A randy 18th-century gent first introduced Mary Fissell, a professor in the School of Medicine's Department of the History of Medicine, to her current obsession. In the 1980s she went to the Somerset record office in southwest Britain while conducting her dissertation research into the lives of ordinary patients in the 18th century. She did not find exactly what she was looking for, but she did come across the writings of a local excise officer and tax guide from the time period. "He was a love 'em and leave 'em kind of guy, and he wrote the most incredible memoir," Fissell says. "He actually describes being taught to masturbate." He also talked about stealing his mother's copy of Aristotle's Masterpiece "because he wanted to know what women looked like underneath their clothes," Fissell says. "That was the first time I met the book, really."

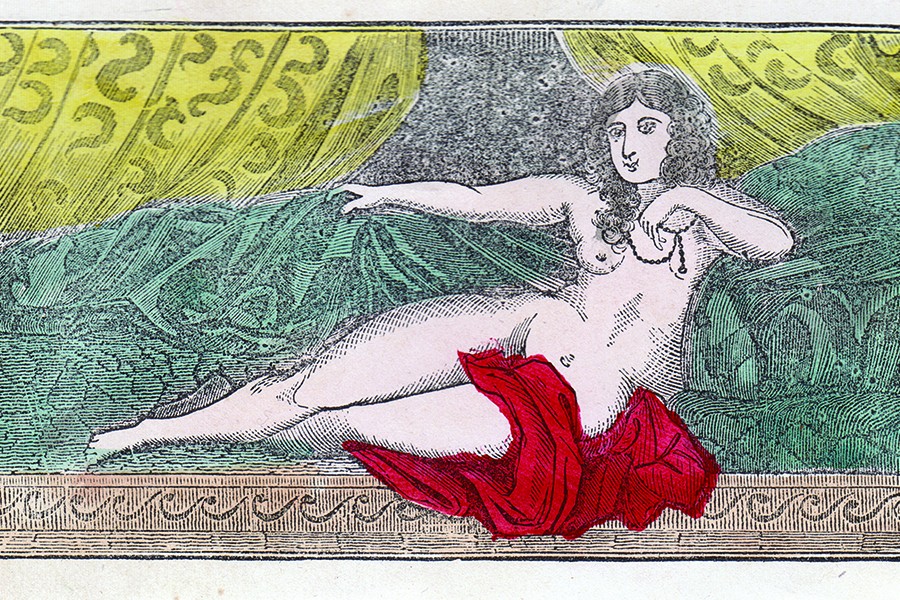

Capitalizing on the Greek philosopher's reputation as a sex expert in England at the time, Aristotle's Masterpiece was first published in 1684, and it was written neither by nor about Aristotle. It is a sex and pregnancy manual, offering male and female anatomical descriptions, as well as information about sexual intercourse, reproduction, and childbirth. It remained in print, from a number of different publishers, from the late 17th century into the 20th century, by which point it was a risqué sex book found well used. In James Joyce's Ulysses, Leopold Bloom comes across it on a Dublin hawker's cart: "Mr Bloom turned over idly pages of The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, then of Aristotle's Masterpiece. Crooked botched print. Plates: infants cuddled in a ball in bloodred wombs like livers of slaughtered cows."

The longevity of Aristotle's Masterpiece interests Fissell; it offers a window into understanding what common people knew about their bodies—a vernacular knowledge of medicine. "If your great-great or great-great-great grandmother lived in the Anglo-American world and had a book on sex tucked up in her sock drawer, this is it," she says. "That's really exciting to me. I'll never get what one woman said to another in the birthing room. But I can get closer to that by looking at the books that are really successful because they're offering something that their readers want."

Over the past decade Fissell (with assistance from Christine Ruggere, the curator of the historical collection in Johns Hopkins' Institute of the History of Medicine's library) has collected more than 50 copies of Masterpiece, from 1684 into the 20th century. It is roughly the size of a pulp paperback, and Fissell says it was just as easy to find in secondhand shops. By hunting down so many different editions, she can get a sense of how wide the book's information spread. Copies with owners' inscriptions provide markers of where and when the book was read, and by going through other documents (correspondence, newspaper ads, oral histories, etc.) Fissell is gaining an appreciation of what its readers learned from it and developing theories of why it persisted for so long.

One idea she has is that Masterpiece's positive view of sexuality was appealing to women in the 19th century, a period noted for the Victorian era's more corseted sexuality, morality campaigns, and anti-masturbation panic. "I think it provides an alternate discourse, especially in the 19th century, because it valorizes female sexual pleasure," Fissell says. "It always says that women are supposed to have orgasm, that it's a good thing, that that's how babies get made. And it has pretty lush descriptions of how great sex is, for the time."

In this regard, Masterpiece is like Marie Stopes' 1918 book Married Love, which is what Fissell believes eventually displaced Masterpiece among working-class women (it talks about contraception; Masterpiece doesn't) or, more recently, Our Bodies, Ourselves. These texts discussed things that were not talked about openly. Today, it is easy to look back at what people thought they knew about the body and health and snicker at everything they did not know, but as Fissell points out, people were not fools. They made medical decisions and were often quite pleased with the outcomes and quality of care they received. So they were making decisions based on something.

"I wanted to give agency to the patients, to say that even though they may have had crappy choices, they made them, and the aggregate of those choices shaped an emergent health care system," Fissell says. "I'm still interested in how ordinary people understand their bodies in the natural world because I think that's really powerful. And those understandings are profoundly driven by culture, economics, politics, et cetera."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged history of medicine, mary fissell, sex education