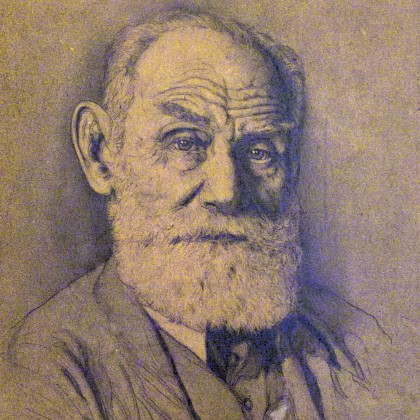

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, that giant of Soviet science, was supposed to be a priest. His father was. His father's father was an unordained clergyman in the rural town of Riazan in Central Russia, where Pavlov men had served the Eastern Orthodox Church going back to Peter the Great. But when Ivan, born in 1849 as the first of nine children, entered theological school in 1860, Russia and especially its younger generation were swept up in a reform-minded, modernizing bloom. In 1861, Tsar Alex?ander II emancipated Russia's serfs, an estimated 23 million people, and progressive intellectuals grappled with new developments in politics, phi?losophy, and science. After reading Russian translations of physiologist Claude Bernard's lec?tures and George Henry Lewes' Physiology of Common Life (1859), as well as Russian physiolo?gist Ivan Sechenov's Reflexes of the Brain (1863), Pavlov realized the seminary wasn't for him. For the rest of his long and rich life, he turned to sci?ence to understand the unseen processes of the body as a way of unlocking the secrets of the mind. Science would be his religion.

Image caption: Portrait of Ivan Pavlov by Ivan Streblov (1932).

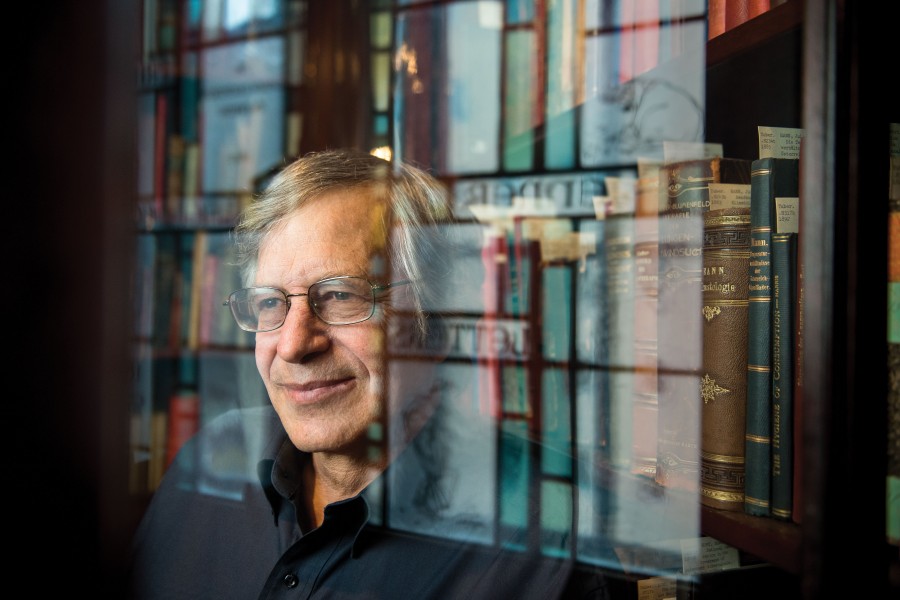

At least, that is the story told in Daniel Todes' sweeping Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science, just published by Oxford University Press. Todes, a professor in the School of Medicine's Depart?ment of the History of Medicine, spent more than 20 years sifting through thousands of pages in 27 different archives as he sought to understand the man he encountered in the scientific documenta?tion. What he found produced a life that diverges strikingly from both the Soviet and the Western accounting of the man and the science.

Pavlov was an icon in the Soviet Union. As such, he could only be written about in ways that conformed to the Soviet view of him as a brilliant experimentalist who observed facts and followed the logic of science-produced theories from those facts.

This version of Pavlov was the only one Todes knew before he first read some of the scientist's papers in the archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences during a 1990–91 research fellowship in St. Petersburg. Pavlov had a long career. He began working in the 1880s in the labs of German anatomist Carl Ludwig in Leipzig and physiolo?gist Rudolf Heidenhain in Breslau before land?ing a position in the Division of Physiology at the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St. Peters?burg. He led labs there for 45 years until his death at 86 in 1936. He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1904 for his work with digestive physiology and spent the last three decades of his life using his famous conditional reflex experimental pro?tocols to investigate the psyche of dogs as a way to understand the subjective human experience.

