Businessmen love Jay-Z. Specifically, they love one line the rapper-turned-business-owner says in Kanye West's 2005 single, "Diamonds From Sierra Leone (Remix)": "I'm not a businessman, I'm a business, man." Jay-Z's declaration that he's not merely an earner in the music industry but a brand all to himself became the lead sentence in a Forbes piece titled "10 Startup Tips from Hip-Hop Lyrics," which pointed out that Silicon Valley venture capitalist Ben Horowitz uses rap lyrics to teach business lessons. In a different Forbes piece, entrepreneur, best-selling author, and ViSalus Sciences CEO Ryan Blair used Jay-Z, and that lyric specifically, as a signpost guiding his own evolution from a "suit-wearing, briefcase-carrying businessman" to "creating a brand in business unique to myself." Being a business, man: You're not just making your way—every move you make puts money in the bank.

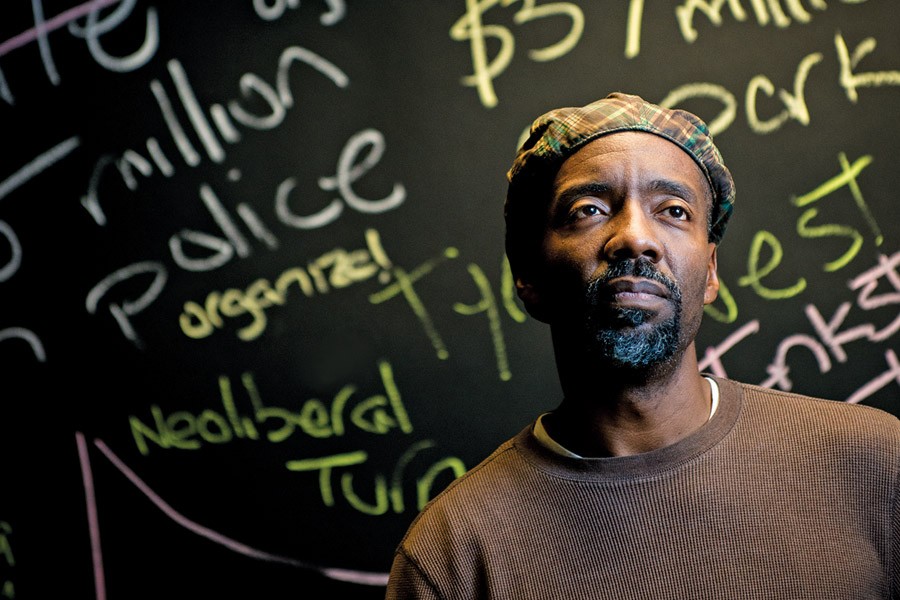

Lester Spence hears that entrepreneurial swagger in the lyric as well. What the Johns Hopkins associate professor of political science and Africana studies sees that line as representing, though, is more complex than a simple rags-to-riches tale of success in free-market American capitalism. For him, the lyric is a distinct comment on black labor today. Rappers, as hip-hop fans know, regularly boast about how constantly they have to work to make ends meet. Their songs are often tales of street entrepreneurs working in underground economies, sure, but the songs extol getting paid by any means necessary. They produce so everybody else—the kids and loved ones they're supporting, the fans who are listening—can consume.

Spence sees such tales of "hustling," as the day-to-day grind is known in hip-hop, as an echo of African-American work songs, which were sung by men tethered by slavery or prison to hard labor. While the iron chains of the eras that produced those songs are gone, hip-hop's hustler wears a metaphorical chain of his own making. He hustles just to get by, the way so many people do today.

As Spence notes in his recently published book, Knocking the Hustle (Punctum), from the early 1970s to the present, American labor productivity has increased 80 percent while wages have stayed stagnant or declined. That we work more to earn as much as we once did—or even less—is a standard woe of the American economy in 2015. How these hip-hop celebrations of the hustler function in African-American communities, though, is what Spence finds disconcerting. Hustling is embraced as the appropriate adaptation to living in today's economy. The individual's having to learn whatever it takes to get by is a virtue in today's economy. Anybody who isn't constantly looking for ways to improve the return on his personal human capital simply isn't hustling enough. And for those people who are too lazy to maintain a level of at least subsistence hustle? Their failures and their poverty are a cul-de-sac of their own making. The black church will tell them that. Black elected officials and business elites will tell them that. Hell, Jay-Z himself will tell people that. In his song "Can't Knock the Hustle," he sneers at day-job drones who only work 9 to 5, "lunching, punching the clock."

