Elisabeth Gilman was 62 years old when she heeded her party's call to run for governor of Maryland. She was the first woman ever to campaign for the state's highest office. The year was 1930. As she criss-crossed the state that fall, she promoted a socialist platform that championed working class families, the elderly, and the needy, with points of action that seemed radical at the time—establishing a minimum wage, a pension system, and a five-day workweek. "The Socialist Party wishes to make the world a better place for everyone to live in" was her tireless message. It was one she had honed after spending the summer in Europe, where she'd met with Socialist and Labor leaders in England, Germany, and Switzerland. There she'd aimed to learn information that would give Marylanders a better understanding of socialism and "something more than hot air."

She had also sneaked in vocal lessons with famous Viennese voice coach Hugo Stern. Upon her return, the 5-foot-tall "Miss Lizzie," as she'd fondly become known by the press, joked with reporters that she'd taken exercises to "develop chest notes" so her voice would have greater resonance. She added with a laugh, "Now I speak bass and will have ample opportunity to practice my new tones this fall."

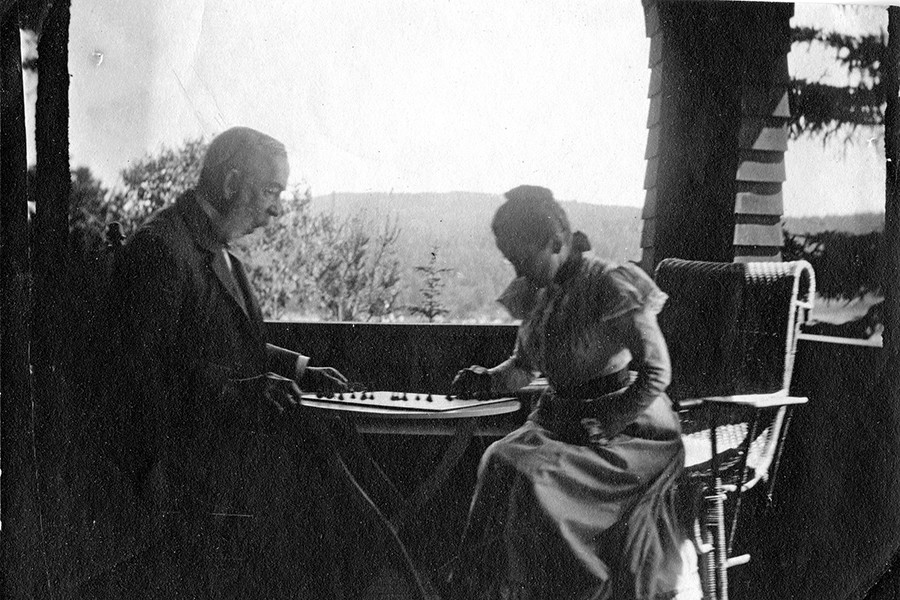

Image caption: At a point in life when most women of her station would have quietly withdrawn to private pursuits, Gilman was just getting started

Image credit: Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

Her gubernatorial battle was quixotic: She ran against Maryland's popular sitting governor, Democrat Albert Ritchie, and the Republican candidate, Baltimore's Mayor William F. Broening. But Gilman attracted a receptive audience wherever she spoke, unabashedly painting her opponents as pawns of big business and industry. At a rally before an African-American crowd at the Elks Hall in downtown Baltimore, she decried conditions in the state's penitentiary. Despite Governor Ritchie's claims that a recent survey gave high marks to the prison, Gilman noted, "Morale is poor and the plant one of the worst in the East." In rural Frederick, she told an assembly of several hundred that with her campaign, "the foundation is being laid for the future when the farmer and laborer will come into their own."

Gilman concluded her campaign the night before Election Day with an open-air rally at the corner of Broadway and Baltimore Street, followed by a torchlight automobile procession that wound through the city. When the votes were counted the next day, to no one's surprise Gilman had lost. What was surprising was the relatively large number of votes—some 4,178—that she received from her fellow Marylanders. "That was almost twice as many as the Socialist candidate for governor two years earlier," notes Ross Jones, A&S '53, who has spent nearly a decade researching and writing about the life of Elisabeth, the youngest daughter of Johns Hopkins University's founding president, Daniel Coit Gilman. Jones' book on Miss Lizzie is due out later this year from Secant Publishing.

"Elisabeth was a realist; she knew she would never get the votes she needed to win," Jones says. "But she wanted a pulpit from which to promote the progressive causes that had become her guiding light." At a point in life when most women of her station would have quietly withdrawn to private pursuits, Jones notes, Gilman was just getting started. Over the next 15 years, the firebrand with the pince-nez would go on to run for U.S. Senate, mayor of Baltimore, and even city sheriff.

"If you ask anyone in Baltimore today, 'Do you know who Elisabeth Gilman was?' most people say, 'Elisabeth who?'" says Jones. But he discovered a woman who had been a fixture on Maryland's political stage for more than three decades. By the time she died in 1950, just a few days before her 83rd birthday, he says, "Elisabeth Gilman had become one of Baltimore's best known and beloved citizens."

Jones' own ties to Johns Hopkins run deep. Retired since 1998, he spent more than four decades serving six of the university's presidents, most of that time as vice president and secretary to the board of trustees. An undergraduate history major who earned a graduate degree in journalism from Columbia University and started his career with the Associated Press, Jones has always been fascinated by Johns Hopkins people and events. He was doing some research in the archives about 10 years ago when he came across Elisabeth Gilman's papers. "I was captivated," he says.

Poring over her diaries, travel journals, and newspaper clippings as well as an informal memoir, Jones read accounts of young Lizzie's journey up the Nile River with her family, and of donkey rides across the deserts of Egypt with her father. Of her visits as a teenager to the West End docks in London, where she talked with prominent advocates for the working poor. Of the years she spent in France during World War I, leading a canteen for U.S. servicemen, and of her complicated relationship with a charismatic Episcopal priest whose work she bankrolled for nearly 25 years.

The more Jones read, the more he wanted to read. He quickly developed a routine. Several days each week he'd arrive at Special Collections in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library just as the doors opened in the morning. He'd pass several hours reading and making notes, take a quick break for lunch, and then return for another hour or two of research. "Reading Elisabeth's diaries and her letters, particularly those to her sister Alice, really brought her alive to me. I really came to know her," says Jones. He says he discovered a woman who had been the "apple of her father's eye," who grew into "a take-charge person who was decades ahead of her time—and who didn't take no for an answer."

The more he learned about Gilman and her advocacy, the more Jones became convinced that her work is especially relevant now. "It's really remarkable how so many of the issues she advocated for so passionately in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s are issues we're still grappling with in 2017."

As sturdy and energetic as she was as an adult, little Lizzie almost didn't make it through childhood. "All my activity is paralyzed by the sudden and alarming illness of our dear little child, four years of age, who has been the joy of our household these last sad years," wrote Daniel Coit Gilman to longtime friend Andrew White, then president of Cornell, in the spring of 1871. Her loss would have been a particularly devastating blow for Daniel, Jones notes, as just two years earlier he had suffered the death of his young wife, Mary, leaving him a widower and Lizzie and her older sister, Alice, without a mother.

Fortunately, by the end of that anxious summer, she had made a full recovery (from what later was identified as a form of meningitis). Not long afterward, Daniel Gilman accepted an invitation to become president of the newly established University of California. With his sister, Louisa, along to help with the girls, he moved his family from Yale, where he was professor of physical geography, out to the West Coast.

But the Gilman family's time in California was short-lived. In late 1874, the trustees of the estate of wealthy merchant Johns Hopkins approached Gilman with an opportunity too good to pass up: to create a new institution of higher learning—unlike any that existed at the time—as the founding president of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Lizzie was 8 when her family moved to Baltimore. The city would remain her home for the rest of her life. As youngsters, she and Alice received much of their education at home on West Saratoga Street, with a private tutor. "But Lizzie was also exposed to her father's colleagues from Johns Hopkins and to visiting scholars at a very young age. She sat in on dinners with many of the great intellects of the day, and she wasn't afraid to engage with them," says Jones. "They really took a shine to her."

Daniel Gilman recognized in his daughter a broad intellect—and a passion for the social justice issues that he held dear—and he took every opportunity to nurture those interests, Jones says.

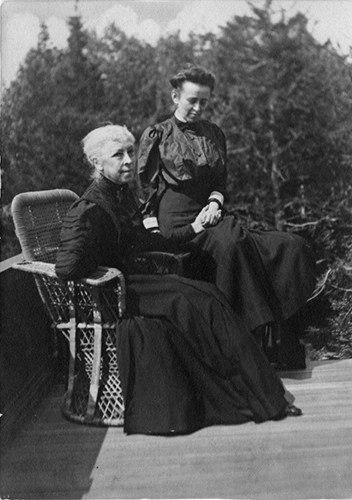

Image caption: At right is Elisabeth Gilman, age 42, with Lilly Gilman, her father's second wife.

