations in support of the British forces fighting Chinese-led communist guerrillas; he also advised anti-communist efforts in Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. He often returned to China during this time in an ultimately vain attempt to reverse the fortunes of the Chinese Nationalists as they made their slow retreat across China, eventually leaving the mainland under complete control of the communists.

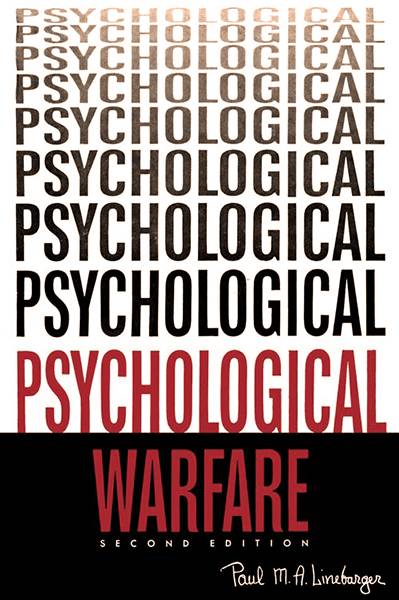

Linebarger did not limit his assistance to strategic planning or advising military officers from the safety of a garrison. He didn't demur when circumstances called for him to put himself in danger, whether tossing pamphlets from low-flying airplanes or collecting intelligence from unsuspecting foreign officials. Between overseas missions, he moved from Duke to the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and completed his most famous non–science fiction work, Psychological Warfare, which was published in 1948 and is still referenced by Western military training manuals.

From 1950 to 1952, Linebarger deployed to Korea, where, according to science fiction publisher J.J. Pierce, he pulled off a memorable coup. Late in the conflict, when Chinese soldiers began to surrender, they were approaching American troops with weapons still in hand because dropping them was too dishonorable. American soldiers, believing they were still under attack, were firing upon and killing the surrendering Chinese. Linebarger met with Chinese prisoners to devise a series of Chinese words a soldier could yell when he wished to surrender—culturally acceptable words like love, virtue, and humanity that did not insult the soldier's honor but when said together were phonetically similar to the English words, "I surrender." Pamphlets with explicit surrender instructions were dropped behind enemy lines and the number of botched surrender attempts decreased significantly. According to his widow, Linebarger considered saving the lives of these surrendering Chinese soldiers his most worthwhile accomplishment.

Image credit: Project Gutenberg

After Korea, Linebarger returned to his position as assistant professor at SAIS. In a memoir titled China Watcher, China scholar Eugene Levich, SAIS '62 (MA), recalls that on the first day of the semester, Linebarger was known to end class with a maxim: "The essence of psychological warfare is shock and surprise." To illustrate his point, the professor then "took the glass eye out of its socket, flipped it up in the air, put it into his pocket and exited the classroom."

Levich remembers Linebarger as "enormously open-minded, kind to everyone, even to people of whom he disapproved politically." Linebarger testified on behalf of colleague Owen Lattimore when he was subpoenaed by Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who alleged that Lattimore was a high-level Soviet spy working in the U.S. Despite their political differences—Linebarger's conservative sentiments were well-known, Lattimore was an open admirer of Stalin—Linebarger defended his friend and took over his classes during the hearings.

Linebarger's academic activity provided a convenient cover for his continued work in psychological warfare. In his book Portrait of a Cold Warrior, former CIA operative Joseph Burkholder Smith described a seminar for CIA operatives that Linebarger taught at his Washington home: "Going to Paul Linebarger's house on Friday evenings was not only an educational experience ... it was also an exercise in clandestinity. Each seminar was limited to no more than eight students. They [the CIA operatives] were told to pose as students from the School of Advanced International Studies, to go to Paul's via different routes, and to say they were attending a seminar on Asian politics."

During this time, Linebarger was juggling his various roles—CIA expert, scholar, teacher—as well as coming into his own as sci-fi visionary Cordwainer Smith. But his all-consuming battle with communism would bleed into his art. In Atomsk, a now out-of-print novel published under the pseudonym Carmichael Smith, Linebarger dedicated the book "to the Russian people, who are great and will one day be free."

Cordwainer Smith

In a life hectic with travel, scholarship, and family, somehow Linebarger found time to write science fiction, often when he was too sick to work. His friend Arthur Burns remembered that "he was confined to bed a great deal, and he'd often write these stories when he couldn't get up and lecture. He was a man who wrote naturally and very easily. He'd sit at his typewriter and just knock it out. I've never seen anyone compose so fast when he had it on him."

