On an unseasonably warm mid-December day in 2011, Melodie Liddle took her two dogs, Copper and Pirty, for a long afternoon walk in southeastern Indiana's Versailles State Park. She frequently brought her "kids" to this popular spot, especially in winter when the crowds shrink. Toward the end of the trip, the dogs began to pant, so Liddle steered them down to a creek for a drink and a sniff-around. Moments later, she heard Copper frantically yelp and then start to thrash in the water. The dog, a 10-year-old hound mix that she had rescued from a neglectful home, had become ensnared in a Conibear trap, a metal, bone-crushing device used by trappers to kill raccoons, beavers, and other small animals. The trap, hidden in a nondescript wooden box on the water's edge, had clamped onto Copper's neck, collapsing her airway. Liddle tried to free her but could not pry open the steel bars. She screamed for help. Frantic, she tried to call for assistance but had no cell reception in the park. After several minutes, Copper went limp and soon died in her owner's arms.

Liddle subsequently learned that the trap had been set by a park employee to control the park's raccoon population. Liddle sued for damages, claiming that the Indiana Department of Natural Resources failed to notify the public that throughout the park it had hidden potentially deadly wildlife traps. She hoped her case would put an end to the practice and save other pet owners from heartbreak. She retained an animal rights attorney, and for the last three years the La Porte, Indiana–based Center for Wildlife Ethics has litigated the case.

Image credit: Brian R. Williams

Anne Benaroya, the center's director of litigation, says that in the eyes of Indiana law, Copper is considered property worth what someone would be willing to pay, perhaps a few hundred dollars, more if the animal had breeding potential. But what price can you put on the loss of a beloved companion, especially one you had to watch suffer and die? Benaroya says, "We want to change the way damages are valued. We're arguing that the court should acknowledge the client's evaluation of her pet, and take into evidence the objective measure of her investment in the animal—how she fed the dog, paid for vet care, and fulfilled all her pet owner duties—plus the emotional pain and suffering she's been through. There should be value on the animal-owner relationship." To help pay her legal expenses, Liddle recently launched a GoFundMe page for a case that will soon enter its fifth year.

If all this sounds like a bit much for one dog, you probably don't own one. David Grimm, a lecturer in the Krieger School's Writing Seminars and a science writer, is no stranger to this humanization of pets. He's been writing about the phenomenon for the past eight years and is the author of Citizen Canine: Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs (PublicAffairs Books, 2014), which traces the journey of dogs and cats from wild animals to family members, both in our homes and in the law. While livestock have been considered property since the days of the Roman Empire, pets didn't begin to earn this status until the late 1800s. Today, dogs and cats are quasi-citizens with more legal protections than other animals. The modern status of dogs and cats is quite a leap from 15,000 to 30,000 years ago, when their wild forebearers ventured into human villages, first to forage for scraps, then to eat out of our hand.

The American Pet Products Association estimates that Americans own nearly 80 million dogs and some 85 million cats. Approximately 44 percent of all households in the United States have a dog, and 35 percent have a cat. The majority are treated like family, even children. Glance at your Facebook or Instagram feed—you're sure to encounter all manner of photos and videos posted by proud owners to update Fido's or Fifi's latest exploits or well-being. Here's Baxter the bulldog dressed in team colors watching the game. Miss Cuddles perched on top of the recliner for a nap. The two black Labs fresh from a morning run. Our cars and trucks advertise our pet love, whether it's rear window stick-figure decals of pooch and kitty lined up alongside the human children, or a "My Grandchild Is a Tibetan Mastiff " bumper sticker.

We spare no expense for our four-legged friends. The APPA reports that in 2016, Americans spent $28.2 billion on pet food, $14.7 billion on supplies and over-the-counter medicine, $16 billion on vet care, and $5.8 billion on services like grooming and boarding. But these numbers tell just half the story. These days, generic kibble and chew toys have become antiquated. Pet store shelves feature pet chow that includes organic vegetables, gluten-free biscuits, and grain-fed beef. Does your schnauzer prefer duck or bison? The pet market has been transformed by the humanization of animals. Our critters wear their own Star Wars hoodies or sporty sunglasses, and enjoy nonalcoholic doggy beer and cat wine. Pinot Meow is a thing, a catnip-based liquid feline treat. Dogs are getting lawyers. Cats are getting ACL surgeries. Major cities have Doga classes—yoga for dogs.

