As it orbits the sun, our blue planet lives in the line of fire. Small asteroids, between 3 and 20 feet in diameter, hurtle toward Earth almost daily. Most break up harmlessly in the upper atmosphere. Once every millennium or so, however, a sizable object breaks through and hits the surface with enough power to destroy a town or small city. The threat is so serious that NASA last year established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office dedicated to tracking potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroids and comets and figuring out how to protect us from impact. To aid in this effort, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory proposed the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, the first-ever mission to demonstrate how catastrophe could be averted by deflecting an asteroid.

Data

In 1998, NASA launched the Near-Earth Object Survey program to detect, track, catalog, and characterize near-Earth asteroids and comets. Since then, an estimated 93 percent of the near-Earth objects larger than 1 kilometer have been cataloged. The energy released from a rare 1-kilometer asteroid hitting Earth would be equivalent to detonating the world's combined nuclear arsenal all at once, says Andy Cheng, the chief scientist for APL's Space Department, who along with planetary scientist Andy Rivkin co-leads the DART investigation. The NASA program is now focused on finding intermediate-size comets and asteroids ranging from 140 meters to 1 kilometer. A 160-meter asteroid, Cheng says, would pack the punch of a hydrogen bomb.

Alternatives

NASA has considered several asteroid defense strategies. None involved sending a misfit team of drillers led by Bruce Willis to impregnate an asteroid the size of Texas with a nuclear bomb. However, one possible defense is launching a nuclear weapon to deflect or destroy the threat. "But that brings up all sorts of political questions. For one, nuclear tests are illegal," Cheng says.

There's also the gravity tractor technique, which involves a spacecraft that would rendezvous with the near-Earth asteroid and fly alongside it for years. The gravitational tug of the spacecraft, weak though it may be, could still be enough to pull an asteroid away from its collision course. However, gravity tractors might not be effective for asteroids over 500 meters in diameter and would require decades to build and carry out a mission.

The plan

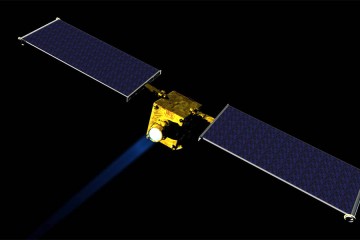

The DART team opted for the kinetic impactor technique—essentially striking an asteroid hard enough to shift its orbit away from Earth. A refrigerator-size spacecraft will be launched toward the target rock, hitting it at a velocity nine times faster than a bullet. In theory, this crash should change the speed of a threatening asteroid by only a centimeter per second, but over several years this nudge should prove sufficient to shove the asteroid onto a new and harmless course. DART's target is an asteroid binary system called Didymos—Greek for "twin"—that will make a distant approach to Earth in October 2022. The spacecraft will collide with the smaller of the two bodies, Didymos B, which at roughly 530 feet long is typical of asteroids that could create regional damage should they crash into Earth. A binary asteroid is the ideal natural laboratory for this test, Cheng adds, because the change in trajectory of the smaller asteroid can be tracked from Earth-based observatories, but the gravitational pull of the larger asteroid will ensure that the pair will still safely orbit the sun and not go hurtling out into space.

Next step

DART recently moved from concept development to the preliminary design phase, following NASA's approval. Managed by APL and overseen by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, the spaceship and associated technology will be completed by December 2020. If all goes as planned, the craft will be launched from Earth as early as March 2021 aboard a commercial satellite, and then travel to impact with Didymos B in October 2022.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory