Shakur Brooks has a bass line looping in his head. The eighth-grade trombonist sits on a metal chair in the band room of the Booker T. Washington Middle School for the Arts in West Baltimore, punching out this line on repeat. It starts on his favorite note, D-flat, and is followed by two more low notes that mark a stalking beat. After school on the last Monday in April, the bass line fills this windowless basement where Brooks sits and blows his trombone, laying down a funky strut for himself, a few classmates, and the walls.

He's one of about 25 Booker T. students who consistently participate in the school's chapter of OrchKids, the during- and after-school music-education-as-social-change program started by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in 2008. The Peabody Institute has been an educational consultant and community partner of the program from the start, providing resources such as sheet music, concert tickets, teaching artists, and interns; Peabody alumni also make up a fair share of its full-time staff. What began as a startup with 30 kids at one elementary school has grown to a program reaching more than 1,100 kids at six schools. The Booker T. site started up in spring 2014, when Brooks and some of his current bandmates were in fifth grade.

Image credit: John Dean

More people soon file in following a quick OrchKids-provided after-school meal in the cafeteria. Khandeya Sheppard, the OrchKids site manager at Booker T., and her OrchKids colleague Belinda Caesar come in with students trailing them and asking questions. Miss Kay, when's our next concert? Miss Belinda, do you know where my sheet music is? Tantrice McKoy enters with a small group of classmates, smiling and chatting as she takes a seat and starts putting her flute together. She eyes Brooks running through his bass line, says something to him, and then she and another flute player start playing together, a gentle duet against the room's rising ruckus.

Jared Perry, the Booker T. music director and an OrchKids teaching artist, enters with a chandelier of keys in one hand, his cellphone in the other, a few students stuck to his hip asking questions, and a smile sitting atop his tall frame. Today's going to be a cleanup day, he says, which means they're going to work through all their songs to find out what people know, what they don't, and what sections need work. There are only a few weeks left in the school year and they still have concerts to prepare for, including their graduation ceremony. And they need to figure all this out before they can finish Shakur's song idea—which, at the moment, consists mostly of the bass line he's popping off as everybody sidles in.

And then Perry's ear catches what McKoy is doing on her flute, and he quiets everybody down. Do that again, he asks Brooks and McKoy. The room stills as Brooks starts up his bass line and then McKoy and the other flutist come in with a gentle, lyrical response to the trombone's call. Perry watches, bobbing his head up and down, and rolls his hands to tell them to keep playing. After a few times through, he holds a fist in the air and they stop.

Video credit: Dave Schmelick

Since September, nearly every Monday the Booker T. OrchKids work on their brass band, an ensemble created during the 2016–17 school year. With a sound that calls to mind the New Orleans ensembles that have led second line parades since the late 19th century, the Booker T. brass band is made up of sixth-, seventh-, and eighth- graders playing a combination of clarinets, flutes, trumpets, and saxophone, trombone and tuba for the low end, and a small contingent of percussionists. They play some music composed for brass ensembles, as well as brass-band arrangements of popular songs, such as the Eurythmics' mid-1980s new-wave hit "Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)."

They also write their own material. A student brings in a melody or a beat pattern, and the entire ensemble workshops these ideas into songs. And since late November 2016, I've sat in on those rehearsals and attended their concerts. They played Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh's inauguration in December. They played in the lobby prior to a BSO performance at the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. They played "The Star- Spangled Banner" to open a meeting of the Baltimore City Public Schools board. And they played the winter and spring concerts for their school, classmates, and teachers. I've watched them shyly take solos in the music room and become lively entertainers onstage. I've witnessed them become a band.

"What do we think about that?" Perry asks the students about what they've just heard, and they nod their heads, bump fists. He wants them to consider where this bass line could go—is it the beginning of something or the middle? Does something need to come after it? What is it making them think about and feel?

"Tantrice, I think you got something there," he says to McKoy, and looks around at the rest of the band. "I'm loving where this is going."