By 1950, Linebarger had published two mainstream novels under the name Felix C. Forrest, a pseudonym that played on his given Chinese name. When fans of his work discovered the author's identity, Linebarger found himself unable to write anything else under that pen name, dismayed by the attention and the pressure of an audience. When he turned his attention back to science fiction, Linebarger became Cordwainer Smith, a pseudonym imbued with connotations of creation: A cordwainer makes leather shoes, a smith shapes metal.

Cordwainer Smith's first published short story, "Scanners Live in Vain," was written in 1945 and rejected by just about every publication in the genre. Editors felt the story was "too extreme," a pointed rebuke in a genre not known for subtlety. "Scanners" finally saw the light of day in an obscure magazine called Fantasy Book, a semiprofessional magazine that put out only eight issues between 1947 and 1951. In a stroke of luck, Linebarger's story appeared alongside one by esteemed science fiction editor and writer Frederik Pohl. A year later, when Pohl was assembling his widely read anthology Beyond the End of Time, he remembered and included Smith's work, thus delivering "Scanners" to a wider audience.

"Scanners Live in Vain" is quintessential Smith: a story that has produced interpretations so varied its 34 pages have been construed as a Christian allegory, a manifesto on American individualism, and an edict on the life-affirming power of empathy. Like other stories written under the pseudonym, this one features a brave central character who must act against an unfeeling majority to defend or reclaim an element of humanity that's been lost to technology or bureaucracy or both.

Martel, the story's protagonist, is a scanner, sort of an elite police officer patrolling the outer reaches of the universe. In order to survive the hostile environment, what Smith refers to as "the great pain of space," scanners must undergo a desensitization procedure, sacrificing their hearing, taste, and all feeling so that they can brave the elements and maintain order. It is a lonely life, buoyed only by the tightknit fraternity among the scanners and the infrequent permission to "cranch"—make use of a special device to temporarily restore normal human sensation. When a scientist claims to have found a way to allow normal humans to endure the great pain of outer space, Martel's colleagues decide the man must die, or else their interstellar monopoly will be no more. But Martel, who happens to be cranching and whose temporary empathy makes him immune to the coldly logical groupthink of the scanners, intervenes to save the scientist—and the enormous potential of his discovery—wistfully imagining what it would be like "to feel a decent clean pain." Here Smith's message is manifest: To live a real life—one certain to include physical pain but at least the capacity to feel it—is far superior to a life of numb detachment. Martel becomes a hero when he loses his conditioning and speaks up for what is right.

We see this trope again and again in Smith's work: the singular courage to embrace an authentic, if painful, existence, and to reject the sanctuary of conformity for the mundane and beautiful and awful experience of being alive. But we also see evidence of Linebarger's experience here, too. The scanners who lack sensation recall Linebarger's own visual impairment, and the cold consensus of the scanners to use violence for a greater good echoes the communist ideology that so disturbed him.

"Scanners Live in Vain" represents just one day in the 14,000 years of the future history Linebarger imagined in his stories, notebooks, and manuscripts—similar in scope to Frank Herbert's Dune. Smith's future history, called The Instrumentality of Mankind, is meticulously arranged so that stories don't simply dovetail with each other but sometimes occur simultaneously. Contemporary Algis Budrys marveled that "what appear to be loose ends or, at best, plants, are in fact integral fragments of other parts which will not take on their intended function until he later lays down the main body of that part." The only thing hindering Smith, Budrys said, was being constrained to "describing infinity in finite time."

At the dawn of this epoch (which begins not long after the aforementioned "War No. 81-Q"), the Instrumentality, a kind of omnipotent galactic government, has taken power to end suffering and enforce social harmony. Human lives have been extended tenfold by new drugs. But in its efforts to manufacture a world free from suffering, the Instrumentality has instead reduced existence to a marathon of meaninglessness. Here again we find Linebarger hard at work behind the scenes. This socially engineered utopia recalls the communist repudiation of personal freedom in favor of progress. Characters in these stories enjoy near-immortality but lack the humanity they need to savor it. In Smith's universe, redemption comes from the rekindling of the Old Strong Religion (a nod to Linebarger's Episcopalian faith) and the Rediscovery of Man, in which the inhabitants of the future trade their soulless utopia for the danger, disease—and autonomy—of their ancestors. Their lives will be shorter and more brutal.

Smith's short story "Alpha Ralpha Boulevard" takes place shortly after this return to old ways and begins with the first application of a postage stamp in more than a dozen millennia. "Everywhere," a narrator named Paul tells us, "men and women worked with a wild will to build a more imperfect world." This new world may not be perfect, but it is free. Life may still be full of sickness and pain for people like Paul Linebarger, but it beats anesthesia or, worse, apathy. If these pages crackle with a prescriptive intensity, it's probably because they were meant to. Linebarger once said, "Almost all of the best propagandists of almost all modern powers have been literary personalities."

Kirk Allen?

When psychologist Robert Lindner's case study, "The Jet-Propelled Couch," was published as a 1954 two-part series in Harper's, some readers thought its main character sounded a lot like Paul Linebarger. Lindner (who was already well-known for his book Rebel Without a Cause, which detailed his work with a violent psychopath and was the basis of the 1955 film starring James Dean) begins his story on a summer morning in Baltimore. He receives a phone call from a military physician desperate for his help. The man's patient, "Kirk Allen," is in his 30s and "perfectly normal in every way except for a lot of crazy ideas about living part time in another world." Allen's productivity has been dwindling as the time he admits to traveling in "his interplanetary empire" has increased. The doctor cannot dislodge Allen from this reverie-turned-psychosis and requests Lindner's expertise.

Lindner describes Allen's upbringing as—like Linebarger's—far-flung and isolated. As a boy, Allen feels alienated and apart from other children his age. His father is referred to as "the Commodore," just as Linebarger called his "the Judge." Young Allen turns to fantasy books for company and discovers a protagonist that bears his same name. This experience transforms Allen, who on Lindner's couch explains: "The stories were not only true to the very last detail but they were about me. I knew what I was reading was my biography." Using these books as a launching pad, Allen spends decades filling in the blanks of his biography. Lindner recalls the "maps, charts, diagrams, architectural layouts, genealogical schemes, and timetables" that sound a lot like the notebooks the teenage Linebarger pored over for years.

If Linebarger was indeed Allen, did he go on to channel his imagined world into a catalog of science fiction classics? Was Cordwainer Smith's Instrumentality the expression of these fantasies? Allen's delusion that he was the hero, the lord even, of his own universe, would indeed give greater insight into Paul Linebarger's boundless ambition and personal ideology, as well as Cordwainer Smith's gallant protagonists.

Of course, the consequence of a rumor—especially the stubborn kind—is that, at some point, what's true and what's not stop mattering. In the firmament of the popular imagination, Kirk Allen now exists in the same constellation as Paul Linebarger, for better or worse. While primary source material that examines the life of Paul Linebarger and even the work of Cordwainer Smith remains relatively scarce, the texts that take on the Kirk Allen conundrum are common, and have been penned by everyone from Carl Sagan to comic book magnate Stan Lee.

It's fitting that Linebarger—a man who cultivated so many identities and crafted even more on the page—is forever bound to mystery. Among so many pen names and clandestine operations, Kirk Allen seems to fit right in.

All the sub-souls

It is possible Paul Linebarger's notebook full of literary sub-souls was a response to a lonely childhood on distant islands, a vast collection of friends to keep him company. Maybe they were a cover that ensured his respectability among military and academic colleagues. Perhaps the pseudonyms Linebarger employed were playful, experimental, and carefully chosen elements that were as much a part of each story as the setting. But if he was the real-life Kirk Allen, perhaps Linebarger's alter egos were symptoms of actual psychosis.

Or maybe these characters—together with Linebarger's various professional personas—were not divergent parts of him after all but rather a collective working toward the same end. While stationed in India during World War II, Linebarger wrote to his then infant daughter that he had spent a lifetime "wandering through whole throngs of myself." It now seems clear that there were many Paul Linebargers, all of whom were, despite the persistent illnesses of the world and his own body, relishing each mundane and beautiful and awful moment.

Paul Linebarger died of a heart attack at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1966 after a prolonged illness. He was interred at Arlington next to his second wife and survived by two daughters. His official Arlington biography describes him as a "very private man," as well as a "remarkable writer, thinker, and scholar."

Near the end of his life, Linebarger wrote to a friend: "Life is a miracle and a terror. The progress of every day, any day, in the individual human mind transcends all the wonders of science. It doesn't matter who people are, where they are, when they lived, or what they are doing—the important thing is the explosion of wonder that goes on and on—stopped only by death." For Linebarger, the great pain of space, totalitarian regimes, psychological disturbances, and physical maladies could all be defeated by recognizing the meaning that suffering can lend to our humanity, by mining our own individual and endless capacity for reinvention, curiosity, and awe.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society, Alumni

Tagged alumni, science fiction