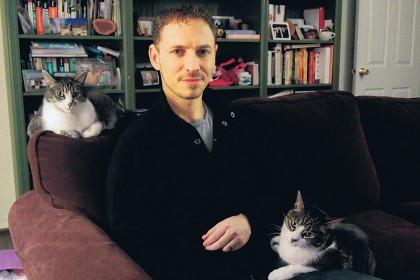

Grimm, who earned a doctorate in genetics from Yale, has continued to write about society's evolving relationship with pets since Citizen Canine, and is a frequent commentator on the subject for television, radio, and podcasts. He says his path from young science journalist to in-demand pet expert began when he moved to Baltimore. He and his fiance?e decided to adopt two cats from a Humane Society shelter. Among the available animals sat twin kittens, Jasper and Jezebel—then called Jack and Jill—whose tiny heads and fuzzy white bellies warmed their hearts. They paid $130 for the pair.

Image caption: Science writer David Grimm with his pet cats, Jasper and Jezebel

Shortly into his new home life, Jasper, once an energetic kitten, started to slow down and ignore both toys and his adoring owners. Concerned, Grimm took the cat to the vet, where the animal was diagnosed with acute renal failure. Jasper, they were told, might have only days to live. What happened next was a trip to a local pet hospital that was outfitted with a state-of-the-art intensive care unit, where Jasper was seen by an internist and a nephrologist for all manner of tests, including an ultrasound and blood-chemistry profiles. A $20,000 kidney transplant became a possibility. But after three days in the ICU hooked up to a catheter and IV antibiotics, Jasper mysteriously got better, although the couple was told he'd have permanent damage to one kidney. The initial ER stay cost upward of $3,000, for a cat that had cost a mere $65. "At that time in our lives, $3,000 was a big hit to the budget, but we saved the cat's life. And I would do the same thing today," Grimm says. "Some people might still say that going to such lengths is ridiculous, but it's become the new normal. I might have been laughed out of a room 30 or 40 years ago for doing what we did. But today, we live in a world of doggy bakeries and pet day cares."

Before they became pets, domesticated animals had practical jobs to do. Dogs acted as sentries, assisted in hunts, and later herded livestock. Cats guarded grain and other food supplies from rats and mice. That status remained the norm for hundreds of years, until the Middle Ages when cats, and to a lesser extent dogs, suffered a serious PR crisis. Cats were associated with witches and heretics. Pope Gregory IX labeled black cats agents of Satan in his 1233 Vox in Rama, which effectively authorized their slaughter by the thousands. The feline hysteria would continue for centuries, and some historians claim tens of millions of cats were massacred during this period. The 17th-century French philosopher Rene? Descartes declared animals mindless and soulless machines that could not feel real pain, an attitude that paved the way for horrific experiments on living creatures. Dogs were mostly viewed as spreaders of filth and disease.

Domesticated critters made a comeback in the Victorian era and early 1900s, a period that saw a rise in sentimentality toward them, owing partly to a backlash over abuse and their vivisection in research studies, and partly to a new consideration of them as sentient beings with emotions. Mark Twain played his part with his 1903 short story "A Dog's Tale," initially published in Harper's, depicting the life of a family as viewed by a canine. The introduction of flea-and-tick products in the 1880s, then Kitty Litter in 1947, enabled people to keep cats and dogs indoors. The pet retail industry was born.

"There was this paradigm shift during this period. Animals that once wandered the neighborhood and slept outside now got to sleep on the couch," Grimm says. This period also saw a rise in pets being spayed and neutered. No longer solely intended for breeding or work, dogs and cats became companions and family members. "We are increasingly turning toward our dogs and cats to amuse us," he says. "We have come to rely on them for company. There is a physical and emotional bond."

Now, a growing number of advocates seek greater legal status for pets, reasoning that these animals should essentially have some say in what happens to them. If a cat has a tumor, does it have a right to treatment? Should an owner be fined for refusing to take a dog out for walks? This movement has been spurred on by growing scientific evidence of animal cognitive and emotional capabilities. Emory University neuroscientist Gregory Berns, author of How Dogs Love Us: A Neuroscientist and His Adopted Dog Decode the Canine Brain (New Harvest, 2013), has used MRI machines to scan dog brains and found compelling proof that they empathize with human emotions. In 2015, a team of neuroscientists in Japan released a study, published in the journal Science, that shows dogs really do love their owners. In two different experiments, the team measured levels of the hormone oxytocin in dogs and their owners as they gazed into each other's eyes. In both animals and humans, the eye contact elevated the so-called love hormone, which plays a vital role in female reproductive biological functions. A previous study had found the same outcome when humans and animals touched. It's not unlike the mother-infant bonding, where a look into a child's eyes reduces anxiety and triggers a brain-chemistry reward.