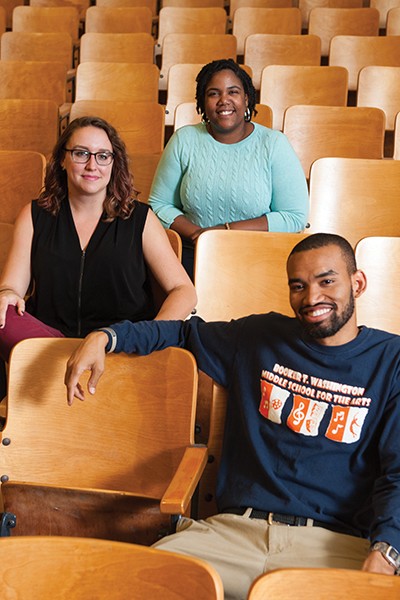

Image caption: From left: Mollie Westbrook, Khandeya Sheppard, and Jared Perry

Image credit: John Dean

Think of OrchKids as a music education nesting doll: There are multiple layers to how it interacts with students. During the school day, OrchKids teaching artists help school music teachers with their lesson plans. After school, the program offers meals and academic tutoring in addition to music workshops. Site managers coordinate the various in- and after- school schedules, as well as teach. Classically trained musicians have overwhelmingly run the organization since its inception. As students have matured through the program, OrchKids has cultivated a few different ensembles: a bucket band, a choir, string and wind ensembles, a youth orchestra.

The program didn't start out with the idea of creating a brass band, however. It was born out of a desire to engage students through classical music. "My original thought was there's 90 members in the orchestra and me, we should each mentor a child in the neighborhood," says Marin Alsop, who launched OrchKids in 2008 with $100,000 from her 2005 MacArthur Fellowship. Today the BSO's music director is also the director of the graduate conducting program at Peabody, but when she had this idea in the fall of 2007, she was newly installed at the BSO and wanted to see the orchestra play a bigger community role in the city it calls home.

The BSO put together a small team to figure out what a mentoring program should be. It included tuba player Dan Trahey, Peab '00, who became OrchKids' founding artistic director. OrchKids decided to collaborate with the Baltimore City Public Schools System, choosing a West Baltimore elementary school as its first site. Trahey and Nick Skinner, Peab '05, OrchKids director of operations, spent that first year at the school helping to raise money for a new freezer for the school's food bank, volunteering at winter coat drives, and helping out with managing the students. Initially, "people thought that Nick and I were undercover police officers," Trahey says. "We didn't have anything to do with music at that point, but we knew we wanted to help change the culture of that school, and that took us being in there."

Being there was half the battle, but it only works if the students want to be there, too. Booker T.'s brass band was initially hatched to bolster attendance. Perry says when he first arrived at Booker T. in 2013, he had only six band students to perform the school's winter concert. OrchKids arrived in 2014, and the extra help in the classroom boosted that number to 14. In March 2016, Mollie Westbrook, a site manager at a different OrchKids school, noticed how enthusiastically the Booker T. students responded to coming up with musical ideas during an annual songwriting project involving OrchKids and Peabody students. As an undergrad, she had played tenor sax in Indiana University's Marching Hundred band, and Booker T.'s students reminded her of that upbeat, brassy sound. "They have that energy," she says. "After that week I started thinking, Man, we should start a brass band."

OrchKids site manager Khandeya Sheppard agreed. She understood the appeal of having a musical project you wanted to do, and thought a brass band could get kids to after-school sessions more regularly. They'd still be working on fundamentals, but they'd also be writing music. She spoke with OrchKids staff, and they decided that one day a week during the 2016–17 year—on Mondays—might be a good initial trial.

Brass band music connected with the kids. "It's just better music," says Jelil Missouri, a clarinetist in the brass band. "Because some classical music is something that you just sit and listen to, but brass band, it's more of a dance music. You can move to it."

The brass band spoke to band director Perry as well. Born and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the trumpet-playing Perry learned military-style marching band while attending the Marine Military Academy in Harlingen, Texas. He was on his way to attend Berklee College of Music when his mom told him to stop off and see his sister at Morgan State University en route. Once he heard the Magnificent Marching Machine go off, he wanted to be a part of it. "We went to a football game and [at first] I didn't want to be there," Perry recalls. "And then I heard the band, and then halftime started, and I said, Oh. I had never been exposed to HBCU style of marching. They're dancing, having fun, playing all kinds of hype music. And that was a wrap."

Perry, 30, went on to earn his undergraduate music and teaching degrees from Morgan. "Hype" is his go-to word for those moments of life that put him in a happy place, and around the students that's typically a musical thing. When music makes you want to move, that's hype. When a student is gingerly finding his or her way through a solo and suddenly peels off an expressive flourish, that's hype. When the percussion students come up with a hip-hop funky beat, that's hype. When you hear something and you don't know why you suddenly feel good about being alive, that's hype.