Such a career produced a mammoth amount of archival material. "I was not particularly attracted to what I at first knew of Pavlov as a man, this flinty objectivist," Todes says, adding that when he first understood the immensity of Pavlov's archival record, it kept him up at night. "The material, because he was a hero, had been collected over time and was just staggering. I think it's been decades since someone really sat down with all of Pavlov's works and just read them closely. If you do, you see immediately that [his science] isn't just a matter of compiling facts or good experimental technique. There's all that human stuff in there."

Todes was the right man in the right place to explore "all that human stuff." As a historian of science, he is deeply fascinated by metaphor. "If you or I are trying to think about something new, there's no way we can think about it except by drawing on things we think we know already," he says. "We do that in the form of metaphors, which we draw from all elements of our experi?ence. These metaphors structure scientific thought." He continues, "That, to me, is the greatest drama in the history of science. I'm basically a realist. I believe that there's an objec?tive reality independent of our consciousness. I don't think science is just a matter of opinion. But it's a deeply human endeavor, and reality being infinite, there's an infinite number of ways into it. Metaphors define paths into this reality— the questions that are asked and aren't asked."

Ever since his first visit in 1976–77 on an exchange program organized by the Interna?tional Research and Exchanges Board, Todes has been smitten by Russia, its people, its history, and its culture. Yes, he was from one of the kapitalisticheskie strany—the capitalist countries— but Russia felt like a second home. So he was uniquely positioned to meld his interest in meta?phor with an understanding of and sensitivity to Russian culture. In his first book, Darwin Without Malthus: The Struggle for Existence in Russian Evo?lutionary Thought (Oxford University Press, 1989), Todes explored how Russian evolutionists objected to the metaphors used by Darwin. Those metaphors had been informed by Thomas Robert Malthus' political economy and its indus?trial struggle for existence, which were anathema to the more communal-minded Russians.

When Todes started researching Pavlov in the early 1990s, it was around the time that former President Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost reform polices opened the Soviet Union to market economics and intellectual transpar?ency. In addition to Pavlov's scientific archives, Todes gained access to his correspondence. He found reports from the Communists who worked in Pavlov's labs and reported to their Party cells. He went to Russia so often he earned the trust of Russian archivists who shared their Pavlov notes and research with him. He met with Pavlov's granddaughters and great-granddaughters. "The material was so overwhelming, I realized I'm never going to have a better topic than this," Todes says. "So I wanted to do it right and I didn't want to hurry it. I thought this was a story that people might read, not just historians like me. It's the great Russian epic. It starts before the serfs are emancipated and it ends in Stalin's Russia. It's got art, it's got Dostoevsky, it's got the church. What else do you want?"

Todes took all the information he had gath?ered during roughly 20 years of research and turned it into a compelling 880-page biography that pays Pavlov one of the finer compliments a historian can: He turns an icon into a man. He has written that man's story as a sweeping drama where the scientist and the man are indivisible. "My dad used to tell me, 'Dan, work as hard as you can but if you ever have to choose between luck and skill, take luck,'" Todes jokes. "I was just really lucky."

Tell me—did you like Pavlov?" This is the first thing the spry, gray-haired Todes asks me before our first con?versation. His office is a compact room on the third floor of the Johns Hopkins Welch Medical Library. Uncluttered bookshelves line one wall, a small table with a computer atop it sits in a corner, and a wood chair faces an impressively tidy desk. Before he fields a single question, he wants to know my impression of Pavlov as rendered in his book.

I didn't dislike Pavlov. He seems like a bit of a hardass, at times overbearing, definitely confi?dent and bordering on the overly so—but all of this was directed at taking his work seriously. He seemed passionate about science and assured in his own ideas, but only if the experimental data supported them. He was willing to be proven incorrect or devise new experiments and variables when the data wasn't coming out as predicted. That's what a scientist is supposed to do, isn't it?

"My orientation toward history was always biographical," Todes says, pointing out that exploring history through one person's story succinctly provides a main character in a drama. "And for this question I'm most interested in— why scientists believe what they believe—if you take an individual, you can look into all their contexts: the personality, beliefs, teachers."

In Pavlov's case, those contexts are elaborate. His career started before the Bolshevik Revolu?tion and ended in the time of Josef Stalin, and how he has been regarded has changed. Todes notes that before perestroika, Pavlov was the great Soviet scientist whose objectivity led him to embrace Communism. In the 1990s, Pavlov became a dissident who fought the Communists tooth and nail. Neither is entirely accurate.

In America, Pavlov's science is improperly understood. His work with conditional reflex is misunderstood as having trained dogs to drool at the sound of a bell. Though Pavlov did document the amount of saliva dogs produced when they associated a stimulus with feeding, Todes notes that over three decades of research and tens of thousands of experiments, Pavlov and his co-workers used a bell in "rare, unimportant circum?stances." For Pavlov, a bell wasn't a suitable exper?imental protocol because it couldn't be precisely controlled. He primarily used a metronome, har?monium, buzzer, and electric shock device.