Image credit: Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

In 1877, when Lizzie was 11, Gilman married again, to Lilly Woolsey. The girls quickly came to love their new mother, and in the years to come, Jones says, the family fell into a pattern. While Papa and Lizzie strolled the cities of Europe, climbed the hill towns of Italy, and investigated cathedrals, Lilly and Alice often hung back together at the hotel or pursued something less strenuous. "Travel opened up the world to Lizzie," says Jones. All of a sudden, everything she'd read about in her textbooks—art, architecture, culture, religion—was playing out before her in living color. "These travels with her parents made a lasting impact," says Jones.

It was on one such trip, when Elisabeth was 15, that Daniel introduced her to Father Charles Fuge Lowder, an Anglican priest who had established a mission church to serve those working and living along the teeming docks of East London. Inspired by the work of him and others—including social activist Jane Addams and her effort in 1889 to establish Hull House for newly arrived immigrants—she began working in her 20s to better the lot of the poor in Baltimore. As a "friendly visitor," a precursor to today's social worker, she moved across the city, visiting families in need of assistance and counseling. "She was as comfortable in the homes of Baltimore's middle- and lower-income families as she was in the homes of Johns Hopkins faculty members," says Jones.

In his book, he describes Gilman's efforts to establish boys' clubs for the "'toughs and roughs,' as they called themselves,"—"to supplement what is lacking in their lives, to foster that which is good." She also created a "Community Workshop for the Unemployed," where men could earn $1 a day making bandages and simple furniture, and a "Night Bureau" for homeless people during the winter months. "Elisabeth Gilman had seen conditions in Baltimore and in London that few of her upper-class friends would ever see," writes Jones. "Those experiences strengthened her resolve to do whatever she could to help lift people out of their difficult and sometimes desperate circumstances."

Gilman never married. But in her late 40s, she did meet a man—and embrace a cause—that would alter the course of her life.

The transformative experience unfolded in October 1916 at a weeklong conference in leafy Sherwood Forest, outside Annapolis. Just a few months earlier, Gilman had been in Boston at a church institute that featured lectures by Wellesley College Professor Vida Scudder, a leading proponent of the Social Gospel Movement. Scudder's message—that Christians are called to fix the ills of society by applying the biblical principles of charity and justice—had struck a chord with Gilman, a lifelong faithful Episcopalian, Jones notes.

Gilman was primed, then, when she got to Sherwood Forest and discovered a group of men and women who saw the world as she did. The gathering of 200 people featured the leaders of the socialist movement in America—including Walter Rauschenbusch, John Spargo, Harry Laidler, and Mercer Green Johnston—who led provocative discussions on poverty, racism, child welfare, and women's rights. Gilman was swept up. "I could not ignore their pleas for social justice," she wrote in her informal memoir.

She was most struck by the fiery rhetoric of Johnston, a militant clergyman who'd been ousted from his post in New Jersey by the Anglican Church for being too progressive. "From the moment she met Mercer Green Johnston, Elisabeth was smitten—smitten by his confident personality, his rhetoric, his unflagging commitment to advance the cause of the Social Gospel, his courage and determination in the face of obstacles, and, later, his bravery in battle," writes Jones.

The relationship that developed between Gilman and Johnston over the next 30-plus years was a complicated one—and despite an intense start ("they were kindred souls," Jones says), it didn't end well.

In order to get a fuller picture, Jones expanded the scope of his research from the Johns Hopkins archives to the Library of Congress, where Johnston's papers are held. Based on his reading of the correspondence between the two, and Elisabeth's letters to Alice, Jones believes that Gilman may have harbored romantic feelings for the larger-than-life Johnston. "Early in their relationship, despite the fact that she knew he was married, she may have misinterpreted his expressions of affection toward her," writes Jones. Soon after the Sherwood Forest meeting, Gilman opened a bank account for Johnston with a $1,000 deposit (about $22,600 in today's currency) and assigned a life insurance policy to him and his wife, Katherine, "as a token of the friendship and of my sympathy with their work in behalf of the Kingdom of Christ." Says Jones, "This all happened very quickly at the end of 1916. Elisabeth was clearly very disappointed that Mercer no longer had a job—and a pulpit from which to preach the principles of Christian social justice. She had the resources to help him financially, so she jumped right in."

