Earlier this year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement set up a display of 19 cultural artifacts that had been stolen from Italy and were about to be returned. There were a 17th-century cannon, a Byzantine gold pendant, three frescoes illegally excavated from Pompeii, a second-century bronze bust, and books, including a 1672 edition of Ferrante Imperato's Historia naturale…di minere, pietre pretiose, & altre curiosità (Natural history of minerals, precious stones, and other curiosities). That last item had been stolen from the Historical National Library of Agriculture in Rome and turned up in an unexpected place—in the Sheridan Libraries on the Homewood campus.

Before we go any further, no, no one from Johns Hopkins stole the book. And yes, there is a back story.

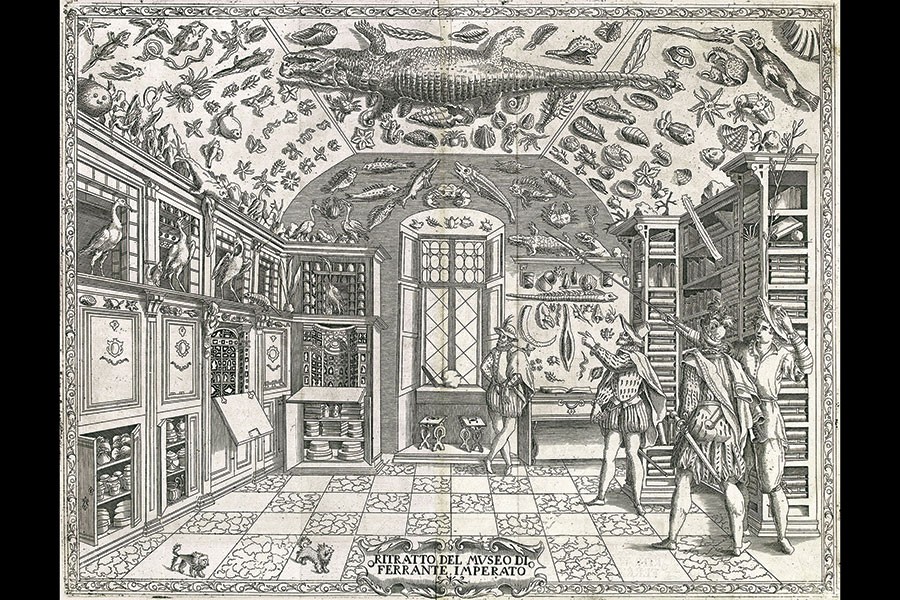

The Historia naturale, first published in 1599, was based, in part, on the contents of the author's vast specimen collection displayed at the Neapolitan Palazzo Gravina: a catalog of sorts of the vast natural history collection assembled by Ferrante Imperato, a wealthy apothecary who lived in Naples in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Imperato gathered specimens on his travels throughout southern Italy and developed an international reputation as one of Europe's foremost experimental scientists. He assembled examples of minerals, exotic medicinal plants, shells, coral, and sea creatures, and carefully organized them according to their elemental properties (earths, salts, fats, metals, fiery matter, etc.). He was among the first to establish that fossils were not inorganic earth objects but the actual remains of organic creatures.

Earle Havens, the curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Sheridan Libraries, says of catalogs like the Historia naturale, "People sometimes refer to these volumes as 'paper museums.'" Often they are all that remains. "The original museums almost never survive. The only place they survive is in books."

Havens knew about the Historia naturale, which is not only a beautiful book but has a remarkable engraving on its first pages—the oldest known image of a natural history museum. The Sheridan Libraries holds one of the world's most extensive collections of books that document the development of museums (including a 1599 copy of Historia naturale), and when Havens learned in late 2011 that a fine copy of the rare second edition of Imperato's volume had become available in the antiquarian book trade, he bought it for the Sheridan Libraries. The dealer, an established antiquarian bookseller who had done business with the Sheridan Libraries for years, had acquired the Historia naturale from an Italian auction house in Florence.

No one involved in the auction realized that the book had been purloined, probably not long before it was sold through the auctioneers, which is not unusual in the world of rare and unique books. The theft was not discovered and reported to Italian police until May 2013. Later that same year, the dealer called the Sheridan Libraries to inform Havens of the authorities' suspicion that the book had been stolen, and not long after that, an agent from ICE's Homeland Security Investigations arrived unannounced to claim it. As soon as Havens could verify that the copy of the book in the library's possession was indeed the pilfered volume described in official documents, Johns Hopkins arranged for its return. The dealer, who was not at fault (blame for insufficient diligence probably falls on the auction house, though the large majority of rare books have little or no evidence of former ownership), refunded the purchase price.

Havens was sorry to part with the book, but the tale has a happy ending. Not long after he gave back that copy of the Historia naturale, a better 1672 edition in deluxe condition—one of the finest copies in the world—came on the market and the library elected immediately to acquire it. In the Department of Special Collections in the Brody Learning Commons on the Homewood campus, Havens shows off this edition, of which only a handful are known to exist in such beautiful form: not as one bound book but two large volumes on heavy and expensive paper, in the original bindings, printed in red and black ink, with the all-important opening engraving untrimmed and so large it must be folded out to be fully seen and appreciated. The many other engravings in the book are superior to those of the copy that was stolen, too, for they are all early strikes of the plates, which wore down over time, making inferior impressions later in the print run. In all respects, it's a finer book than the one that had been filched from the Italian agricultural library. "I'm so relieved it worked out this way," Havens says. "Hopkins really lucked out."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged rare books