He also wasn't interested in "training" a dog to do anything. Conditional reflex, for Pavlov, became an experimental method to investigate his real objective: the subjective experience of the dog as a model for understanding the same in humans. And casting Pavlov as a scientist interested in any kind of subjective life is radi?cally at odds with how his conditional reflex experiments have been understood and por?trayed by the American behaviorist school of psychology, which believed the "behavior of animals can be investigated without appeal to consciousness," as John Watson wrote in his 1913 paper "Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It." Watson viewed Pavlov's conditional reflex experiments as a matter of external control— that an animal could be "conditioned" to respond in a specific manner whenever con?fronted with a specific external stimulus. This reading appears in a 1929 article in Time maga?zine about a physiological conference Pavlov attended in Cambridge, Massachusetts: "Behav?iorists have taken up his theories and made them fairly common knowledge. His picture of mental activity is mechanistic." The misunderstanding is perpetuated by scientists who took what they wanted from Pavlov's work and modeled research on that. Psychologist Howard Scott Liddell heard a lecture by a former Pavlov assistant at Cornell University in 1923 and designed his own behavior experiments based on it. In 1928, The New York Times covered a talk Liddell gave at the Society of Clinical Psychiatry at the Academy of Medicine where he said, "The result of this mechanical view of behavior is that all behavior can be ana?lyzed into reflexes, a reflex being the response of the animal to a change of environment which involves the nervous system." He adds, "Even the most complicated behavior can be shown to occur invariably according to laws which can be formulated definitely."

Today, "Pavlovian" still conveys the notion of an involuntary response, and these inaccurate assumptions initially permeated Todes' under?standing of Pavlov. "Looking back, it took me an amazingly long time to change the view of Pavlov that I brought with me to my research," Todes says. "I began with this general notion of Pavlov as a hardheaded objectivist, the just-the-facts guy, trying to reduce the psyche and explain it totally in terms of physiological phenomena."

Pavlov himself changed Todes' mind. While reading Pavlov's public speeches for both lay and scientific audiences and his personal correspon?dence, Todes found Pavlov using anthropomor?phic language when talking about the dogs in his experiments. How could a scientist with such a mechanistic view of the human mind believe dogs were displaying emotional states indepen?dent of the experimental protocol?

The more Todes researched, the more he started to notice expressions and ideas that con?flicted with Pavlov as the just-the-facts objectiv?ist. Examining lab notebooks, he'd come across descriptions of the dogs' personalities—greedy, nervous, lazy, a hero, a coward. These descrip?tions were even in his digestive research, which produced a detailed physiology of the digestive system in dogs and the regulatory role of the ner?vous system. Todes came across a speech Pavlov made wherein he talked about visiting the St. Petersburg zoo and feeling as if he'd come across all the characters in Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls. Pavlov routinely used such metaphoric language when talking about the dogs in his labs, meta?phors that appeared throughout his co-workers and assistants' research, writing, and lab notes.

Todes says that around the year 2000, he real?ized that the "greedy," "lazy," etc., personality traits that appeared as observations in the diges?tive research notes became the investigative tar?get of his conditional reflex experiments. Pavlov didn't have a mechanistic view of the mind. Pav?lov was trying to use conditional reflex as an experimental protocol to understand conscious?ness. He pursued this for 33 years, stopping only with his death in 1936 at 86. "That's when I real?ized what the behaviorists had done in America," Todes says. "They were saying, 'We can't deal with [the psyche] in a scientific psychology. We just deal with behaviors as external movements.' They were interpreting Pavlov through their lens and taking the parts of Pavlov that fit."

Pavlov disagreed categorically with this behav?iorist assumption. "Pavlov looked at behaviorism and said it reflected the pragmatic American point of view—that, generalizing unfairly, Ameri?cans as a pragmatic people, they're interested in what people do, not in what they're thinking," Todes says. "But he was a Russian through and through. He suffered over Dostoevsky and he was interested in the torments of our consciousness and what we could do about them. And you can't deal with that by defining it as unscientific. For him, the subjective experience was what science should be about."

