Sir Isaac Pitman used the term "phonography" for the system of shorthand he invented in the 1830s. The word embodied what the Pitman system was meant to enable: "writing the voice." During a recent Skype video conversation with the classicist Shane Butler, I hold up a copy of The Manual of Phonography, a book by Isaac's brother, Benjamin, and a bemused Butler replies, "I can best you on that. I've actually been to the house in Bath, England, where Isaac Pitman lived." Then Butler apologizes. "I have a cold, which has ruined my voice, which is ironic."

Image credit: Paul Garland

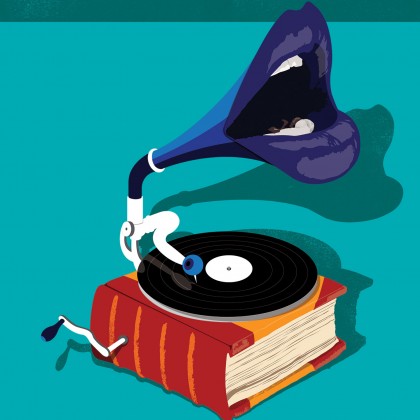

Ironic because our conversation is all about voice. Butler, a professor in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences' Department of Classics, has a deep interest in the voices he hears when he reads classical texts, and the relationship of text to voice. He recently published The Ancient Phonograph (Zone Books, 2015), which he describes in its introduction as "a new book about a very old subject: the role of sound in Greek and Latin literature." Classical texts were "phonographic literature" and "a noisy business," he writes, and he ponders the purpose of whoever first committed Homer to the page. Was it to record the details of Homer's stories, the sense of The Iliad and The Odyssey, or the music of the poet's meter and alliteration, the sound of the epics?

Butler reads Philostratus' Lives of the Sophists and it becomes "a jukebox or, better still, a radio program." He notes the adjectives used to describe Nero's singing voice and playfully offers that the emperor was a "dusky-voiced torch-song singer." He says, "We think of antiquity as being dead and in museums, but because of its lack of definition and a lack of finality, it's also very alive, just as we are. You can't get to the bottom of it. You can't fully reconstruct it." But, he adds, that's a large part of what makes it real to us.

Part of his fascination is with the capture of a lived experience so it can be experienced again, whether through a classical text or vinyl record. "The voice moves you in moments that seem to be radically specific," he says. "The vocal performance is the thing that says, 'I'm unrepeatable. I'm here, you're here—isn't this amazing?' And yet we do capture that, and we listen to it over and over and over again. It's beautiful and crazy and fascinating to me."

Butler frequently invokes modern sound technology. The introduction of The Ancient Phonograph is titled "Liner Notes," and the five chapters are "Track 1," "Track 2," etc. In "Liner Notes" he writes, "Time now to start taking some (very) old records off the shelf. Our playlist will be an eclectic one, and I mostly have permitted myself simply to choose a few of my own personal favorites: top-forty hits from Cicero, Ovid, and the ancient tragedians, but also some rarer material from Sophistic declaimers, pseudo-Anacreon, and even the half-mad emperor Nero."

As a graduate student at Columbia, Butler made a close friend who appears in The Antique Phonograph as "the record collector." When this friend died, Butler was bequeathed his vinyl collection as well as his diary of the performances he'd witnessed at the Metropolitan Opera. He has kept the LPs and the treasured memories of voices heard. "We're all used to loss as much as we are to memory," he muses. "Things that we can remember but not well enough, the people who are dead that we knew. So, we have this strange, modulated relationship between presence and absence. The voice is a great example of that. Our whole body resonates with it. It's radically present. It's not an idea; it's a thing. It's right in front of you, talking to you, resonating in your own body. And yet, it's gone, right? It's temporary. So, it's radically present and radically evanescent at the same time. That's really beautiful."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged phonography, voice, department of classics