A few months later, in April 1917, when the United States entered the Great War in Europe, Johnston encouraged Gilman to follow him and Katherine to France. There they would provide aid to U.S. servicemen through work with the YMCA. Though Gilman had known the couple for only a short time, she was willing to uproot her comfortable existence. Now 49, with both her parents gone (Daniel Coit Gilman died in 1908, Lilly in 1910), she was "eager to toss aside the routines of her life and follow this creative, energetic proponent of the Social Gospel," writes Jones.

During the ensuing two years in France—documented in powerful detail in letters home to Alice and regular dispatches in the Baltimore News and Baltimore American—Gilman assumed leadership of a large canteen in Paris. It was a place of respite where 300 to 400 weary U.S. soldiers could take temporary leave from the horrors of the battlefield.

For Gilman, the work was exhausting, rewarding, and dangerous. Though bombs exploded nearby during nighttime air raids, she wrote to Alice, "The sounds of war ... do not trouble me personally. I have decided to go on quietly with my work, and not let my sleep be interfered with more than possible, and so go to bed, instead of to the clear [shelter] when there is a raid."

For most of their time in France, Katherine Johnston lived and worked with Gilman, while Mercer's efforts took him closer to the dangerous front lines. "It was Elisabeth's hope at the start that they would all live together in Paris, where Mercer would volunteer as an ambulance driver. But shortly after they arrived, the Army took over the ambulance service and ruled that he was too old," Jones explains. "So Mercer volunteered with a YMCA center that was situated right on the front lines with the troops." Gilman worried about him in her letters home, and with good reason. "We heard tonight that Mr. Johnston has been gassed, but he wrote the telegram himself so it is not alarming, though very bad," she wrote to Alice in November 1918. The war would end just two weeks later.

Johnston returned home a hero, notes Jones, with a Distinguished Service Cross and a Croix de Guerre from the French government—and no steady source of income. Gilman came back to Baltimore ready to take up the socialist agenda she'd embraced so passionately two years earlier. Almost immediately she resumed her financial patronage of her dear friend—"to free him to work untrammeled for God's Kingdom on Earth," as she wrote to her attorney. She bought a house on Holmes Avenue in Baltimore, where Mercer and Katherine could live for a nominal rent, and hosted an Episcopalian blessing of the new home. "There were these emotional overtones to the whole business," says Jones. "It almost seemed like a blessing of the trio and their togetherness."

Gilman also invested in a magazine Johnston was eager to start, and established the One Big Brotherhood Fund, which, Jones writes, "was a device to support Mercer and Katherine so that he could devote himself to speaking and writing, two things Elisabeth constantly urged him to do." Johnston and Gilman also established the Christian Social Justice Fund, to support "educational and religious organizations whose programs are concerned primarily with economic and social reform."

Ultimately, Gilman's generous financial backing was the lightning rod for the demise of their friendship, Jones says. Over the years, Johnston began to chafe at the strings he perceived to be attached to her funding, and to complain when Gilman demurred from supporting what he considered to be important projects, notably the People's Legislative Service, which he led in Washington, D.C. "I think part of what occurred was that she became a little too overbearing for him—maybe a little too controlling," says Jones. "He was not a flexible person and Elisabeth wasn't either."

Ever the pragmatist, Gilman did not let the emotional ups and downs of her relationship with Mercer Johnston derail her from pursuing her socialist agenda throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Jones says.

Among other projects, she launched the Maryland chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and led a national effort to raise funds for the destitute families of the 1922 West Virginia miners' strike. She appeared before the House Immigration Committee in March 1926 to criticize congressional plans to register aliens and to extend provisions of the existing deportation law, and took part in a national conference that discussed forming a permanent organization to work for old-age pensions (the precursor of Social Security).

She also organized a dinner to honor the editor of The Nation, Oswald Garrison Villard, on the liberal weekly's 10th anniversary, in March 1928. The plan was to hold the event at a downtown hotel. "But no hotel in Baltimore would permit its dining facilities to be used by a group that would include Negroes ... [and the] invitation list had included a small number of the city's African-American population," writes Jones. So Gilman stepped up to host the event at her own home at 513 Park Avenue. The resulting Sun headline: "Banquet in Honor of Editor to Be Held at Private House After Dispute Caused by Seating of White and Negro Guests." Says Jones, "By crossing the color line, that dinner cost her friends among her upper-class social group, but she later told a reporter that she didn't mind—the sacrifice was worth it."

