Rosa Pryor-Trusty saw the posters all the time when bopping around Baltimore in her car. They were stapled and posted to telephone poles, street sign posts, walls, wherever they might catch the eye. No two were exactly alike, but they shared enough visual similarities that she could tell they all came from the same place. And when Pryor-Trusty needed to have posters made, she knew exactly where to go: the Globe Poster Printing Corp., based in East Baltimore. "I wouldn't have thought of anyone else," Pryor-Trusty says. "As far as I was concerned there's hundreds of printers out there, but they couldn't do what Globe did."

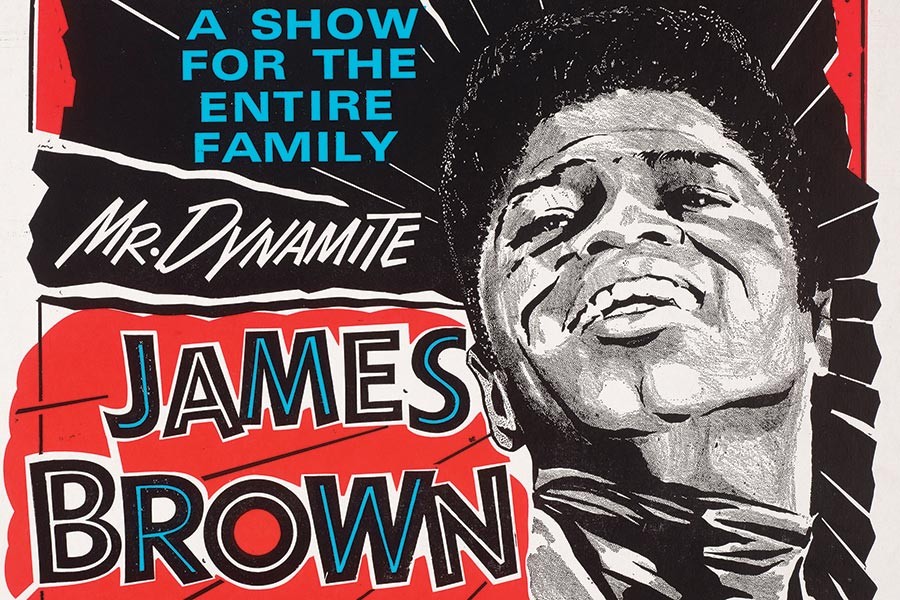

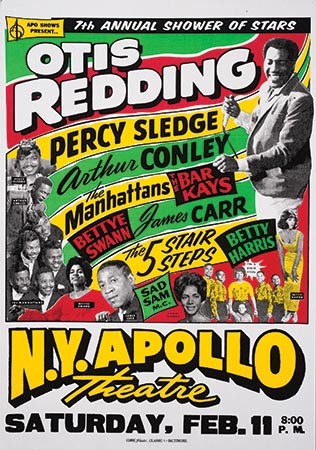

What Globe did was grab your attention. The company started in 1929, making posters for movies just opening in theaters, traveling carnivals and circuses and regional fairs, demolition derbies and motorcycle and automobile races, burlesque shows, and political campaigns. But when blues, R&B, soul, and early rock 'n' roll artists started touring the country, Globe became a go-to source for them. Tall black lettering announced the performers—James Brown, the Jackson 5, B.B. King, the Rolling Stones—next to headshots of increasingly famous faces. Because Globe worked fast and cheap, it often relied on the more affordable ink colors, including hot Day-Glo hues that popped out of a city's drab landscape. For the multiact bills of early R&B tours, Globe would stack five acts' names and pictures on a single poster in horizontal bands of highlighter yellow and inflamed pink.

Chances are you've seen a Globe poster or a design copping its indelible style. They're collector's items that can fetch a few thousand dollars on eBay. Some are in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 1960s and '70s Baltimore, they were the best way to let the city's African-American population know who was hitting a Pennsylvania Avenue club that weekend. "As far as I'm concerned it was the only way," Pryor-Trusty says. Today the 73-year-old Baltimore native is the "Rambling Rose" entertainment columnist and writer for The Afro-American and The Baltimore Times, and author of African-American Community, History & Entertainment in Maryland (Xlibris, 2013), a look at popular black entertainment from 1940 to 1980. She started singing and playing piano and saxophone with bands in her early teens, and as the leader of Rosa and the Twilights toured as an opening act for Sam Cooke, the Shirelles, and Jimi Hendrix. Nat King Cole gave her the nickname "Rambling Rose" during this time, and it stuck.