A brass band could very well be hype. In spring 2016, the students learned "Don't Question It," a song by the Connecticut-based Funky Dawgz Brass Band, and added a second section and some lyrics to it. Called "FIYAH," it became the ensemble's signature song. It starts off with a slow, swinging horn section that heats up to a syncopated groove. The lyrics are simple—"We got that fire"—but imagine that sung by a bunch of middle school kids who stretch that final word into an emotive cry: We got that fiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiire.

Image caption: From left: Jalil Missouri, Dan Trahey, Cliff Wilson, Tantrice McKoy, and Shakur Brooks

Image credit: John Dean

The brass band "really caught on when we took 'FIYAH' and added to it to make it our own," Perry says. And the students drive that process. They'll suggest changing the beat, or add a melody, or increase the tempo—and so on. The adult musicians help them document it all, to note when, say, what they're asking for is breaking away from 4/4 time and moving into 6/8. But the compositional ideas are the students'.

Trombonist Sarah Lewandowski, a Peabody graduate student who worked with the brass band in the spring 2017 semester, says she's envious of the students' collective songwriting skills. "They write the notes, they write the rhythms, they decide what the parts are," she says. "I worked with Shakur a ton, and if they're working on a tune, Mr. Perry would say, 'Hey, we need a bass line,' and Shakur would just say, 'Got it.' And he'd go off and come up with something."

Songwriting isn't always part of classical music education, which emphasizes technical precision and reproducing exactly what is written on the sheet music over and over and over and over. I routinely heard Trahey, Perry, Sheppard, and Westbrook tell the kids that the notes don't matter when they're first learning a new piece. Or, don't worry about what the time signature says, play the time you hear in your head.

They're not downplaying technical excellence; they're teaching to a roomful of different skill levels at once. When some students have come through the program for a few years and some have just started, what's important is that everybody eventually gets to the same place in the music, in the same key, with the same emotive idea, in unison. Some kids need to work on their breath control, some need to work on fingering. Not hitting every note the first few times through a piece isn't failure. It's learning.

And when they're learning through the songs they wrote, the lessons not only tend to stick—they're able to teach each other. "I think by having them create their own stuff, they feel everything, the rhythms and the music, so it becomes part of them," Lewandowski says. "They can hear it in their head, they can sing it, and they can feel it. I don't think the kids realize how advanced that is. I don't think they realize that they have skills that people I go to school with don't have."

That process also brought a few of the kids out of their shells. Sheppard says that Shakur Brooks was very shy in sixth grade, and brass band has given him some confidence. Brooks was one-half of the band's low end for the 2015–16 school year, but then tuba player Cliff Wilson went on to high school.

"He had to be the go-to guy for the low-end section, so he had a leadership role in that ensemble," Sheppard says, adding that this responsibility gave him the confidence to say that he wanted to audition for the Baltimore School for the Arts—"something that probably was not in the cards for him before," she continues. "He began to think, 'I can actually do this.'"

It also gave Brooks the confidence to approach Perry with that bass line he had bouncing around his head. "I remember him coming up to me saying, 'Mr. Perry, I got this song, you gotta hear it," Perry recalls. "I think the next 'FIYAH' is going to be the song that Shakur made."

There are two moments in a band's life that seem to be the stuff of magic. One is when a group of individual musicians finally gels into a cohesive unit onstage, seemingly before your eyes. If you've ever spent a year or a few decades following local bands, you've witnessed this process before. One week a band sounds like a bunch of people who happen to be playing instruments at the same time on the same stage. The next week they're blowing the roof off the place. It can be like watching a foal wobbling around before standing up and galloping off.

The other takes place in rehearsal. It's when one musician plays something that sparks an idea in another. Wordlessly, they start talking to each other, and the other musicians listen, join in, and start throwing their own ideas into the mix. Nothing may eventually come of it, but when musical lightning does strike, you begin to think you know how it must've been when our early human ancestors, millennia ago, banging on rocks or something, discovered that syncopated beats ignited the brain-booty connection.

These wordless conversations pepper the brass band's rehearsals. Shakur Brooks experienced it when he heard a bandmate, nicknamed Low Rider, playing a simple drumbeat. "So Low Rider was on the set and I had my trombone and I started playing a scale," Brooks recalls, about how he first came up with his bass line. "And I said, Keep playing that, and I just started coming up with random beats at first. And then I came up with a bass line. And I was like, We got to keep that."