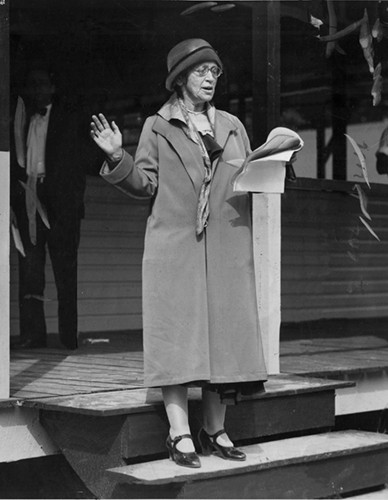

Image caption: Lizzie Gilman delivering a speech, location unknown

Image credit: Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

Many who visited Gilman came under the umbrella of the Open Forum. The weekly Sunday afternoon lecture series, which began just before World War I and lasted until the early days of World War II, drew more than 1,000 people almost every week. "Elisabeth was the driving force for the Open Forum, particularly in the later years," says Jones. Speakers included suffrage leader Harriot Stanton Blatch (daughter of American suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton); birth control advocate Margaret Sanger; and David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University and an ardent pacifist.

In 1930, Gilman's socialist advocacy took a political turn when she accepted the Socialist Party's nomination to run for Maryland's governor. Telegrams of congratulations poured in from around the country on the announcement of her nomination. Jones even found one from prominent muckraker and writer Upton Sinclair. Writing from California, Sinclair had pasted a newspaper clipping with the demeaning headline "Socialists Back Girl in Maryland" on a piece of stationery, and scrawled beneath it: "Hello, Girlie."

Sparked by the mass discontent that had spread across the country with the onset of the Great Depression, "the Socialist Party got a temporary life in the period just before Elisabeth mounted her campaign for governor," says Jones, who includes a chapter in his book that charts the rise and wane of the movement. "Though she knew she wouldn't win, she saw it as a way to educate the public and to keep the imperatives of the Social Gospel in front of people."

Undaunted by her defeat that late fall of 1930, Gilman went on to mount several more political campaigns over the next 15 years—for U.S. senator in 1934, mayor of Baltimore in 1935, senator again in 1938, and then for sheriff of Baltimore in 1942.

She'd become a darling of the local press, whose editors had been covering her causes—and publishing her letters—for years. Noting that "Miss Lizzie" was rarely seen around town without one or two of her beloved pet chows in tow, Jones says, "She was a character, and her style and intellect appealed to journalists."

Hundreds of Gilman's admirers from Baltimore and around the country turned out in November 1941 for a testimonial dinner in her honor at the Southern Hotel. One of them was Sidney Hollander, a Johns Hopkins economics professor, who nicely summarized her far-reaching vision and impact, Jones writes in his book. Hollander called Gilman "one of America's grandest institutions," and noted, "She has stirred Baltimore as Einstein stirred the universe."

Gilman remained "tough as a pine knot," in the words of a surgeon friend, until her death on December 14, 1950, at the age of 82. Jones found long obituaries in the Baltimore newspapers and The New York Times, among other papers, but says the editors at the Evening Sun may have summed up Elisabeth Gilman's life best. "She had the ability to prod people—usually agreeably—into thinking and rethinking, even when they concluded that her position on whatever cause she was currently espousing was a mistaken one," they wrote, and concluded, "Even those who took issue with her most strongly will realize that Baltimore has lost a personality and link with the calmer and more spacious past."

Given Elisabeth Gilman's pioneering efforts, and the impact she had on Baltimore—and across Maryland and even the nation—is it surprising that she's gone overlooked by historians? Jones has given this ample thought over the 10 years he's worked so closely with Gilman's papers. He has concluded that a variety of factors combined to make her mostly a footnote in history.

"She didn't have big-city clout, as Jane Addams did in Chicago and Vida Scudder in Boston," he says. "Also, she didn't write books or for journals and magazines as the two of them did, and therefore she didn't develop a national platform to spread her ideas. Moreover, she was not an educator and she lacked the serious academic credentials that Scudder had."

And, true to her roots in the Social Gospel, Gilman was never someone driven by ego. "Elisabeth was a worker bee," Jones says. "Yes, she was out front with her campaigns and the Open Forum, but I think she found a lot of satisfaction in organizing support for causes, handling all the logistics, the promotions and solicitations.

"For Miss Lizzie, it wasn't as much about her as it was about getting the job done."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged sheridan libraries, baltimore city, johns hopkins history