In the early 1970s, she became a booking agent in the Baltimore-Washington region. She says she would "drive around the city just to see who was performing. As I was traveling, doing errands, or going to a club, I'd look for the posters. I stopped and got out of my car and read them, made notes, because I want to go to the show."

Image credit: Image courtesy of Globe Collection and Press at MICA

Today, thousands of Globe's posters reside at the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries, along with all the company's business records. In 2011, roughly a year beyond when Globe Poster closed after being in business for 81 years, the Maryland Institute College of Art bought a sizable portion of its stuff—all its business records, which documented the creation of a poster from order to proof to finished product, and everything used to make it, including photo cuts, presses, tools, and case after case of movable type.

In all, 16 trucks were required to move the Globe collection from the East Baltimore shop to MICA's storage warehouse in Reservoir Hill, where Emily Hikes first encountered it in May 2015. Hikes is the Sheridan Libraries' Globe Collection archivist, a two-year, grant-funded position. She has been tasked with organizing more than 8,500 posters, more than 150 cubic feet of business records, and more than 12,500 photo cuts used to print the posters.

There are stories and histories lurking inside the paper trail left by a printing company that survived from the silent movie era through the dawn of social media marketing. But scholars, journalists, and the general public can't start looking for them while the collection is packed in boxes stacked four high in a Baltimore warehouse. "I've done five big projects like this," says Hikes. When she was first shown the collection, she and her interns did a quick survey of the posters and paper ephemera, then moved them to a storage room on D-Level of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library for sorting and cataloging. Encountering a seemingly impenetrable amount of stuff and making sense of it is the archivist's norm. "You get shown to a mess," Hikes says, "and people say, 'Fix this.'"

Mary Mashburn is a printer and MICA faculty member who was part of an advocacy group instrumental in lobbying the art college to buy the collection. (She is also a former associate editor of Johns Hopkins Magazine.) Mashburn recognized early on that the Globe collection had historical value—and that MICA might not have the capacity to archive it properly. "There's a lot of paper ephemera, a fairly decent portion we'd love to teach with because it's incredibly valuable for art students," she says. When Allison Fisher, a former MICA student who is now coordinator of the collection, and some students pulled some of Globe's cuts and type from the warehouse to make a small teaching studio, they didn't know what all the collection contained, and MICA didn't have the resources to do the painstaking archival work that goes into organizing and cataloging it for scholarly use.

Mashburn reached out to Jordon Steele, the Hodson Curator of the University Archives at the Sheridan Libraries. For Steele, the collection represents material important to both historians of the 20th century and the city Johns Hopkins calls home. "We're really interested in being a partner in the stewardship of this collection, both as an archivist who recognizes the enduring scholarly appeal of it but also just as a citizen of Baltimore," Steele says, complimenting Mashburn for realizing "this collection could be used in overlapping but specific ways by MICA and our students. As an arts school, their job is primarily to produce creative works, so MICA students will be inspired in different ways than a student in an African-American studies class who wants to look at a certain aspect of the Globe archive to research the history of the black experience in America."

Given that Hopkins didn't own the collection, he wasn't sure how the schools could partner on it. But he did wonder whether the collection might be a candidate for a major archival grant. In 2014, MICA and Johns Hopkins applied for a two-year Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives award from the Council on Library and Information Resources to hire an archivist to process the collection. They were awarded the grant in 2015, and the library hired Hikes that spring. Since then, she and two interns have been cataloging the collection's paper ephemera and the photo cuts. They've been generating databases and a finding guide to make the collection's items findable through general internet searches.

The size and variety of materials make archiving the Globe collection an unusual process. The business had its own record-keeping system that Hikes had to figure out. Fortunately, she could consult with Bob and Frank Cicero, the brothers who ran Globe during its final decades. "I think what was very, very helpful for Emily was that Bob and Frank were around," Steele says. "They have a very idiosyncratic way of running their business, and a lot of the processing of archival collections is anthropological. It's about understanding and respecting the way in which people ran their business and, therefore, the way in which the record of that activity was collected."

