Anna Scott hopped aboard a barge on a recent sunny fall day to show a Baltimore celebrity what she's been up to. Armed with three plastic cubes—each one sporting googly eyes—the doctoral candidate in Earth and Planetary Sciences was visiting Mr. Trash Wheel, a water wheel in Baltimore's polluted Inner Harbor that, besides reeling floating trash into its dumpster, has garnered popularity for its own 4-foot-tall googly eyes.

Image credit: Laurent Cilluffo

Scott and collaborators Yan Azdoud, a former postdoctoral fellow in Civil Engineering, and Chris Kelley, a doctoral candidate in Environmental Health and Engineering, are members of the Baltimore Open Air Project, and together they've developed WeatherCubes, low-cost tools to collect heat and pollution data around Baltimore. With $40,000 from an Environmental Protection Agency grant, matching funds from the Johns Hopkins Environment, Energy, Sustainability and Health Institute, and four workers from the job-training nonprofit Civic Works, the team built 250 air quality monitors and is working to deploy them at Baltimore schools, nonprofits, private residences, and yes, even a trash wheel.

Why do it?

Baltimore's collective air quality is among the worst on the Eastern Seaboard. But because of differences in neighborhood industries, vehicle types, and amount of green space, air quality varies considerably across the city from neighborhood to neighborhood. Scott, Azdoud, and Kelley hope the data collected from their devices can be used by scientists, policymakers, and residents to determine why air quality varies so much, whether it's a function of urban features like trees or proximity to highways, if and how the city can improve the situation, and what's the air quality in individual users' neighborhoods.

How they work

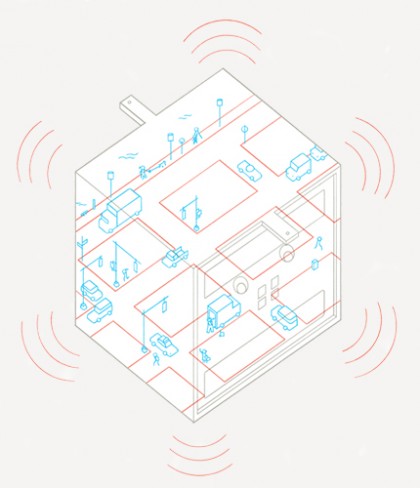

The white plastic WeatherCubes, about 1 cubic foot in size, are made to live outdoors: they're water-resistant and solar-powered. A tiny fan sucks air inside, where its temperature and humidity are measured. Additional sensors attached to a custom-designed circuit board collect data on pollution levels four times per hour, and then transmit the information over Wi-Fi to a cloud service accessible to researchers.

What makes it cool

Existing tools to measure pollutants, designed to meet federal regulations, are very accurate—and very expensive, costing between $100,000 and $200,000 per monitor. The Johns Hopkins team sought to bring the price down, building theirs for less than $500, to supplement the data from the high-quality, costly monitors and assess relative air quality between neighborhoods.

"Our device fits into this new trend of making devices that are 'smart,' or capable of talking with the outside world," Scott explains. "It hasn't been cost-effective until recently." And while it's important for scientists and public health officials to be able to track air quality for research and regulatory purposes, the data will soon also be available to individuals interested in understanding their own personal exposure on the local level. "People really want to know data that reflects their existence," Scott says. "Technologically, now that's possible."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged air pollution, environmental health