The ideas represented in the "I'm a business, man" lyric strike Spence as an instance of popular culture reproducing a political idea and story: Successful people work hard and get ahead by investing in their human capital, and people who aren't successful simply aren't working hard enough to do that. Recall President Barack Obama on the 2014 midterm elections campaign stump, lamenting that "if Uncle Jethro would get off the couch and stop watching SportsCenter and go register some folks and go to the polls, we might have a different kind of politics." In other words: The problem with black people is not that the economic and political infrastructure has anything wrong with it, but that they're not doing enough for themselves.

That there are gaps—in education, in wealth, in political power—between blacks and whites isn't what Spence is zeroing in on. Those gaps have been well-documented and studied. Black unemployment remains twice as high as white unemployment. Economic disparity between whites and blacks widened during the recent recession. Racism is real, and it continues to segregate cities, schools, and the workforce today. It fuels practices such as redlining housing policies, voter suppression, and mass incarceration. But what racism doesn't account for are the political ideas and policies that reproduce similar economic and political power disparities within African-American communities. Racism doesn't account for black elected officials who embrace the same economic policies that adversely impact black populations. Racism doesn't account for the belief among black leaders that the onus for improving the lives of black people falls not on addressing inequities built into economic, educational, and social infrastructures, but on addressing shortcomings in African-Americans' character.

For Spence, the ways in which black politics has been shaped by neoliberalism start to address how these inequalities have been reproduced within the black community over the past 40 years. The core of neoliberalism economic philosophy is the idea that society, and all of its organizations and institutions, works best when allowed to operate on free-market principles, free especially of government intervention. Neoliberalism, in the view of its advocates, produces a system that rewards enterprising people who improve the return on their human capital—the entrepreneurial hustlers. The period from the 1970s to the present witnessed the slow erosion of the domestic programs and policies enacted from the New Deal through the Great Society. When unemployment and inflation spiked during the economic crises of the 1970s, politicians and policymakers began following an economic model that insisted that a free market could fix what government regulation hampered. By the 1980s, neoliberal ideas were becoming entrenched: What was good for the economy was also good public policy.

Political scientists, economists, and pundits wrote about neoliberalism while political scientists wrote about racial politics. But much less was written about how neoliberalism and racial politics overlap. David Harvey's 2005 A Brief History of Neoliberalism explored how neoliberal economic policies evolved into political policy in Western democracies. Cornel West's 1993 best-seller Race Matters argued that conventional liberal/conservative American political discussion ignored the role race played in social and moral public discourse after the civil rights era. Each took the short, overview approach; neither focused specifically on how neoliberal economics had slowly invaded black politics over the past 40 years. With Hustle, subtitled Against the Neoliberal Turn in Black Politics, Spence has written that book.

It's a dense but readable hybrid of ambitious scholarship, partly touching on the histories of economics, urban policy, and education since the 1970s, and partly showing how those developments worked to narrow the point of view in black political discussions. Spence has brought together a wide web of research—everything from academic papers in economics, political science, and sociology to pop culture criticism and daily print and television journalism—to shape his argument. Hustle is Spence's attempt to write a book about what one could argue is a guiding force of our era, he says. He's written it for a general reader, hoping to speak directly to the people now living under neoliberalism's fallout, people who haven't seen the policies of the past 40 years, for instance, improve schools or their job prospects or the cities in which they live.

"Can I write a thing for black people that does some of the work that Race Matters did for previous generations?" he asks, adding that the devastation of poor and working-class black communities was caused by people, be they elected officials or thought leaders, implementing and embracing neoliberal policies and ideas. "When I'm thinking about who the reader is, I'm thinking about my dad. I'm thinking about my fraternity brothers. I'm thinking about people who can read this and see that there's this thing hanging over them in all these different ways, but it's the creation of human action. The neoliberal turn was the product of human action, again and again and again."