Bob Cicero, in his late 60s, has the lean physique and taut arms of somebody who worked with his hands all his life. His father, Joseph Cicero, started working at Globe in 1934 and, save for a stint in the Navy in 1944 and '45, stayed his entire life. The elder Cicero bought the company from one of its original owners in 1975 and continued coming to the shop after he retired in 1988. Bob started at Globe in the early 1960s, and he and his two brothers took over the day-to-day operations after their dad retired. As a result, he's full of stories that come from being part of a family-owned business that worked with some of the bigger names in music before they became icons. He recalls speaking to Tina Turner one time when she was phoning in her poster order; her phone number is still in the Globe Rolodex, a pair of mammoth rotating files. He says Motown Records would place an order for 3,000 to 4,000 posters for a summer tour, and the shop would first make a basic design that left blank spaces so they could add dates and venues for different stops along the tour.

Over the years, Globe accrued a catalog of images for repeat clients as promoters mailed the shop new publicity photos. Photographs were turned into halftones that were used to create the photo cuts—metal plates attached to blocks of wood—used in the printing process. By the 1970s, Cicero says, some artists started showing signs of age, and they started asking Globe if, well, the company had any of their earlier photo cuts lying around that they could use for a new poster. "We'd ask, 'You want to use the old cuts?'" Cicero says, adding that Globe kept every cut it ever made. "When they get to their 50s they look old, so they try to get their 20-year-old [cuts]. Then when they get to 70, they want the [current] ones because now they look cool."

Mashburn jokes that Cicero, now a part-time MICA printmaking teacher, is part of Globe's living archive. "When you got 40-some years of pumping out 15 or 20 different posters a day, you got to know something," Cicero says. "If you didn't, you wouldn't be in business for so long. The one thing [customers] always said is that it's got to be readable, it's got to be out there with the multicolor, and cheap."

Globe was a volume business, turning out upward of 20 posters a day for nearly 80 years. The 8,500 posters that Hikes cataloged represent a minor portion of the company's entire output, as it kept only a modest number of the posters it made from the 1940s to the '70s; the bulk of the archives dates from the 1970s on.

Globe's vast collection of photo cuts, however, contains a more extensive record of all the company's clients. Since September, Hikes and MICA undergraduate interns William Chapman and Amber Rhein have been sorting and cataloging these cuts to create a teaching archive to be used by MICA students and print artists. Hikes estimates the Globe collection contains about 12,000 cuts. They were stored in cardboard boxes, and each box had a date written on the side in magic marker. In November, these boxes, stacked three to four high, formed a rectangle about the size of a large living room in the warehouse where Hikes and her interns work. Each box receives an item number and description. That description may be as precise as "James Brown, 1968," owing to handwritten information on the back of the cut. But not all the cuts have such written identification. In some instances, Hikes and the interns know who the image is because they remember it from the posters. But that's not always the case. Globe made posters for scores of now famous musicians, but it also worked with bands and artists who didn't go on to fame and fortune. If those lesser-known acts aren't identified on the back of the cut, they might go into the database simply as "R&B singer, 1966."

It's a patient process. In early December, Chapman sits at a desk with a row of about 12 wooden blocks lined up. They're roughly three-quarters of an inch thick and of various widths and heights. Some look to be about 5-inch squares; others, rectangles roughly 4 inches by 8 inches. On one flat side is an etched metal plate of an image. Chapman stands them on their thin edges in a row, and with a small brush he applies a layer of adhesive to the edge and then affixes a small piece of paper to the photo cut. Each piece of paper includes a unique number in the 100-page (and counting) spreadsheet being created to identify and track every cut.

It takes about 15 minutes for Chapman to work through the small row of cuts on his desk. Once the resin adhesive dries, he places the cuts inside acid-free boxes lined with an archival quality polyethylene foam called Volara. Each box also receives an identifying number. Twelve down, a few thousand to go.

Eventually "people will be able to search for whatever they can think of and retrieve a cut," Hikes says. "Maybe I want to see all the cuts from 1971, or maybe I want to see a date span of all the R&B cuts. You'll be able to search the posters in a similar way. We did a little bit better with the posters than we are with the cuts because the posters spell it out for you. We can't confirm as much information [on the cuts] as we did with the posters."

It's these lesser-known and unknown faces, figures, and bands that will be of the most interest to future scholars. Popular music history is told through the James Browns, the Jackson 5s, the Martha and the Vandellas. Human history is told through the lives of the commoners, people who perhaps gave a singing career a shot for a few months and then went back to their daily lives. Globe's posters and cuts contain thousands of those people. "The ones I always like to talk about are the one-timers that nobody ever knew," Cicero says. "There's a lot of onesies in [the collection] that nobody would ever know unless it was archived like it is now. There are some people in there, I mean, you might sit and laugh if you look at them now. Yet they thought they were the greatest artists in the world, and maybe they were."