Like Pavlov zeroing in on conditional reflex as a way to understand the psyche, Todes homed in on what the scientist revealed of himself in his writings. He found what he was look?ing for in Pavlov's private correspondence with his future wife, Serafima Vasil'evna Karchevskaia. In 1880, Karchevskaia helped organize a benefit for needy students at the women's gymnasium she attended in St. Petersburg. Fyodor Dostoevsky and Ivan Turgenev attended. Todes notes that Karchevskaia, six years younger than Pavlov, had missed the intellectual surge of 1860s reform-era Russia and retained her Orthodox faith. Dosto?evsky, who in novels such as The Adolescent (1875) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880) explored the spiritual conflicts between the "old" Russia and the modernizing ideas emerging in the 1860s, pro?vided a path for holding on to traditional faith and Russian values in the face of ostensible pro?gressivism. He made a huge impression on her— she referred to him as "the Prophet" in her unpublished memoir. And in a series of letters to Karchevskaia, Pavlov confesses to her that what religion does for her, science's search for truth does for him. It "is for me a kind of God, before whom I reveal everything, before whom I discard wretched worldly vanity," he wrote. "I always think to base my virtue, my pride, upon the attempt, the wish for truth, even if I cannot attain it."

Todes quite exhaustively shows how Pavlov pursued that unattainable goal. It's why Todes spent so much time parsing his reports and assistants' papers, getting to know the dogs as well as Pavlov's co-workers, closely reading his speeches and letters. The everyday micro-obser?vations of the man inform this macroscopic bio?graphical portrait. "You can read so much of this man and his culture in his science," Todes says of Pavlov. "It's like everything we produce. The sugar we eat is the result of a long and not always pretty social historical process that links us with people and children and other lands. Science is the same. It's not just the frozen facts at the end. It's a fascinating product of human activity that bears the marks of its creators."

Todes charts that human drama at the core of Pavlov's life and science in his book, but though it's written for a general audience, he realizes not everybody is going to pick up an 880-page volume. That's why he's teamed up with John Mann, a professor in the Johns Hopkins Film and Media Studies Program, and Sergei Krasikov, a New York–based Russian producer, to work on a documentary film. "About a year ago, we started this wonderful process where we decided to do a film based on Pavlov's quest, this search for order in a tumultuous, uncertain world," Todes says. "We want to use re-creations and archival films from Pavlov's work to focus on the man and his quest in a different way. Pavlov's great-granddaughter is thoroughly behind it. We have a narrative, we have a treatment, we have a team ready to go. All we need is the money for a trailer so we can apply for production funds."

In talking about what they have in mind, he mentions Particle Fever, the 2013 documentary about experiments at the Large Hadron Collider that led to confirmation of the Higgs boson. "What I loved about that film was that the real hero was the scientists' passion and the prob?lems of scientific inquiry," Todes says. "That's what we want. We have in mind something that both captures the sweep of his life and takes that problem of the quest into the science."

Particle profoundly benefited from being pro?duced and shepherded for roughly seven years by Johns Hopkins professor of physics and astronomy David Kaplan, who brought his knowledge of the field and its main figures to the project, presenting an intimate understanding of the scientists' minds. Todes had to find his way inside Pavlov's mind the old-fashioned way: primary research, and the effort comes through in his book and discussion about the man he once regarded as a flinty objectivist.

"You've got to get into the nitty-gritty—the protocols, the dogs, the data, how he crunched his data—and that's what I did," Todes says. "In that nitty-gritty you can see Pavlov's personality, the overall quest as he's working on it and con?fronting problems. You can empathize with him."

Toward the end of the book, Todes includes a translation of a few comments Pavlov made to his lab staff on December 27, 1926, which were jotted down in shorthand by one of his co-work?ers. The occasion was the impending publication of his conditional reflex monograph. At this point he had been working on it for 25 years:

I am unfortunately burdened by nature with two qualities. Perhaps they are objectively good, but one of them is very burdensome for me. On the one hand, I am enthusiastic and surrender myself to my work with great passion; but together with this I am always weighed down by doubts. The smallest obstacle disturbs my balance and I am tortured until I find an explanation, until new facts bring me again into balance.

I must thank you for all your work, for the mass of collected facts—for having superbly subdued this beast of doubt. And now, when the book is appearing in which I give the conclusions of our 25 years of work—now, I hope, this beast will retreat from me. And my greatest gratitude for liberating me from torment is to you.

Here's a man at 77, a Nobel Prize–winning giant in his field, confiding to his employees that even he questioned himself during their work together. It's a remarkably candid moment and a reminder of the touching vulnerability that makes man the doubting beast: Even the great icon who spent his entire life searching for answers worries that what he's chasing is going to remain forever just out of reach.

"This is just such a human feeling," Todes says. "I enjoyed following that tension, this quest, this great scientist in the muck. And I learned it's very complicated but that you can see the contin?ual interpenetration of experimental data and val?ues and personality on all these levels. Even at the end of his life, he's changing his mind, recasting it, thinking that maybe now if he differentiates between conditional reflexes and associations it'll all click. To me, it's just such a touching drama."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Science+Technology