Hustle's most revelatory chapter focuses on black churches. And it's illuminating precisely for how Spence connects the content of "prosperity gospel," a variant of evangelical Christianity, to the political imaginations of churchgoers. Rarely do academics—or journalists for that matter—look at what is presented in churches as political content, outside of how churchgoers impact elections. (For example, the emergence of the Christian right as a voting block in the 1970s.) Spence argues that what is said in church from the pulpit represents a neoliberalization of the black church.

The chapter opens with a brief discussion of two New York Times articles from the Detroit area following the 2008 economic crash that hit the automotive industry and the region hard. One, "Detroit Churches Pray for 'God's Bailout,'" was a report from the Greater Grace Temple, one of Detroit's many churches that, at the time, held special services to help its congregations through a difficult time. Spence notes that in the photo that ran with the article, three white luxury SUVs shared the stage with the church's leader, Bishop Charles H. Ellis III. The article reported that the vehicles were on loan from local dealerships and that Bishop Ellis, "urged worshipers to combat the region's woes by mixing hope with faith in God." Spence sees the vehicles as having two symbolic values. For those who worked in the automotive industry, it was a symbol of what they depended on to survive. For those who didn't work making automobiles, the SUVs were status symbols, reminders of what they could have if they would only hustle harder.

The following year, another Times reporter visited Pontiac, about 30 miles outside Detroit, to write about the automotive industry's role in creating a black middle class in that area, and how the industry's collapse was decimating those families. Titled "GM, Detroit, and the Fall of the Black Middle Class," the article told its story through a profile of Marvin Powell, a longtime autoworker, one of the 600 who still worked making trucks at General Motors' Pontiac Assembly Center. Powell worked the only shift the plant maintained after getting rid of nearly two-thirds of its workforce through buyouts, early retirement, and layoffs.

During the reporting of the story, Powell learned that GM was planning on shutting down all of its factories for 10 weeks, which would leave him without his $900-per-week paycheck for that period. Powell said he might use the freed-up time to try and become a chef and start a catering company, adding that he had never intended to be a "GM lifer."

He attributed his positive outlook in trying circumstances to being a Greater Grace congregant, where he led a Sunday school class and was one of the church's armor bearers, an honorary position. His leadership role in Greater Grace had made him an esteemed figure at the auto plant, and his co-workers had encouraged him to run for a union leadership role. He demurred from that, but they sought him out for advice, nevertheless. What was he going to do when the plant closed? Powell told them that he couldn't control the plant's closing, so he didn't worry about it. He also said, "I tell them that God provides for his own, and I am one of his own."

That leapt out at Spence. Born and raised in Detroit as the son of a Ford autoworker, he was struck by Powell's resilience in the face of so much economic upheaval. But he was also taken aback by the way Powell conceptualized the situation. The autoworker didn't consider a union leadership position as providing him with an opportunity to fight for his and his co-workers' jobs. Instead, as Spence writes, "in Powell's opinion those who choose God will be saved from the worst of the economic crisis while those who don't, won't." Spence identifies this idea as part of the message spread by prosperity gospel, a doctrine that started in white churches in the 1950s and sprang to national attention through 1980s televangelism. It has taken strong root in black megachurches over the past two decades. Spence visited a black church in Baltimore County led by a charismatic prosperity gospel preacher who argued that everything associated with the economic crisis—debt, poverty, unemployment—was caused by a "poverty mindset." The minister reasoned that this mindset causes people to spend their money instead of saving it, causes "them to lay around when they should be hustling." And this mindset was the direct result of somebody having a bad relationship with God.

Spence writes: "Note the logic here. People are materially poor because they don't think right. Their inability to think right makes it impossible to receive God's blessings"—which can come in the form of spiritual or material reward. And the only way to right that bad personal relationship with God is for a person to change how he or she thinks—to improve their human capital through spiritual pursuits. These spiritual pursuits, it should be noted, often take the form of sermons and books that congregants can buy and workshops they can pay to attend, in addition to supporting the church by tithing.