Image caption: Jared Perry leads a rehearsal in the Booker T. Washington auditorium.

Image credit: John Dean

Over the final Mondays of the school year, the Booker T. brass band shaped Brooks' idea into a rousing anthem. It's built around a series of three-note vamps that allow the band to treat tempo like silly putty, speeding up and slowing down around a melody held down by the trumpets. There's a percussive bridge where they sing the lyrics they wrote—"power and strength, together we're flying"—and McKoy's flute part plays a melodic role in the midsection.

"Shakur likes the type of music that pops," McKoy says. "You can really groove in and dance to it. You got to work around that. So I made that little flute thing, that back-and-forth call-and-response thing. I did that because flutes just play chords all the time, so I wanted to figure out something that is smooth and swings."

Brooks titled the song "Jelly," and a few weeks of collaboration workshopped it into a song sharp enough for the brass band to perform at both the school's year-end concert and graduation. "Playing in a band teaches social bonding, teamwork, discipline," says Matt Sakakeeny, Peab '95, a Tulane University associate professor of music and ethnomusicologist. Since the early 2000s, he's studied and performed with New Orleans musicians, and his 2013 book Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans dives into the social role of brass bands in 20th-century African-American music and the Crescent City's black neighborhoods.

In 2007, Sakakeeny got involved with Roots of Music, a nonprofit after-school program for students that is devoted exclusively to a brass band, the Roots of Music Marching Crusaders. He's currently working on a book project about the role of a brass band music education in New Orleans students' lives, one of the few instances I've located of a music scholar researching both contemporary education policy and the education outcomes of nonclassical music programs. He's doing so in New Orleans, where the public schools face challenges similar to Baltimore's—decades of white flight, economic mismanagement, etc. In his 2015 paper "Music Lesson as Life Lesson in New Orleans Marching Bands," he writes that, yes, music education provides a basis for a career as a professional musician but also that the time spent in band room is productive for all students, whether they pursue a music career or not.

Booker T. Washington is one of those Baltimore City schools where the students are referred to as "at risk" or "challenged," the terms applied to kids growing up in families that are low-income, single-parent, and/or nonwhite. The middle school shares a building with the Renaissance Academy, a public high school in the news over the past few years both for its operational challenges—the school district was considering closing it—and for the deaths of three students in the 2015–16 school year. In June 2016, a 13-year-old Booker T. student was fatally shot about a half-mile from the school. In February 2016, the University of Maryland released the results of a violence survey that queried 209 Booker T. and Renaissance Academy students. Forty-three percent reported witnessing physical violence at least once a week. Thirty-seven percent reported knowing someone killed before the age of 19.

Such economic and public health challenges are rooted in the greater disinvestment that has segregated Baltimore's black communities from its white ones for a century. That bigger picture, however, isn't mentioned when the news talks about Booker T. And knowing how other people view your school can weigh on students.

"You know how you've got regular classes, you've got people stuck there who can't escape, but you come to band, you can kind of escape that world," McKoy says. "It's people that you like and can connect with. I'm more open and I talk to people more [in band]. Like, Shakur. I would never talk to Shakur before, I would just walk past him in school. We started talking in band, and now we're best friends."

OrchKids believes that music education can change a person's life; with the brass band, the program was flexible enough to see that it doesn't have to be classical music that does that. Sakakeeny notes that in New Orleans, marching band music is what kids want to play, but conventional music education too often focuses on European classical tradition. "There's a presumption that classical music resides at the top of a pyramid and all other styles of music are subservient to it," Sakakeeny says. "But all styles of music have their own metrics of excellence and take confidence to play."

"OrchKids has shown me that when you have the support that other more affluent neighborhoods have, [students] will excel," Perry says, adding that his students often come to class and tell him about something going on in their lives. An addict nodding off on the bus. Somebody they know who was murdered.

"Can you imagine growing up with this? I can't," he says, and alludes to a Tupac Shakur lyric about the rose that grew from concrete. "The petals around them are torn, but these kids, they're still beautiful. They curse, yes, they fuss, they fight. They're going to do different things that we wouldn't do. But guess what you're here for as an adult? To provide a different view and say, 'This isn't what life is only. Yes, this is your reality, but guess what? There's another reality.'"

