Here's a new fish story. One day two years ago, Ralph Etienne-Cummings found himself somewhere on the Chesapeake Bay staring at little blips on his sonar fish finder. A school of something had gathered under his boat. Rather than instinctively reach for rod and reel and cast his line in the water, he mused on the possibility of a more surgical approach to landing a big one. "What if I could use this sonar device to guide my lure right into the school—maybe even pick out the fish I wanted—and see when [the lure] gets eaten?" asks Etienne-Cummings, a professor of computer and electrical engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering and a devoted angler.

The problem, he knew, was that lures won't show up on standard finders. These devices fire ultra-sound pulses through the water via a transducer. When the pulse strikes something, like a large fish, school of fish, or the seabed, an echo signal bounces back, and the device constructs an image. The smaller the fish, however, the fainter the signal, to the point where it can't be detected. He'd need to find a way to make a typical plastic fishing lure, even one only 5 centimeters long, visible at a considerable depth.

Image caption: Ralph Etienne-Cummings

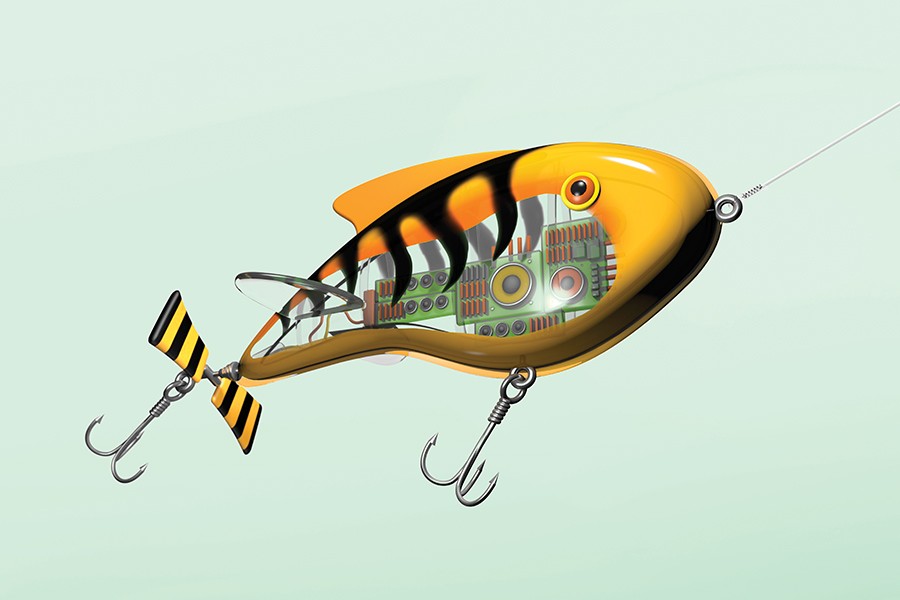

The solution: make it shout. He conceptualized a lure with a microphone, microprocessor, and other onboard tech that could respond to the pulses coming from a commercial fish finder. When it's pinged with a pulse, it emits a unique signal with an encoded message that can be picked up by the sonar's transducer and displayed as something more than a tiny dot. Imagine an arrow or the words "your lure is here." With the lure now visible, the angler can direct it to any fish blip on the screen. Etienne-Cummings likened the concept to an echo-based medical device he's working on to find millimeter-sized catheters not visible in standard ultrasound images, particularly when buried deep in tissue.

The prototype lure could contain other sensors to register water temperature, current flow, and even the size of the fish that's swallowed it. When surrounded by a solid mass, like the fish's mouth, the lure will immediately ping that it's no longer in free water. He envisions a later version of the prototype to feature a spring-loaded hook that can retract, letting the fish literally off the hook if deemed too small. Fishing with a friend? No problem. Each lure will have a unique ID.

Etienne-Cummings and a colleague, Emad M. Boctor, a Johns Hopkins assistant professor of radiology in the School of Medicine, have received a patent for this active echo fishing lure and will continue to work on the prototype this fall. Using such a smart lure might seem unfair, akin to fishing for dummies, but Etienne-Cummings defends his invention. "As a fisherman, I love the sporting aspect. I also love to catch fish. This increases my odds."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged computer engineering, electrical engineering, fishing