For Spence, prosperity gospel, through prolific and celebrated pastors such as Creflo Dollar, founder of the mammoth World Changers Church International in Georgia, transforms "the Christian Bible into an economic self-help guide people can use to develop their human capital." It's a way to make questions about who lives comfortably and who lives in poverty a matter of which one spiritually deserves to do so. This notion, Spence writes, represents a neoliberalization of the black church—not only because the prosperity gospel frames the problem of poor people as a problem of those who do not improve their human capital (not as something wrong with the system in which they must live), but also in how the increasingly multi-millionaire leaders of black megachurches compete for their congregants' tithes and spiritual consumerism. Such a practice not only creates vast economic disparities between ministers and congregants—Spence notes an AtlantaBlackstar.com news website article that named eight black preachers who make more than 200 times what their churchgoers do—but it shapes parishioners' political imagination.

Fighting poverty, debt, and whatever economic adversity a congregant faces thus becomes only a spiritual matter for the individual, not the collective concern of a political organization. And getting people to see the political content in a church service is something Spence hopes readers will take away from the book. "What I want is for people to read it and see their world through new eyes," he says, adding that he hopes that by pointing out how prosperity gospel reproduces neoliberalism's disparities, readers might begin to seek other solutions to dealing with it.

There are possibilities for finding ways out of the neoliberal situation other than simply buying into the hustle, Spence says. Throughout the book, he offsets his charting of how neoliberalism seeped into black politics by citing contemporary instances of grassroots activism and political organizing to combat neoliberal advances. They may be modest, they may be temporary victories, but the examples he cites—the Urban Debate League that cultivates policy debate among city high school students; the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement that organizes communities to develop more equitable public policies; the Baltimore Algebra Project and Leaders of the Beautiful Struggle that in 2008 blocked Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley's attempt to spend $108 million in taxpayer money to build a new prison to house juveniles charged as adults—actively oppose the neoliberal turn in public policies.

Spence considers himself a product of such black activism. At 46, he's spent almost his entire life in majority-black cities. He was born and raised in the Detroit area; his father was a pipe fitter who worked for Ford Motor Company, his mom a substitute teacher. The Spence family lived in the predominantly black Inkster neighborhood until moving to the predominantly white suburb Redford in 1985 as economic depression hit the city, and he attended the University of Michigan in nearby Ann Arbor for both college and graduate school. But he didn't get into Michigan at first. It was only through the university's Summer Bridge Program, an introduction to collegiate life for incoming low-income freshmen and students of color, that he was able to enroll. That program was the result of black student activism on the school's campus. Between 1970 and 1987 African-American students repeatedly protested the university's practices and policies in three Black Action Movement protests, the second of which, in February 1975, led to the creation of the program that became Bridge.

"I would argue that the reason diversity is now important at Michigan is because of black student activism," Spence says. "It didn't work perfectly, but that's how politics works. It's not pretty. It's very long term. It's not sexy. It's not going to get you on TV. It's not going to get you any of that stuff. But it matters." And he's hoping Hustle's readers will take that message from the book. "When people write about neoliberalism, there's a tendency to make it seem like a fait accompli, that it's going to happen and there's nothing you can do to stop it," Spence says. "I wanted to make an aggressive assertion that political organizing matters."

To make such alternatives visible is why Spence decided to place Hustle with the open-access publisher Punctum. A print copy can be bought through Punctum's website, but the publisher is also making a digital version available free of charge six months after release. If Spence is going to advocate knocking the hustle, he might as well do it himself. If he's writing a book that argues against being one of the many entrepreneurial hustlers just looking to get paid, then he better not put an economic barrier in front of somebody wanting to access that idea.

"I believe in public action, to the extent that if we're going to problem-solve this world, our ability increases when we're able to see public examples," he says. "I mean, I can't live a perfect life, that's not possible. I, too, get caught up in the hustle. But at the very least I can write against that in ways that will inform not just the ideas and behaviors of people around me but also ways that can inform my own behavior. It can allow me to say, 'There's this other way to be—and you don't need to do this to yourself.'"

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged political science, lester spence, christianity, africana studies, neoliberalism, black politics