In the 1700s, Baltimore residents complained about the pigs. There were "pigs wandering through the streets making a mess of things," says Matthew Crenson, A&S '63. And the mayor and City Council couldn't do anything about it.

Image caption: Matthew Crenson

Image credit: Homewood Photography

The way the 1729 city charter was written, city officials had little means to create or enact laws. Nor could they raise funds to pay people to enforce those laws that they couldn't create. To do anything, the city had to ask the state for help. "So Annapolis passed this ordinance that says [residents] have to keep their pigs penned in," Crenson says, "but there was nobody to enforce it because the commissioners all had day jobs." The city's elites ended up building fences around the early city limits to keep the pigs out.

Crenson came across this gem during the five years he spent reading through early official records in the Baltimore City Archives for Baltimore: A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press), his detailed and engaging new book that takes a long view of how and why Baltimore's political systems work—or don't—the way they do. One of the book's main themes is the city's subservience to the state, a relationship Crenson argues is built into how Baltimore's government developed.

"People with money ran things because their money was needed, not just for the growth of the local economy but for the basic infrastructure of the town," says Crenson, a professor emeritus in the Krieger School's Department of Political Science. A city government created after the state meant that Baltimore was politically underdeveloped at inception, and "these seeds that get planted at the very beginning of the city's history develop over time and have consequences and establish patterns."

Crenson says these recurrences extend to how the city avoids addressing race. The city's business—and, therefore, governing—class had economic fingers throughout colonial enterprises, and, as Crenson writes in the book, for the sake of business, "conflict avoidance has been an enduring motif in Baltimore's engagement with slavery and race."

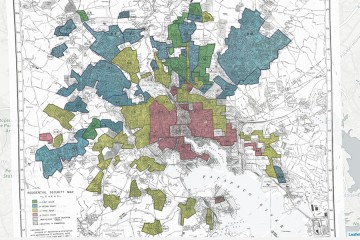

"It's one of the least highlighted issues" in the historical records, Crenson says, while pointing out that race is "also the city's biggest issue." Baltimore convincingly connects early Baltimore business attitudes toward slavery to the 1910 city ordinance that segregated neighborhoods. The mayor who signed the ordinance was J. Barry Mahool, an ostensibly progressive Democrat. He was in favor of women's suffrage, the eight-hour workday and a minimum wage, and regulation of city utilities. But when it came to race, conflict was to be avoided, which is built into the ordinance's title: "An ordinance for preserving peace, preventing conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in Baltimore City and promoting the general welfare of the city by providing so far as practicable for the use of separate blocks by white and colored people for residences, churches, and schools." As Crenson writes, city officials "were making an issue of race, in other words, to avoid the interracial friction that might compel them to address the issue of race." In 1917, the Supreme Court ruled such racial zoning unconstitutional, but the ordinance helped lay the groundwork for the neighborhood covenants and redlining practices that kept Baltimore racially and economically segregated over the 20th century and into the 21st.

Also see

Baltimore: A Political History brings a career's worth of political science research and a native son's insidery wonkiness to thinking about the political economy of Crenson's hometown. As a Johns Hopkins undergraduate, he met local Democratic fixer Vincent "Murph" Lanasa, who introduced the future political scientist to street-level party politics. Crenson returned to Homewood in 1969 to join the Political Science Department, where he taught for 38 years before retiring in 2007. His scholarly work, such as the 1983 book Neighborhood Politics, is rooted in fieldwork conducted in urban communities, including Baltimore.

Throughout Baltimore, Crenson points out how the city's deference to the state and avoidance of race recur through its history. At times, Baltimoreans expressed their displeasure—a number of 19th-century riots earned the city its "Mobtown" nickname—and forced local officials to deal with situations.

If they could, that is. Those fences built to keep the pigs out? Come winter, "Baltimoreans stole the fence posts for firewood and the commissioners decided they're gonna sue these guys for damages," Crenson says, adding that two of the thieves were the St. Paul's Church rector and the town's physician. Thing was, the city's charter didn't grant the city the legal authority to sue. "So they say, The hell with it. We'll let the pigs stay."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged political science, history of baltimore, baltimore city