OrchKids celebrates its 10th anniversary in 2018, and executive director Raquel Whiting Gilmer says the theme for that anniversary is possibility, promise, performance.

How effectively OrchKids is using music as an agent for social change is the challenge it, and nonprofit arts endeavors in general, faces. In American cities, we're a few decades into living with arts-education budget cuts while trumpeting the arts and entertainment as engines driving urban renewal. We want the arts to be a healthy part of our economic base, but we can't afford to sustain them in schools.

Nonprofit organizations have stepped in to fill that hole. And in Baltimore, that's not only OrchKids. Forty-five OrchKids are also in Peabody's Tuned-In program this year, and many of them also get music instruction through the Baltimore School for the Arts' TWIGS program. The website of El Sistema USA, a national alliance of programs inspired by Venezuela's government music program that works to lift kids out of poverty through classical music instruction, lists 129 organizations in the U.S., including OrchKids and Tuned-In. It takes a village of public-private partnerships to provide what private schools do—and what American public education once believed should be accessible to all.

Education is still overwhelmingly measured in test scores, and those qualities Matt Sakakeeny talked about students learning in the band room—bonding, teamwork, discipline—don't conform to standardized tests. In the absence of such data, the students themselves often become the living examples for what an arts organization can do.

And if an organization that aims to use music to change students' lives is pointing to its students as proof of its success, it better be listening to them—which Sheppard credits OrchKids doing in supporting Booker T.'s brass band. "That [decision] is part of listening to the community as the stakeholder," Sheppard says. "The kids are the biggest stakeholder in this whole thing."

This year, Booker T. sent three student musicians to the Baltimore School for the Arts, the largest group since Perry arrived. Trombonist Brooks and clarinetist Missouri graduated from middle school and are now BSA freshmen, and tuba player Wilson, who graduated from Booker T. in 2016 and went to a different high school last year, auditioned and transferred to BSA this year. McKoy plays flute in the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute's celebrated marching band.

"I love making music for people to hear," Brooks says. "It's my favorite thing to do. I feel like brass band is the reason we get so many opportunities, how we get to come together as a whole family." He adds that, after college, he wants to put together a working brass band— with his Booker T. colleagues. "We've got a lot of brilliant people in our band," he says. "I feel like I've known them for most of my life, and I want to know them for the rest. I want to make music with them."

Does imagining a musical future happen in a child's mind if that child doesn't have the chance and encouragement to play? Maybe. Maybe not. "You are used to people saying, 'You got an A, I am really proud of you,'" Sheppard says. With the brass band, the students are hearing, "'You are playing music and I am really proud of you.' That is it, that's what they need to hear. They are playing music and people are proud of them."

In December, the brass band was invited to play in the lobby of the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall before the BSO holiday program that featured a Duke Ellington arrangement of The Nutcracker performed with Step Afrika dancers. "It was our first big gig," Westbrook says.

"It was a big deal because it had donors there and symphony people were walking by," Sheppard recalls. "The kids did not pay attention to any of that. They just knew they were coming to perform and this was their gig. It was not a gig that they were performing with any other OrchKids site. Man, did they put on a show."

Over their clothes, the students wore OrchKids T-shirts that ensembles often use for concerts. They lined up in an arc at the foot of one of the stairwells leading up to the hall's grand tiers. Perry introduced the group, letting everybody know that they were playing music the kids wrote. And as he does whenever the band plays, he turned to face the musicians, and with his back to the audience made a funny face that only the kids would see. It's a goofy icebreaker, reminding the students not to think about all those people holding drinks looking at them. Right now, this is us, just like we do in band room. He raised his hands and silently counted off. And then the brass band foal stood up and took off.

"After that, everybody's eyes were, like, oh my god," Sheppard says. "We started getting called to perform for everything. And the kids started taking ownership of the ensemble. They started holding each other accountable, saying, 'We have rehearsal today, where you at?'"

Brooks, McKoy, and Missouri smile when thinking about that show. In part, because the concert was at night and their parents could come. In part, because of how excited everybody was. And how their saxophonist bandmate started dance-strutting across the floor. And how a small child in the audience started to dance with him. And how the notes don't matter, until they do. And how you want to play the music you hear in your head when you wrote it with your bandmates. And how you are playing music and people are proud of you.

"It was a great experience," Brooks says. "We were giving so much energy. We had them moving. We got them turned up. We were hype."

Posted in Arts+Culture