Image credit: Image courtesy of Globe Collection and Press at MICA

Celene Aubry, the manager of Hatch Show Print in Nashville, Tennessee, is sure those stories are there. What Globe is for R&B, soul, and funk artists, Hatch is for country and Western music. It opened in 1873, and from 1925 to 1992 operated right behind the Ryman Auditorium, the former home of the Grand Ole Opry. Today, it's still a working print shop, classroom, and gallery, operating as part of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, and Aubry says researchers routinely contact Hatch. A filmmaker working on a documentary about Keith Richards recently stopped by the shop to see plates of posters for the Rolling Stones. Hatch has the ones used to make the poster for the first time the Stones played Nashville in 1965 and many of the times they returned, including their last visit in 2015.

Aubry mentions some posters Hatch made in the 1950s and '60s for a magician based in Kentucky who used to tour regionally. She put an image from one of those plates online, a photo that featured the magician and his assistant, a young woman. The assistant is still alive and lives about an hour away, in Murfreesboro. "She came up and visited and I showed her the plates," Aubry says. "And she told me, yep, she worked for him for three years while she was in college. The magician was the dad of one of her high school classmates. He has passed but he had a son, and she told me, 'He's a magician and a clown and lives in Kentucky—do you want me to put you in touch with him?' I told her to hold that thought because we're going to want to do that.

"By making this stuff available [to the public], it's like showing snapshots of our social lives to generations who weren't around at the time," Aubry continues. "These stories come out of the woodwork when people see these posters, and when those [Globe] posters get out there, you're going to get some incredible feedback from the community."

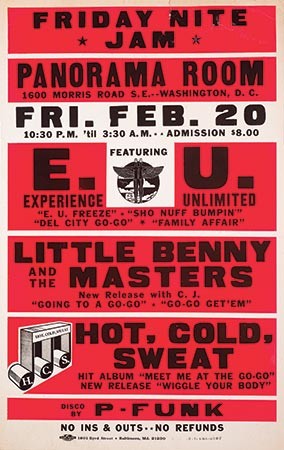

Cicero figures there's an untold history of R&B in Globe's collection, as the company made posters for a wide swath of promoters advertising concerts in the South in the 1960s and '70s. "We did a lot of R&B in Dallas, a lot in Fort Worth and New Orleans," he says. "We did some in Tennessee, the Deep South, Georgia, and all that."But around that time another musical genre was beginning to provide some of Globe's regular customers. The go-go posters in the Globe archive are good examples of the untapped cultural history the collection contains. Go-go is a variety of dance/funk music that began percolating out of Washington, D.C., in the late 1960s and '70s. By the 1980s, go-go had become the party music for ensuing generations of black Washingtonians, but it rarely traveled outside the city's metropolitan area. The late Chuck Brown, go-go's godfather, scored a modest hit in 1979 with his song "Bustin' Loose," and Experience Unlimited, aka EU, earned a No. 1 spot on Billboard's Hot Black Singles in 1988 with "Da Butt," which appeared on the soundtrack to Spike Lee's School Daze.

Go-go promoters didn't seek out mainstream, predominantly white publications to reach its audience, says Natalie Hopkinson, a Howard University assistant communications professor and author of Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City (Duke University Press, 2012). Go-go promoters had already moved to more digital advertising strategies when Hopkinson started to do the bulk of her research in the early 2000s, but looking over listings in the Washington Post and the alt-weekly City Paper for the 1980s and '90s proved frustrating. Those newspapers "never got their go-go listings right," she says. "It was not a priority to the go-go community to get to the City Paper audience. They've always had their own ways of getting the word out."

Instead, promoters relied on local radio and posters put up around Washington neighborhoods. "Stations like WPGC and some of the other stations that were in town were broadcasting go-go, and they would announce when the shows would be," says Kip Lornell, a George Washington University adjunct professor of music who co-wrote the first go-go book, The Beat! Go-Go Music from Washington, D.C. (University Press of Mississippi, 2009), with longtime go-go producer, manager, and activist Charles C. Stephenson Jr. Advertising parties was "really a tri-part effort for somebody who was going to be promoting go-go shows in the 1970s and '80s. You wanted it on the radio, you wanted to get it in print, but you sure as heck wanted those Globe posters all around town, too."