Today, there are animal cruelty laws in all 50 states, with penalties as severe as $125,000 in fines or a year or more in prison. Damages for emotional distress have been awarded to pet owners who observe another human intentionally injure or kill their animal. Dogs and cats have been made beneficiaries in wills. Pamela D. Frasch, assistant dean of the Animal Law Program at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, and executive director of the Center for Animal Law Studies, says that dogs and cats have more protections than any other animals because of the special relationship we have with them. While states still regard pets as property, Frasch says lawmakers are beginning to recognize that we clearly don't treat our pets as if they were a table or chair. In January, Alaska became the first state in which judges are required to consider animal welfare and well-being in cases where divorcing couples have a pet. "The court now has to consider the best interests of the animal, and who would be the better custodian," Frasch says.

People have also begun to write pet trusts, Frasch says, to make provision for what will happen upon the owner's death. "In the past, a family member could step in and simply say Fluffy needs to be euthanized, or send this dog to a research facility," she says. Now there is a mechanism in many states to give fiduciary responsibility to someone who will respect the wishes of the owner. The legal system, she says, has become averse to the killing of a healthy, adoptable pet.

If pets are on the road to citizenship, some want to put this car in neutral. While veterinarians generally benefit from our treating dogs and cats like children and taking them for regular checkups, some vets worry that granting animals personhood could lead to more malpractice suits when something goes wrong. The scientific community worries about the future of using animals in research. Already, chimpanzees have been phased out of biomedical studies, and other nonhuman primates might follow. Can and should we give lab mice legal rights? The livestock industry also has concerns about the rights being given to dogs and cats filtering down to cows and chickens.

Image caption: An act of Congress in response to Hurricane Katrina mandates that federal and state governments must incorporate pet safety when designing disaster plans.

Image credit: Jocelyn Augustino / FEMA Photo Library

Most of Grimm's stories involve animal welfare. In 2009, he wrote "A Cure for Euthanasia?," which followed the quest to develop birth control for cats and dogs in an effort to curb the mass killing of these animals in shelters and on the streets around the globe. He has also written extensively about how Hurricane Katrina effectively turned pets into people. In the hours and days after the storm hit, the public witnessed life and death struggles played out live on television. Grimm says nearly half of New Orleans homeowners stayed in their houses because of their pets. When boats and helicopters arrived, many rescuers told the homeowners, "We're here to save you, but the animal is staying." Many owners stayed with their pets, Grimm says, and ended up dying. Abandoned animals starved or drowned. In response to public outcry, Congress in the fall of 2006 nearly unanimously passed the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act, which put in writing that federal and state governments must incorporate pet safety when designing disaster plans. Red Cross shelters now cannot turn away cats or dogs. Emergency responders are compelled to evacuate pets as well as people, and find ways to transport them to safety.

The business world has adapted to our animal love, too, Grimm says. More and more hotels allow pets. In just one Baltimore suburb, more than 60 restaurants welcome dogs at outdoor tables. Cats and dogs weighing 20 pounds or less can travel on many Amtrak routes, and for a modest extra cost, many airlines allow dogs and cats to fly in the main cabin, provided they are in a carrier. Some small businesses offer pet insurance to employees, or "pawternity leave" when they get a new puppy or kitten or rescue an animal. Some companies allow employees to bring their pets into work. "For many of these places, it's simply a smart business move to cater to pets," Grimm says.

He argues that social norms are fundamentally transforming our relationship with these animals and reshaping the fabric of society. Frasch says while dogs and cats have taken baby steps to achieve some of the rights of humans, they are still property and there are strict limitations on their rights, for now. "Still, I could foresee an enhanced property category of limited rights," she says.

Grimm, whose home also includes his 4-year-old twin daughters, says his cats, who recently turned 12, are both doing well. They should be. They get top-of-the-line cat food, veterinarian care, and attention. "We max out on everything we do for them to make them happy," he says, but he does draw the line on humanizing. He once bought Jasper a bow tie, thinking he would look supercute. He did, Grimm says, but the cat sure wasn't thrilled, so that ended the wardrobe practice. Pets might be getting the rights of people, but they probably don't want to look like us.

Posted in Politics+Society