Globe posters became so identified with go-go that Washington native, poet, and photographer Thomas Sayer Ellis' debut collection, The Maverick Room: Poems (Graywolf Press, 2005)—named after one of the now defunct go-go clubs—includes a poem dedicated to the company titled "Bright Moments." It opens: "All night long the capitol glows. The Day-Glo day all night long. Day-Glo makes the capitol glow makes the capitol glow just like the globe."

Derek Gray, a special collections archivist at Washington's Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, started the library's Chuck Brown/Go-Go Music Archives after Brown's death in 2012, and put a call out to the public to donate materials—business contacts, photos, news articles, videos, CDs, tapes, ticket stubs. He programs events throughout the year to bring awareness to the archives and he's starting a go-go oral history project. But he's had a hard time tracking down posters. "When a lot of folks got wind of what we were doing, they were coming in and seeing what we had, and they mainly asked about the posters," Gray says. "I just could not locate any. I mean, we have three or four, and that came from one or two people."

Both Gray and Hopkinson say they know of a few people who have cherished Globe go-go poster collections, but they're not giving them up. That makes it difficult for the general public to access them. Gray says that last fall he was given a digital file with about 50 images of Globe go-go posters, which was added to the library's collection.

Of the 8,500 posters in the Globe archive, 1,117 of them are for go-go shows. This collection represents a mammoth trove of information that doesn't exist anyplace else. "These posters become a record of a culture and an activity that otherwise might not have been captured in this sort of material way," Hopkinson says, and her researcher's brain starts rattling off all the information she'd like to put together from the posters. "I would absolutely be interested in going through a big find like this collection, just to make a list of all the [go-go] venues. I'd like to see a map of those venues and where they were. A list of all the bands. So many go-go bands pop up, live, die, it could happen in a week. There's so many people that have come around and kind of gone over the years."

"People talk about how much go-go broadcasting was done, especially a lot of the big bands of the day, but radio broadcasts from the 1970s aren't archived anywhere," Lornell says. "The Globe posters cement who is actually playing where and give you very specific information that's really hard to get elsewhere." It's especially difficult to get a sense of geography because the neighborhoods where go-go clubs and events took place in the 1970s, '80s, and '90s have been gentrified, pushing go-go parties out into the surrounding Maryland counties in the early 2000s. Simply gaining an understanding of what bands played where and when "would help to give a clearer picture of what life was like in the 1980s that was so difficult economically and politically for communities of color, but so rich culturally," Hopkinson says, adding that because the music never really traveled beyond the region, its cultural and economic impact was an entirely local phenomenon. "In terms of go-go research, this is a significant development. The posters are part of the whole creative economy of the music. Go-go is so many things, and one of the most fascinating things is that it is a series of locally operated mom and pop businesses. This is one of the subversive parts of the music. It went a totally different direction than hip-hop that is nationalized and corporatized in most of its production processes."

"We now have one of the definitive go-go archives in the country just by virtue of having the Globe collection," Steele says. "That's one of the things that really excited me about this collection. Yes, there are really important stories about the history of mainstream music genres in Globe's archive, but there are just tons of little stories related to subcultures. Burlesque, wrestling, go-go, hell-raiser [drag racing] drivers, all this stuff is really interesting. But the go-go story, to me, is one of the ones that's most interesting mainly because that story is not really well-known. I like the idea that we can play a role in helping to spread the word about this really important cultural art form."

Organizing the Globe archive is the first step in doing that. MICA owns the Globe Collection and Press, and the Sheridan Libraries will be the custodial stewards of the business records and poster collection in its high-density, climate-controlled shelving facility. Next up: waiting to hear back about a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to digitize the collection, which the Johns Hopkins–MICA partnership applied for last fall. "There are a lot of superlatives associated with Globe," Steele says. "It was the largest collection and most complex collection I've ever overseen the processing of. If we get this [NEH] grant, it'll be the largest and most complex collection that we've ever digitized. We've always had a vision of making this material accessible to people online."

Pryor-Trusty, for one, knows an audience for this collection exists. "I would love to see a building, a place, where every last one of those posters is displayed, where people can travel from all over and see them. They had that certain signature. You could walk anywhere, drive by anywhere, and you could look at them and say, 'That's Globe.' They have to be preserved because they really are history."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged music, sheridan libraries